Will we ever trust robots?

The world might seem to be on the brink of a humanoid-robot heyday. New breakthroughs in artificial intelligence promise the type of capable, general-purpose robots previously seen only in science fiction—robots that can do things like assemble cars, care for patients, or tidy our homes, all without being given specialized instructions.

It’s an idea that has attracted an enormous amount of attention, capital, and optimism. Figure raised $675 million for its humanoid robot in 2024, less than two years after being founded. At a Tesla event this past October, the company’s Optimus robots outshined the self-driving taxi that was meant to be the star of the show. Tesla’s CEO, Elon Musk, believes that these robots could somehow build “a future where there is no poverty.” One might think that supremely capable humanoids are just a few years away from populating our homes, war zones, workplaces, borders, schools, and hospitals to serve roles as varied as therapists, carpenters, home health aides, and soldiers.

Yet recent progress has arguably been more about style than substance. Advancements in AI have undoubtedly made robots easier to train, but they have yet to enable them to truly sense their surroundings, “think” of what to do next, and carry out those decisions in the way some viral videos might imply. In many of these demonstrations (including Tesla’s), when a robot is pouring a drink or wiping down a counter, it is not acting autonomously, even if it appears to be. Instead, it is being controlled remotely by human operators, a technique roboticists refer to as teleoperation. The futuristic looks of such humanoids, which usually borrow from dystopian Hollywood sci-fi tropes like screens for faces, sharp eyes, and towering, metallic forms, suggest the robots are more capable than they often are.

“I’m worried that we’re at peak hype,” says Leila Takayama, a robotics expert and vice president of design and human-robot interaction at the warehouse robotics company Robust AI. “There’s a bit of an arms war—or humanoids war—between all the big tech companies to flex and show that they can do more and they can do better.” As a result, she says, any roboticist not working on a humanoid has to answer to investors as to why. “We have to talk about them now, and we didn’t have to a year ago,” Takayama told me.

Shariq Hashme, a former employee of both OpenAI and Scale AI, entered his robotics firm Prosper into this arms race in 2021. The company is developing a humanoid robot it calls Alfie to perform domestic tasks in homes, hospitals, and hotels. Prosper hopes to manufacture and sell Alfies for approximately $10,000 to $15,000 each.

“Why are we enamored with this idea of building a replica of ourselves?”

Guy Hoffman, associate professor, Cornell University

In conceiving the design for Alfie, Hashme identified trustworthiness as the factor that should trump all other considerations, and the top challenge that needs to be overcome to see humanoids benefit society. Hashme believes one essential tactic to get people to put their trust in Alfie is to build a detailed character from the ground up—something humanlike but not too human.

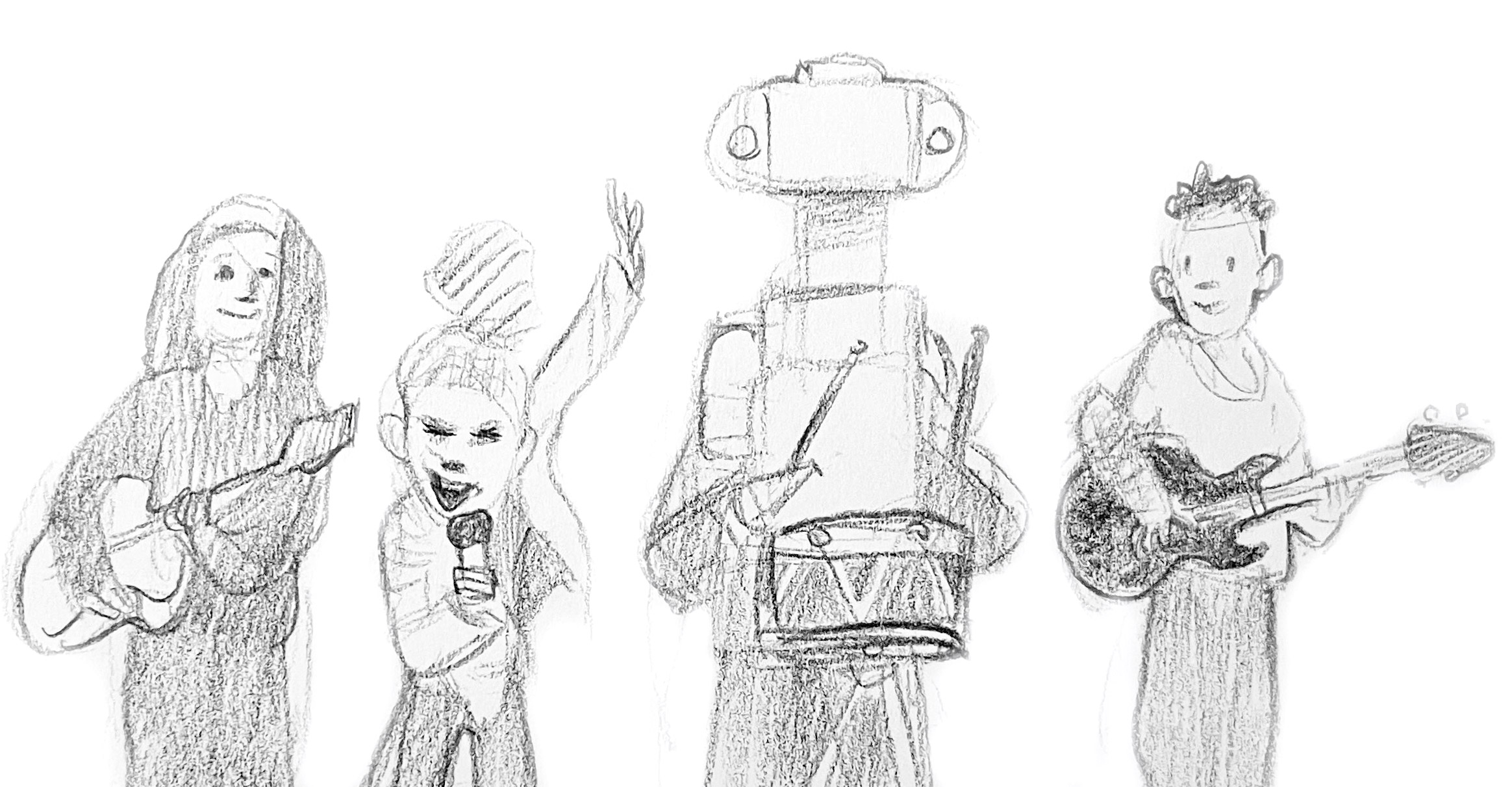

This is about more than just Alfie’s appearance. Hashme and his colleagues are envisioning the way the robot moves and signals what he’ll do next; imagining desires and flaws that shape his approach to tasks; and crafting an internal code of ethics that governs the instructions he will and will not accept from his owners.

In some ways, leaning so heavily on the principle of trustworthiness for Alfie feels premature; Prosper has raised a tiny amount of capital compared with giants like Tesla or Figure and is months (or years) away from shipping a product. But the need to tackle the issue of trustworthiness head-on and early reflects the messy moment humanoids are in: Despite all the investment and research, few people would feel warm and comfortable with such a robot if it walked into their living room right now. We’d wonder what data it was recording about us and our surroundings, fear it might someday take our job, or be turned off by its way of moving; rather than elegant and useful, humanoids are often cumbersome and creepy. Overcoming that lack of trust will be the first hurdle to clear before humanoids can live up to their hype.

But on the road to helping Alfie win our trust, one question looms larger than any other: How much will he be able to do on his own? How much will he still rely on humans?

New AI techniques have made it faster to train robots through demonstration data—usually some combination of images, videos, and other data created by humans doing tasks like washing dishes while wearing sensors that pick up on their movements. This data can then coach robots through those tasks much the way that a large body of text can help a large language model create sentences. Still, this method requires lots of data, and lots of humans need to step in and correct for errors.

Hashme told me that he expects the first release of Alfie to handle only about 20% of tasks on his own. The rest will be assisted by a Prosper team of “remote assistants,” at least some of them based in the Philippines, who will have the ability to remotely control Alfie’s movements. When I raised, among other concerns, whether it’s viable for a robotics business to rely on manual human labor for so many tasks, Hashme pointed to the successes of Scale AI. That company, which processes training data for AI applications, has a significant workforce in the Philippines—and is often criticized for its labor practices. Hashme was one of the people managing that workforce for about a year before founding Prosper. His departure from Scale AI was itself set off by a violation of trust—one for which he would serve time in federal prison.

The success or failure of Alfie will reveal much about society’s willingness to welcome humanoid robots into our private spaces. Can we accept a profoundly new and asymmetric labor arrangement in which workers in low-wage countries use robotic interfaces to perform physical tasks for us at home? Will we trust them to safeguard private data and images of us and our families? On the most basic level, will the robots even be useful?

To address some of these concerns around trust, Hashme brought in Buck Lewis. Two decades before Lewis worked with robots, before he was charged with designing a humanoid that people would trust rather than fear, the challenge in front of him was a rat.

In 2001, Lewis was a revered animator and one of the top minds at Pixar. His specialty was designing characters with deep, universal appeal, a top concern to studios that fund high-budget projects aimed at capturing audiences worldwide. It was a niche that had led Lewis to bring trucks and sedans to life in the movie Cars and create characters for many DreamWorks and Disney films. But when Jan Pinkava, the creative force behind Ratatouille, told Lewis about his pitch for that film—the story of a rat who wants to be a chef—the task felt insurmountable. Rats evoke such fear and apprehension in humans that their very name has become a shorthand for someone who cannot be trusted. How could Lewis turn a maligned rodent into an endearing chef? “It’s a deeply ingrained aversion, because rats are horrifying,” he told me. “For this to work, we had to create a character that rewires people’s perceptions.”

To do that, Lewis spent a lot of time in his head, imagining scenes like a group of rats hosting a playful pop-up dinner on a sidewalk in Paris. The result was Remy, a Parisian rat who not only rose through the culinary ranks in Ratatouille but was so lovable that demand for pet rats surged globally after the film’s release in 2007.

Two decades later, Lewis has made a career change and is now in charge of crafting every aspect of Alfie’s character at Prosper. Much as the appealing Remy rebranded rats, Alfie represents Lewis’s attempt to change the image of humanoid robots, from futuristic and dangerous to helpful and trustworthy.

Prosper’s approach reflects a foundational robotics concept articulated by Rodney Brooks, a founder of iRobot, which created the Roomba: “The visual appearance of a robot makes a promise about what it can do and how smart it is. It needs to deliver or slightly overdeliver on that promise or it will not be accepted.”

According to this principle, any humanoid robot makes the promise that it can behave like a human—which is an exceedingly high bar. So high, in fact, that some firms reject it. Some humanoid-skeptic roboticists doubt that a helpful robot needs to resemble a human at all when it could instead accomplish practical tasks without being anthropomorphized.

“Why are we enamored with this idea of building a replica of ourselves?” asks Guy Hoffman, a roboticist focused on human-robot interactions and an associate professor at Cornell University’s engineering school.

The chief argument for robots with human characteristics is a functional one: Our homes and workplaces were built by and for humans, so a robot with a humanlike form will navigate them more easily. But Hoffman believes there’s another reason: “Through this kind of humanoid design, we are selling a story about this robot that it is in some way equivalent to us or to the things that we can do.” In other words, build a robot that looks like a human, and people will assume it’s as capable as one.

In designing Alfie’s physical appearance, Prosper has borrowed some aspects of typical humanoid design but rejected others. Alfie has wheels instead of legs, for example, as bipedal robots are currently less stable in home environments, but he does have arms and a head. The robot will be built on a vertical column that resembles a torso; his specific height and weight are not yet public. He will have two emergency stop buttons.

Nothing about Alfie’s design will attempt to obscure the fact that he is a robot, Lewis says. “The antithesis [of trustworthiness] would be designing a robot that’s intended to emulate a human … and its measure of success is based on how well it has deceived you,” he told me. “Like, ‘Wow, I was talking to that thing for five minutes and I didn’t realize it’s a robot.’ That, to me, is dishonest.”

But much other humanoid innovation is headed in a direction where deception seems to be an increasingly attractive concept. In 2023, several ultrarealistic humanoid robots appeared in the crowd at an NFL game at SoFi stadium in California; after a video of them went viral, Disney revealed they were actually just people in suits, a stunt to promote a movie. Nine months later, researchers from the University of Tokyo unveiled a way to attach engineered skin, which used human cells, over the face of a robot in an attempt to more perfectly resemble a human face.

“Through this kind of humanoid design, we are selling a story [that this robot] is in some way equivalent to us or to the things that we can do.”

Guy Hoffman, roboticist

Lewis has considered much more than just Alfie’s appearance. He and Prosper envision Alfie as an ambassador from a future civilization in which robots have incorporated the best qualities of humanity. He’s not young or old but has the wisdom of middle age, and his primary function in life is to be of service to people on their terms. Like any compelling character, Alfie has flaws people can relate to—he wishes he could be faster, and he tends to be a bit obsessive about finishing the tasks asked of him. Core tenets of Alfie’s service are to respect boundaries, to be discreet and nonjudgmental, and to earn trust.

“He’s an entity that’s nonhuman, but he has a sort of sentience,” Lewis says. “I’m trying to avoid looking at it as directly comparable to human consciousness.”

I’ve been referring to Alfie as “he”—at the risk of over-anthropomorphizing what is currently a robot in development—because Lewis pictures him as a gendered male. When I asked why he pictures Alfie as having a gender, he said it’s probably a relic from the archetypal male butlers he saw on television shows like Batman growing up. But in a conversation with Hashme, I learned there is actually a real-life butler who is in some ways serving as an inspiration for Alfie.

That would be Fitzgerald Heslop. Heslop has decades of experience in high-end hospitality training, and for seven years he was the only person within the United States Department of Defense qualified to train household managers who would run the homes of three- and four-star generals. Heslop now runs the household of a wealthy family in the Middle East (he declined to get more specific) and has been contracted by Prosper to inform Alfie’s approach to service within the home.

Shortly into my conversation with Heslop, he elaborated on what excellent service looks like. “That’s the level of creativity the good butler deals in: the making of beautiful moments to put people at their ease and increase their pleasure,” he said, quoting Steven M. Ferry’s book Butlers & Household Managers: 21st Century Professionals. He spoke with conviction about the impact great service can have on the world and about how protocol and etiquette can level the egos of even top dignitaries. Citing a quote often attributed to Mahatma Gandhi, he said, “The best way to find yourself is to lose yourself in the service of others.”

Though he has no experience in robotics, Heslop is drawn to the idea that household robots could someday provide impeccable levels of service, and he thinks that Prosper has identified the right priorities to get there. “Privacy and discretion, attention to detail, and meticulous eyes for that are mission critical to the overall objective of the company,” he says. “And more importantly, in this case, Alfie.”

It is one thing to dream up an Alfie in sketchbooks, and another to build him. In the real world, the first version of Alfie will depend on remote assistants, mostly working abroad, to handle approximately 80% of its household tasks. These assistants will use interfaces not unlike video-game controllers to control Alfie’s movements, relying on data from his sensors and cameras to guide them in washing dishes or clearing a table.

Hashme says efforts are being made to conceal or anonymize personally revealing data while the robot is being teleoperated. That will include steps like removing sensitive objects and people’s faces from recordings and allowing users to delete any footage they like. Ideally, Hashme wrote in an email, Alfie “will often simply look away from any potentially private activities.”

The AI industry has an appalling track record when it comes to workers in low-wage countries performing the hidden labor required to build cutting-edge models. Workers in Kenya were reportedly paid less than $2 an hour to manually purge toxic training data, including content describing child sexual abuse and torture, for OpenAI. Scale AI’s own operation in the Philippines, which Hashme helped manage, was criticized in 2023 by rights groups for not abiding by basic labor standards and failing to pay workers properly and on time, according to an investigation by the Washington Post.

In a statement, OpenAI said such work “needs to be done humanely and willingly,” and that the company establishes “ethical and wellness standards for our data annotators.” In a response to questions about criticisms of its operation in the Philippines, Scale AI wrote, “Over the past year alone, we’ve paid out hundreds of millions in earnings to contributors, giving people flexible work options and economic opportunity,” and that “98% of support tickets regarding pay have been successfully resolved.”

Hashme says he was not aware of the allegations against Scale AI during his time there, which ended in 2019. But, he said in an email, “we did make mistakes, which we quickly corrected and generally took quite seriously.” I asked him what lessons he takes from the allegations against Scale AI and other companies outsourcing sensitive data work and what safeguards he’s putting in place for the team he’s building in the Philippines for Prosper, which so far numbers about 10 people.

“A lot of companies that do that kind of stuff end up doing it in a way which is kind of shitty for the people who are being employed,” Hashme told me. Such companies often outsource important HR activities to untrustworthy partners abroad or lose workers’ trust through bad incentive programs, he said, adding: “With a more experienced and closely managed team, and a lot more transparency around the entire system, I expect we’ll be able to do a much better job.”

It’s worth disclosing the nature of Hashme’s departure from Scale AI, where he was hired in 2017 as its 14th employee. In May 2019, according to court documents, Scale noticed that someone had repeatedly withdrawn unauthorized payments of $140 and transferred them to multiple PayPal accounts. The company contacted the FBI. Over the course of five months, approximately $56,000 was taken from the company. An investigation revealed that Hashme, then 26, was behind the withdrawals, and in October of that year, he pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud. Ahead of his sentencing, Alexandr Wang, the now-billionaire founder and CEO of Scale AI, wrote a letter to the judge in support of Hashme, as did 13 other current or former Scale employees. “I believe Shariq is genuinely remorseful for his crime, and I have no reason to believe he will ever do something like this again,” Wang wrote, and he said the company would not have wanted the wrongdoer prosecuted if it had known it was Hashme.

Hashme lost his job, his stock options, and Scale’s sponsorship of his green card application. Scale offered him a $10,000 severance payment before leaving, which he declined to accept, according to Wang’s letter. Hashme paid the money back in 2019, and in February 2020, he was sentenced to three months in federal prison, which he served. Wang is now a primary investor in Prosper Robotics, alongside Ben Mann (cofounder of Anthropic), Simon Last (cofounder of Notion), and Debo Olaosebikan (cofounder and CEO of Kepler Computing).

“I had a major lapse in judgment when I was younger. I was facing some personal challenges and stole from my employer. The consequences and the realization of what I’d done came as a shock, and led to a lot of soul-searching,” Hashme wrote in an email in response to questions about the crime. At Prosper, he wrote, “we’re taking trustworthiness as our highest aspiration.”

There are some real upsides to being able to control robots remotely, but the idea of large-scale robotic teleoperation by overseas workers, even if it takes years for it to be effective, would be nothing short of a seismic shift for labor. It would present the possibility that even highly localized physical work that we perceive as immune to moving offshore—cleaning hotel rooms or caring for hospital patients—might someday be conducted by workers abroad. It also seems antithetical to the very idea of a trustworthy robot, since the machine’s effectiveness would be inextricably tied to a faceless worker in another country, most likely receiving paltry wages.

Hashme has spoken about using a portion of Prosper’s profits to make direct payments to people whose jobs have been affected or replaced by Alfies, but he doesn’t have specifics on how that would work. He’s also still thinking through issues related to who or what Prosper’s customers should be trusting when they allow its robot into their home.

“We don’t want you to have to place as much trust in the company or the people the company hires,” he says. “We’d rather you place trust in the device, and the device is the robot, and the robot is making sure the company doesn’t do something they’re not supposed to do.”

He admits that the first version of Alfie will likely not live up to his highest aspirations, but he remains steadfast that the robot can be of service to society and to people, if only they can trust him.