Why NASA should visit Pluto again

In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh, a 25-year-old amateur astronomer, spied a small, dim object in the night sky.

He’d been working at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, for about a year when he used a blink comparator—a special kind of microscope that can examine and compare images—to glimpse what was for a time considered to be the ninth planet in our solar system: Pluto.

By all accounts, Pluto was—well—weird. At one point, astronomers believed it could potentially be bigger than Mars (it’s not). Its unusual 248-year orbit has been known to cross Neptune’s path. Today, Pluto is recognized as the largest object in the Kuiper Belt—but it’s no longer considered a planet.

In 2006, the International Astronomical Union voted to downgrade Pluto, defining a planet as a body that orbits the sun, is round in shape, and has “cleared the neighborhood around its orbit”—meaning it has become gravitationally dominant, so that there are no bodies in its orbital zone besides its own moons. Since Pluto did not check that third box, it was deemed a dwarf planet.

Now a new concept mission submitted to NASA aims to take a close look at Pluto and its nearby systems. Proposed in late 2020, Persephone would explore whether Pluto has an ocean and how the planet’s surface and atmosphere have evolved.

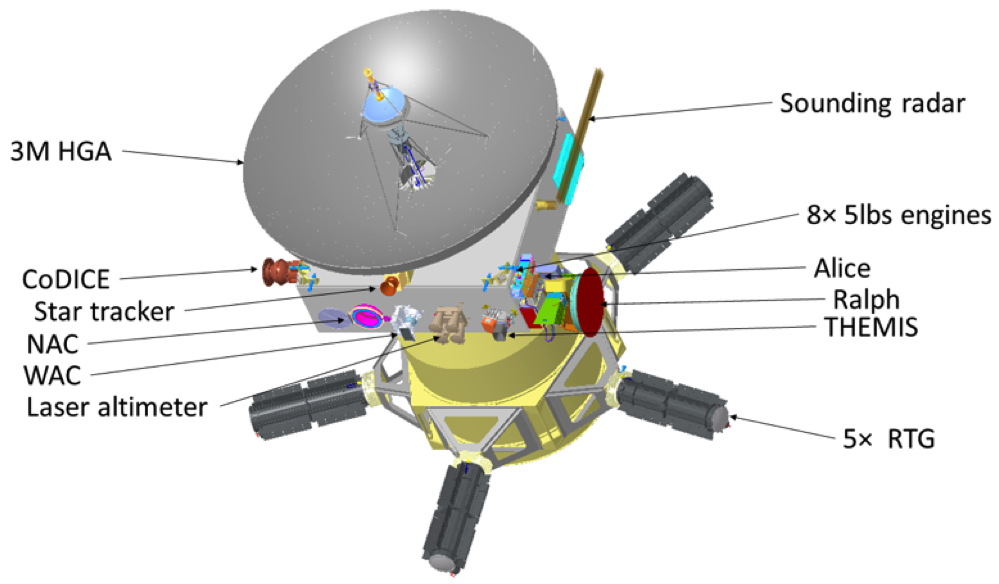

Persephone would send a spacecraft armed with high-resolution cameras to orbit Pluto for three years and map its surface as well as that of its largest moon, Charon.

But why is Pluto worth visiting?

The same year Pluto was shoved from its planetary pedestal, NASA sent the New Horizons mission to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt to better understand the outer edge of our solar system.

After reaching Pluto in 2015, New Horizons struck what amounted to scientific treasure. Close-ups of Pluto revealed potentially active mountain ranges, flowing ice, and a surprising record of geologic history on its surface.

Carly Howett, a planetary physicist and the principal investigator for Persephone, says New Horizons showed us just how complex that part of space really is.

“It wasn’t that New Horizons fundamentally had technology that is new, but it kind of gave people an insight into what the Pluto system might be like,” Howett says. “The world, for the first time, saw Pluto.”

Now, Howett and others think it’s time to return. Every 10 years, the National Research Council’s decadal survey raises leading questions posed in space exploration and determines what kinds of missions could answer them. Persephone’s goals address questions raised in the last survey about the formation of the solar system and whether organic matter once existed outside of Earth.

To become an official NASA mission, Persephone will have to prove to the larger scientific community that the questions it may answer are worth the effort, before the NRC takes it to a vote.

However, some scientists believe that going back to Pluto isn’t worth the resources or the 30-year trip it would take to get there.

“In a perfect world we would be constantly putting together new missions to anything we could land a rover on,” says Dakotah Tyler, an astronomy PhD student at UCLA who studies exoplanets (planets orbiting stars other than our sun). But because NASA invests only in top science priorities, resources are limited.

Instead of Pluto, Tyler says, we should go to the moons of Saturn and Jupiter, many of which we already know are home to oceans below their surface.

“Although we undoubtedly would gain more knowledge by continuing to study the icy Kuiper Belt objects, I think that we stand to gain far more, far quicker if we keep our exploration a bit closer to home,” says Tyler.

And as with any mission, there are risks and challenges involved in getting Persephone off the ground. One of the biggest would be maintaining its power source—an array of radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or what amount to nuclear batteries—on such a long journey. Any changes could affect both the size of the spacecraft and the price tag, estimated to be a whopping $3 billion.

Still, the team is excited by the prospect of doing its part to expand our knowledge of the universe by exploring Pluto.

Jani Radebaugh, a planetary scientist and professor of geology at Brigham Young University, is the Persephone team’s geologist, and she says the New Horizons findings caught her by surprise.

“I think my prediction was this is going to be a cold and dead and cratered surface, because it’s so far out—it’s pretty small. And that’s just what we expect from small, icy bodies,” says Radebaugh. “But I was just completely amazed at what I saw. Instead, there was just a real diversity of landscapes and processes.”

As for how long it would take to reap the benefits of a new mission to Pluto, Radebaugh said that even if she never sees it to completion, she hopes her efforts will benefit the next generation of space scientists.

“We can get out to the outer reaches of the solar system,” she says. “It is interesting and bizarre and exciting beyond our wildest dreams.”