Subtotal: 1.303,05€ (incl. VAT)

These scientists live like astronauts without leaving Earth

This article was originally published on Undark. Read the original article.

In January 2023, Tara Sweeney’s plane landed on Thwaites Glacier, a 74,000-square-mile mass of frozen water in West Antarctica. She arrived with an international research team to study the glacier’s geology and ice fabric, and how its ice melt might contribute to sea level rise. But while near Earth’s southernmost point, Sweeney kept thinking about the moon.

“It felt every bit of what I think it will feel like being a space explorer,” says Sweeney, a former Air Force officer who’s now working on a doctorate in lunar geology at the University of Texas at El Paso. “You have all of these resources, and you get to be the one to go out and do the exploring and do the science. And that was really spectacular.”

That similarity is why space scientists study the physiology and psychology of people living in Antarctic and other remote outposts: For around 25 years, people have played out what existence might be like on, or en route to, another world. Polar explorers are, in a way, analogous to astronauts who land on alien planets. And while Sweeney wasn’t technically on an “analog astronaut” mission—her primary objective being the geological exploration of Earth—her days played out much the same as a space explorer’s might.

For 16 days, Sweeney and her colleagues lived in tents on the ice, spending half their time trapped inside as storms blew snow against their tents. When the weather permitted, Sweeney snowmobiled to and from seismometer sites, once getting caught in a whiteout that, she says, felt like zooming inside a ping-pong ball.

On the glacier, Sweeney was always cold, sometimes bored, often frustrated. But she was also alive, elated. And she felt a form of focus that eluded her on her home continent. “I had three objectives: to be a good crewmate, to do good science, and to stay alive,” she says. “That’s all I had to do.”

None of that was easy, of course. But it may have been easier than landing back on the earth of El Paso. “My mission ended, and it’s over,” she says. “And how do I process through all these things that I’m feeling?”

Then, in May, she attended the 2023 Analog Astronaut Conference, a gathering of people who simulate long-term space travel from the relative safety and comfort of Earth. Sweeney had learned about the event when she visited an analog facility in the country of Jordan. There, she’d met one of the conference’s founders, Jas Purewal, who invited her to the gathering.

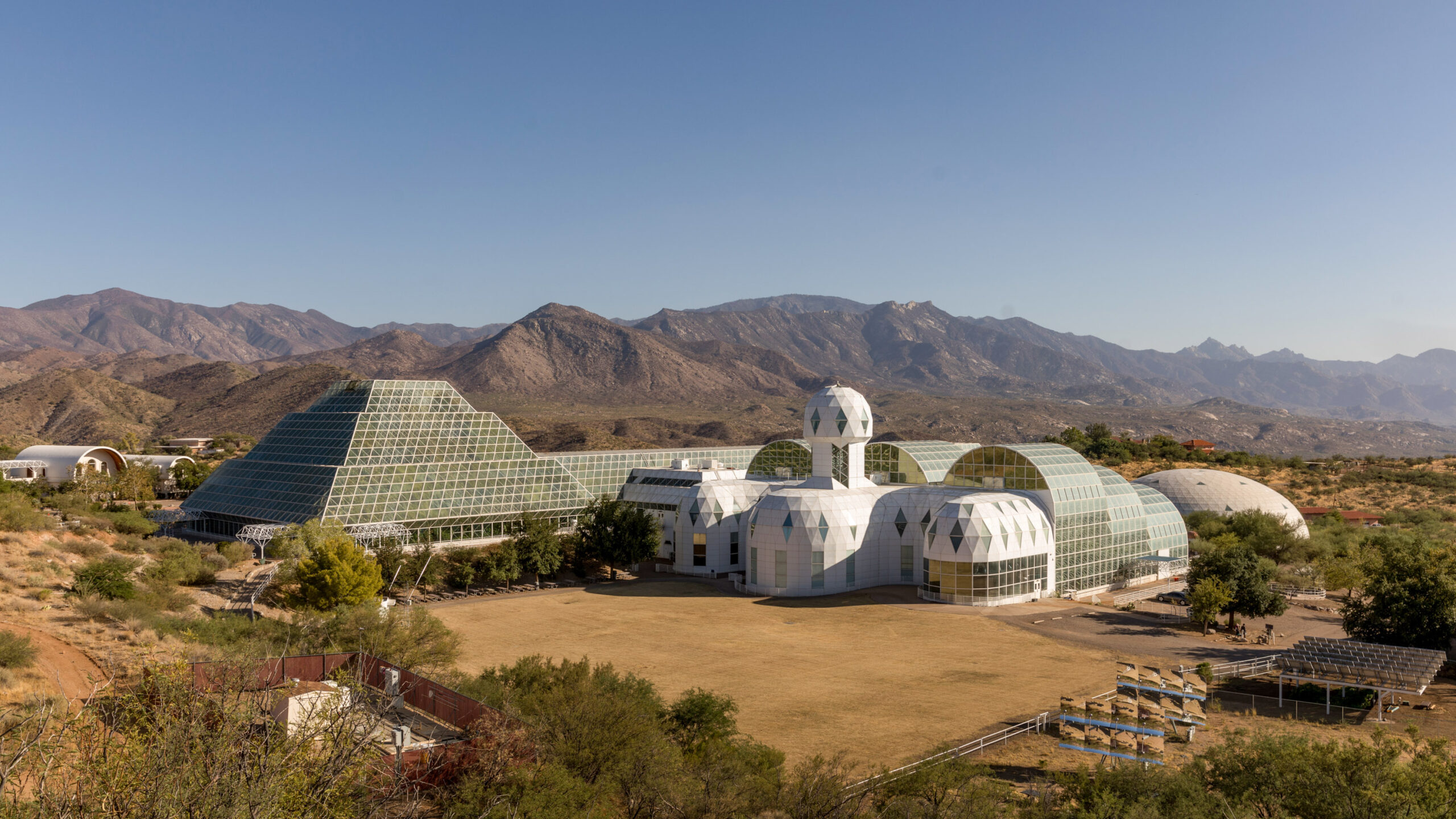

The meeting was held, appropriately, at Biosphere 2, a glass-paneled, self-contained habitat in the Arizona desert that resembles a 1980s sci-fi vision of a space settlement—one of the first facilities built, in part, to understand whether humans could create a habitable environment on a hostile planet.

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

A speaker at the conference had spent eight months locked inside a simulated space habitat in Moscow, Russia, and she talked about how the post-mission period had been hard for her. The psychological toll of reintegration became a chattering theme throughout the whole meeting. Sweeney, it turned out, wasn’t alone.

Across the world, around 20 analog space facilities host people who volunteer to be study subjects, isolating themselves for weeks or months in polar stations, desert outposts, or even sealed habitats inside NASA centers. These places are intended to mimic how people might fare on Mars or the moon, or on long-term orbital stations. Such research, scientists say, can help test out medical and software tools, enhance indoor agriculture, and address the difficulties analog astronauts face, including, like Sweeney’s, those that come when their “missions” are over.

Lately, a community of researchers has started to make the field more formalized: laying out standards so that results are comparable; gathering research papers into a single database so investigators can build on previous work; and bringing scientists, participants, and facility directors together to share results and insights.

With that cohesion, a formerly quiet area of research is enhancing its reputation and looking to gain more credibility with space agencies. “I think the analogs are underestimated,” says Jenni Hesterman, a retired Air Force officer who is helping spearhead this formalization. “A lot of people think it’s just space camp.”

Analog astronaut facilities emerged as a way to test-drive space missions without the price tag of actually going to space. Scientists, for example, want to make sure tools work properly, and so analog astronauts will test out equipment ranging from spacesuits to extreme-environment medical equipment.

Researchers are also interested in how astronauts fare in isolation, and so they will sometimes track characteristics like microbiome changes, stress levels, and immune responses by taking samples of spit, skin, blood, urine, and fecal matter. Analog missions “can give us insights about how a person would react or what kind of team—what kind of mix of people—can react to some challenges,” says Francesco Pagnini, a psychology professor at the Catholic University of Sacred Heart in Italy, who has researched human behavior and performance in collaboration with the European and Italian space agencies.

Some facilities are run by space agencies, like NASA’s Human Exploration Research Analog, or HERA, which is located inside NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. The center also houses a 3D-printed habitat called Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog, or CHAPEA, where crews will simulate a year-long mission to Mars. The structure looks like what would happen if an artificial intelligence created a cosmic living space using IKEA as its source material.

“My mission ended, and it’s over,” Sweeney says. “And how do I process through all these things that I’m feeling?”

Most analog spots, though, are run by private organizations and take research proposals from space agencies, university researchers, and sometimes laypeople with projects that the facilities select through an application process.

Such work has been going on for decades: NASA’s first official analog mission took place in 1997, in Death Valley, when four people spent a week pretending to be Martian geologists. In 2000, the nonprofit Mars Society, a space-exploration advocacy and research organization, built the Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station in Nunavut, Canada, and soon after constructed the Mars Desert Research Station in Utah. (Both facilities have been used by NASA researchers, too.) But the practice was in place long before those projects, even if the terminology and permanent facilities were not: in the Apollo era, astronauts used to try out their rovers and space walks, along with scientific techniques, in Arizona and Hawaii.

Every day on “Mars,” Purewal and Hesterman’s team completed a set of missions, including simulated spacewalks.

Many facilities, according to Ronita Cromwell, formerly the lead scientist of NASA’s Flight Analogs Project, are located in two types of places: extreme environments or controlled ones. The former include Antarctic or Arctic research stations, which tend to be used to study topics like sleep patterns and team dynamics. The latter—sealed, simulated habitats—are primarily useful for human behavior research, like learning how cognitive ability changes over the course of a mission, or testing out equipment, like software that helps astronauts make decisions without communicating to mission control. That independence becomes necessary as crews travel farther from Earth, because the communication delays increase with distance.

During her work on NASA’s mission simulations, Cromwell saw their value. “What excited me is that we were able to create sort of spaceflight situations on the ground, to study spaceflight changes in the human body,” Cromwell says, “whether they be, you know, psychological, cognitive changes, or physiological changes.”

Psychiatry researchers from the University of Pennsylvania, for instance, recently found that members of a crew at HERA performed better on cognition tasks—like clicking on squares that randomly appear on a screen and memorizing three-dimensional objects—as their mission went on. Another recent HERA study, led by scientists at Northwestern and DePaul, found that over time, teams got better at executing physical tasks together, but worsened when they tried to work together creatively and intellectually on tasks like brainstorming as many uses as possible for a given object. Those brain and behavioral changes could teach scientists about tight teams deployed in other remote, tedious, stressful situations. “I think space psychology can also speak a lot about everyday life,” says Pagnini.

On the physical side, an international team that included a NASA scientist recently used the Mars Desert Research Station to test whether analog astronauts could be quickly taught how to fix broken bones using a device that could work on Mars—or an earthly site far from medical facilities. Investigations into self-contained, sustainable living reveal how low-resource existence could work on Earth, too. For example, another crew, led by Griffith University medical researchers, performed an experiment extracting water from minerals in case of emergency.

While scientific research that actually takes place in space usually gets the spotlight, the ground-testing of all systems, including human ones, is necessary, if not always glamorous or publicly lauded. “I felt like I was in charge of a deep, dark secret,” says Cromwell, jokingly, of her work on the NASA analog program.

In fact, even people who work in adjacent fields sometimes haven’t heard of the field. Purewal, an astrophysicist, only learned about analog space research in 2020. With covid-19 restrictions in place, though, most facilities had halted new missions. “If I can’t go to an analog, maybe I can bring the analog to me,” Purewal thought.

Amid the drapey willow branches and manicured hedges of her parents’ backyard in Warwick, England, she constructed a geodesic dome out of broomstick handles and tent-like materials. Purewal sequestered inside for a week, leaving only to use the bathroom—and then only while wearing a simulated spacesuit. She communicated with those outside her dome on a synthesized 20-minute delay and ate freeze-dried foods, which she came to hate, and insect protein from mealworms and locusts, which she came to like more than she anticipated.

While Purewal admits her personal analog was “low-fidelity,” it offered a test drive for more rigorous research. By 2021, Purewal had, with SpaceX civilian astronaut Sian Proctor, cofounded the Analog Astronaut Conference that Sweeney attended, along with an associated online community of more than 1,000 people. She also participated in an analog mission in someone else’s backyard—one surrounded by Utah State Trust Lands—in November 2022. Their endeavor was sponsored by the Mars Society and involved research on mental health, geologic research tools, and sustainable food supplies, all of which would be necessary if they were going to Mars.

But they weren’t headed to Mars; they were headed to Utah. About five minutes from the small town of Hanksville—home to “Hollow Mountain,” a gas station convenience store dug out of a rock formation—sits the turnoff to the Mars Desert Research Station. Operated by the Mars Society, the facility is 3.4 miles down a dirt track called N Cow Dung Road. The landscape looks otherworldly: mushroom-shaped rock formations; sandy, granular ground; and eroded hills of red rock.

BILL STAFFORD/NASA

The station sits in a flat spot surrounded by those hills, with a cylindrical living space two stories tall but just 26 feet in diameter. The habitat links out via above-ground “tunnels” to a greenhouse and a geodesic dome that resembles Purewal’s initial backyard creation, and houses a control center and lab.

In November 2022, Purewal brought a team there for two weeks, with Hesterman as commander. In the habitat, an astrobiology student tried to grow edible mushrooms in the crew’s food waste. Another team member wanted to see if they could make yogurt from powdered milk and bacteria. Purewal, meanwhile, was experimenting with an AI companion robot called PARO. Shaped like a baby harp seal, PARO is typically used to relieve stress in medical situations. The crew members interacted with PARO and wore bio-monitoring straps that measured things like heart rate as they did so.

After their mission ended, they spoke with others, and heard about issues such as expired fire extinguishers, or the lack of safety training for participants who would be using specialized technologies and life support systems. They consulted Emily Apollonio, a former aircraft accident investigator. In 2022, she traveled to Hawaii to live at HI-SEAS, a 1,200-square-foot analog station located 8,200 feet above sea level on the Mauna Loa volcano. Apollonio thought HI-SEAS had avoidable problems. For one, the bathroom had only a composting toilet, which the mission crew weren’t allowed to pee in, and a urinal, which the women had to use too.

With a draft version released this June, they hope to improve conditions for participants—ensuring, for instance, that facilities adhere to building codes and provide adequate medical support. They also want to encourage analog participants to follow research best practices to ensure rigorous outputs. The standards suggest, for instance, that each mission have its research plan pre-validated by the principal investigator and habitat director, a timeline for research completion, and an Institutional Review Board approval in place for human experiments. While projects with federal or institutional grant funding go through these steps anyway, the formality isn’t uniform across the board.

NASA

While some analogs already have rigorous protocols in place to protect participants, the safety issues and inclusivity gaps she heard about from colleagues helped inspire Apollonio to start a training and consulting company called Interstellar Performance Labs to help prepare would-be analog astronauts before their missions. She also started to work with Purewal, Hesterman, and others on a document called “International Guidelines and Standards for Space Analogs.”

The standards also detail the creation of a research database, putting all the write-ups (peer-reviewed and otherwise) of analog projects in one place. That way, people aren’t duplicating efforts—as the mushroom grower, it turns out, was—unless they mean to test the replicability of results. They can also better link their studies to space agencies’ established needs to be more directly helpful and relevant to the real world.

“I didn’t know where to look, I didn’t know where to go,” Apollonio says. “I couldn’t hear my thoughts.”

As part of this centralization effort, Purewal, Apollonio, Hesterman, and colleagues are also putting together what they call the World’s Biggest Analog: a simultaneous, month-long mission involving at least 10 isolated bases across the world, which together will simulate a large, cooperative future presence in space.

So far, though, attempts to give the community cohesion and coherency have yet to fully address the aspect of analog life that gives many participants trouble: the end of their mission. “Being in an analog mission was less difficult than coming out an analog mission,” says Apollonio, of her own experience.

Shortly after emerging from HI-SEAS, she walked around the streets of Waikiki with her husband. The lights, the noise—everything was too much. “I didn’t know where to look, I didn’t know where to go,” she says. “I couldn’t hear my thoughts.” After they chose a restaurant for dinner, and the server handed her a menu, she froze. “I have to choose my own food,” she realized. It was overwhelming, and that feeling didn’t abate.

Meanwhile, few other people understood the experience, says Hesterman. “You come home and you’re all excited, like, you want to tell everybody about it,” she continues. “You tell everybody about it once, and then they’re just done. On back to paying the bills and cutting the grass and stuff. You still want to talk about it.”

Purewal missed the team and the sense of shared purpose, and started to seek it outside the simulation. “I need to find this same feeling in my day-to-day life,” she says. “We all kind of need our crew.”

Research on the post-mission experience is scant, says Pagnini. In March 2023, he coauthored a review paper, commissioned by the European Space Agency, which aimed to lay out the state of research on human behavior and performance in space, including gaps in the science. Studying how astronauts react and cope “post-mission,” his research found, has been particularly neglected. The same is true of returning from analog space.

Pagnini says the research isn’t just relevant to analog or actual astronauts. Life in space has similarities to life on Earth—including in its difficulties. Italy’s heavily restrictive and prolonged covid-19 lockdown, for instance, resembled going away on a mission. “When we got out of the lockdown phase, getting in touch with other people was kind of strange,” he says. Much of living a regular life on Earth was strange.

NASA

The strangeness also characterizes other experiences, like military deployments and the subsequent return to domestic life. “The expectation is kind of that families will live happily ever after” once they’re reunited, says Leanne Knobloch, a professor of communication at the University of Illinois, who performed a large reintegration study on military couples. “So that’s why reintegration has sometimes been overlooked, but more and more researchers are starting to recognize that it is a challenging period, and it’s not the storybook ending that people make it out to be.”

THE MARS SOCIETY

Knobloch’s work includes suggestions for easing the transition, such as preparing people for the issues they’re likely to experience. “If you’re ready and expect that you might experience some of these problems, it won’t be so stressful,” she says. “Because you’ll recognize that they’re normal.”

Apollonio’s Interstellar Performance Labs, for one, is already planning to include education on “aftercare,” educating people about what she calls the “deorbiting effect” of returning to regular life.

When the day finally came for Sweeney to depart Thwaites Glacier, the aircraft seemed to materialize right out of the sky, as though the remote outpost had transformed into a busy airport. As she was leaving, she looked down at the camp where half her team remained. “You could just see how small our little footprint was,” she says. A speck in the middle of endless white space.

Since she landed in North America, Sweeney has savored time with her family. But the adjustment hasn’t been easy. “Each day that ticks by of being back, I started feeling pulled in different directions,” she says. With numerous projects ongoing—mentoring, speaking, doing her doctoral research—she felt her sense of self splintering. In Antarctica, she had been a smooth, singular whole.

But at the Analog Astronaut Conference in May, hearing about others’ similar readjustment difficulties, Sweeney felt some sense of normalcy. Having a community of support could help with post-mission struggles. Further research—aided by the new database and standardization measures—could help uncover best coping strategies, along with the keys to successful crew dynamics, stress creators and mitigators, and tools and designs that make the practicalities of a mission easier. Maybe someone will look at the database, see this scientific gap, and try to fill it.

Such research might resonate with Sweeney and others having trouble readjusting to their daily lives. “We have to get back to work, we have to go see our families, we want to pick up the projects we were doing before,” she says. “But also, we need to make space for the magnitude of the experience that we just had. And to be able to decompress from that.”