Subtotal: 20.473,93€ (incl. VAT)

Why we need to shoot carbon dioxide thousands of feet underground

This article is from The Spark, MIT Technology Review’s weekly climate newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Wednesday, sign up here.

There’s often one overlooked member in a duo. Peanut butter outshines jelly in a PB&J every time (at least in my eyes). For carbon capture and storage technology, the storage part tends to be the underappreciated portion.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) tech has two main steps (as you might guess from the name). First, carbon dioxide is filtered out of emissions at facilities like fossil-fuel power plants. Then it gets locked away, or stored.

Wrangling pollution might seem like the important bit, and there’s often a lot of focus on what fraction of emissions a CCS system can filter out. But without storage, the whole project would be pretty useless. It’s really the combination of capture and long-term storage that helps to reduce climate impact.

Storage is getting more attention lately, though, and there’s something of a carbon storage boom coming, as my colleague James Temple covered in his latest story. He wrote about what a rush of federal subsidies will mean for the CCS business in the US, and how supporting new projects could help us hit climate goals or push them further out of reach, depending on how we do it.

The story got me thinking about the oft-forgotten second bit of CCS. Here’s where we might store captured carbon pollution, and why it matters.

When it comes to storage, the main requirement is making sure the carbon dioxide can’t accidentally leak out and start warming up the atmosphere.

One surprising place that might fit the bill is oil fields. Instead of building wells to extract fossil fuels, companies are looking to build a new type of well where carbon dioxide that’s been pressurized until it reaches a supercritical state—in which liquid and gas phases don’t really exist—is pumped deep underground. With the right conditions (including porous rock deep down and a leak-preventing solid rock layer on top), the carbon dioxide will mostly stay put.

Shooting carbon dioxide into the earth isn’t actually a new idea, though in the past it’s largely been used by the oil and gas industry for a very different purpose: pulling more oil out of the ground. In a process called enhanced oil recovery, carbon dioxide is injected into wells, where it frees up oil that’s otherwise tricky to extract. In the process, most of the injected carbon dioxide stays underground.

But there’s a growing interest in sending the gas down there as an end in itself, sparked in part in the US by new tax credits in the Inflation Reduction Act. Companies can rake in $85 per ton of carbon dioxide that’s captured and permanently stored in geological formations, depending on the source of the gas and how it’s locked away.

In his story, James took a look at one proposed project in California, where one of the state’s largest oil and gas producers has secured draft permits from federal regulators. The project would inject carbon dioxide about 6,000 feet below the surface of the earth, and the company’s filings say the project could store tens of millions of tons of carbon dioxide over the next couple of decades.

It’s not just land-based projects that are sparking interest, though. State officials in Texas recently awarded a handful of leases for companies to potentially store carbon dioxide deep underwater in the Gulf of Mexico.

And some companies want to store carbon dioxide in products and materials that we use, like concrete. Concrete is made by mixing reactive cement with water and material like sand; if carbon dioxide is injected into a fresh concrete mix, some of it will get involved in the reactions, trapping it in place. I covered how two companies tested out this idea in a newsletter last year.

Products we use every day, from diamonds to sunglasses, can be made with captured carbon dioxide. If we assume that those products stick around for a long time and don’t decompose (how valid this assumption is depends a lot on the product), one might consider these a form of long-term storage, though these markets probably aren’t big enough to make a difference in the grand scheme of climate change.

Ultimately, though of course we need to emit less, we’ll still need to lock carbon away if we’re going to meet our climate goals.

Now read the rest of The Spark

Related reading

For all the details on what to expect in the coming carbon storage boom, including more on the potential benefits and hazards of CCS, read James’s full story here.

This facility in Iceland uses mineral storage deep underground to lock away carbon dioxide that’s been vacuumed out of the atmosphere. See all the photos in this story from 2022.

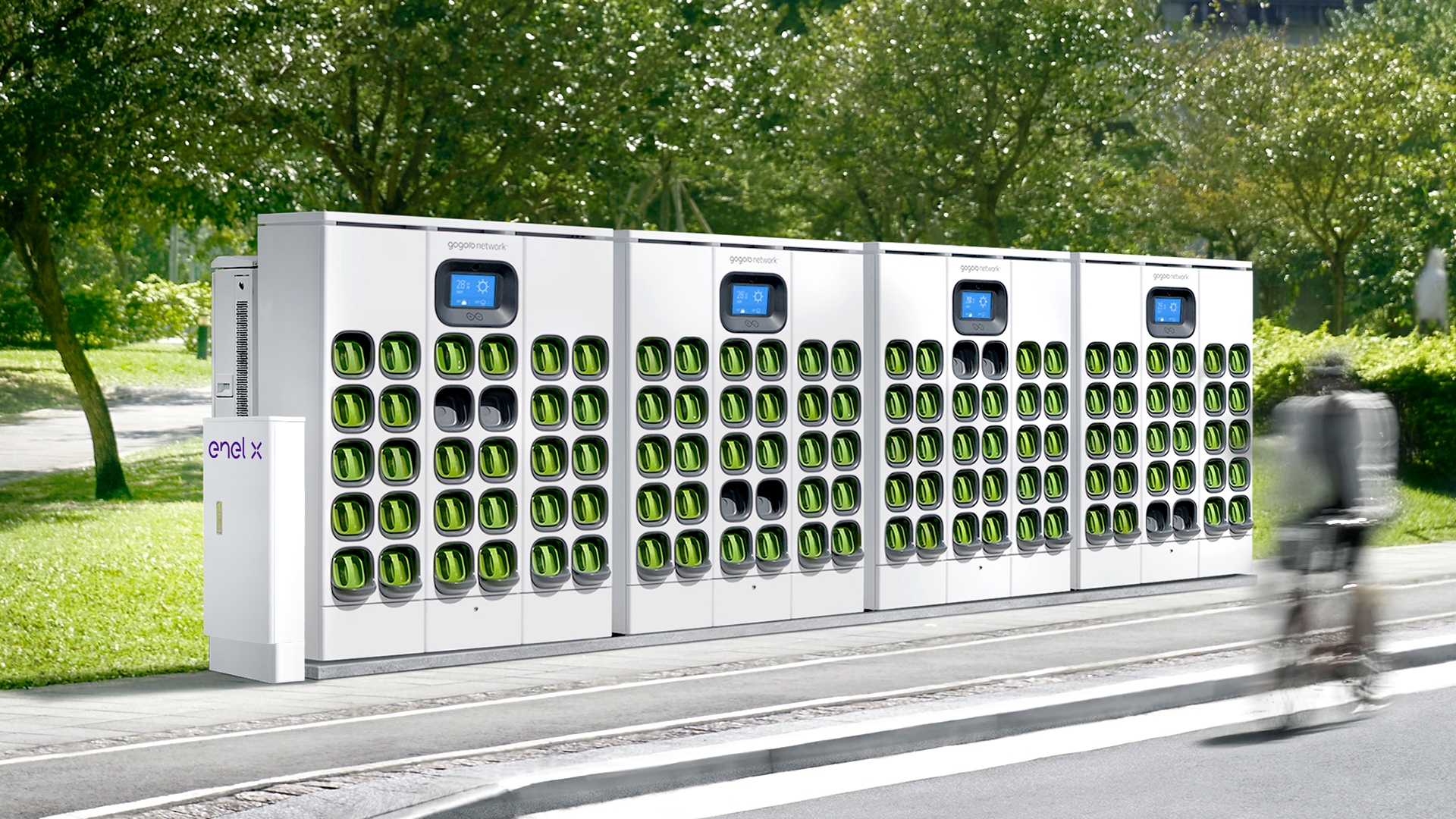

GOGORO

Another thing

When an earthquake struck Taiwan in April, the electrical grid faced some hiccups—and an unlikely hero quickly emerged in the form of battery-swap stations for electric scooters. In response to the problem, a group of stations stopped pulling power from the grid until it could recover.

For more on how Gogoro is using battery stations as a virtual power plant to support the grid, check out my colleague Zeyi Yang’s latest story. And if you need a catch-up, check out this explainer on what a virtual power plant is and how it works.

Keeping up with climate

New York was set to implement congestion pricing, charging cars that drove into the busiest part of Manhattan. Then the governor put that plan on hold indefinitely. It’s a move that reveals just how tightly Americans are clinging to cars, even as the future of climate action may depend on our loosening that grip. (The Atlantic)

Speaking of cars, preparations in Paris for the Olympics reveal what a future with fewer of them could look like. The city has closed over 100 streets to vehicles, jacked up parking rates for SUVs, and removed tens of thousands of parking spots. (NBC News)

An electric lawnmower could be the gateway to a whole new world. People who have electric lawn equipment or solar panels are more likely to electrify other parts of their homes, like heating and cooking. (Canary Media)

Companies are starting to look outside the battery. From massive moving blocks to compressed air in caverns, energy storage systems are getting weirder as the push to reduce prices intensifies. (Heatmap)

Rivian announced updated versions of its R1T and R1S vehicles. The changes reveal the company’s potential path toward surviving in a difficult climate for EV makers. (Tech Crunch)

First responders in the scorching southwestern US are resorting to giant ice cocoons to help people suffering from extreme heat. (New York Times)

→ Here’s how much heat your body can take. (MIT Technology Review)

One oil producer is getting closer to making what it calls “net-zero oil” by pumping captured carbon dioxide down into wells to get more oil out. The implications for the climate and the future of fossil fuels in our economy are … complicated. (Cipher)