Subtotal: 326,34€ (incl. VAT)

Why it’s so hard to tell porn spam from Chinese state bots

China Report is MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology developments in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

A few weeks ago, at the peak of China’s protests against stringent zero-covid policies, people were shocked to find that searching for major Chinese cities on Twitter led to an endless stream of ads for hookup or escort services in Chinese. At the time, people suspected this was a tactic deployed by the Chinese government to poison the search results and prevent people from accessing protest information.

But this spam content may not have had anything to do with the Chinese government after all, according to a report published on Monday by the Stanford Internet Observatory. “While the spam did drown out legitimate protest-related content, there is no evidence that it was designed to do so, nor that it was a deliberate effort by the Chinese government,” wrote David Thiel, the report’s author.

Instead, they were likely just the usual commercial spam bots that have plagued Twitter forever. These particular accounts exist to attract the attention of Chinese users who go on foreign networks to access porn.

So the “significant uptick” in spam was just a coincidence? The short answer is: very likely. There are two major reasons why Thiel does not think the bots are related to the Chinese government.

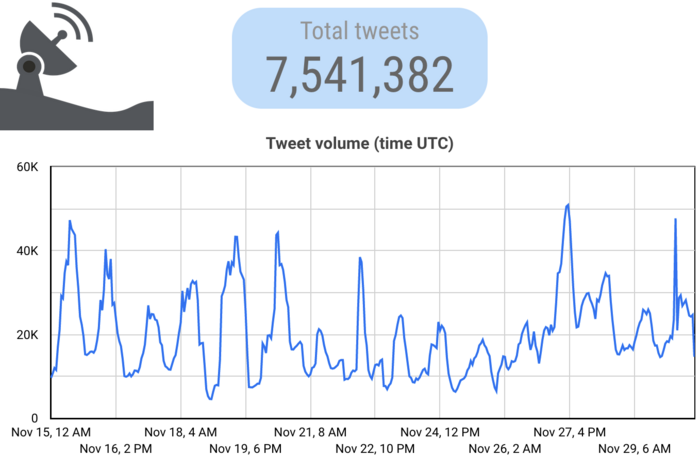

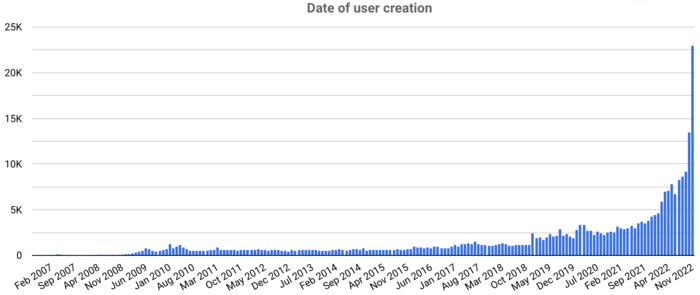

First of all, these accounts have been posting spam for a long time. And they sent out even more tweets, and more consistently, before the protests broke out, according to a data analysis on the activities of over 600,000 accounts from November 15 to 29. Another analysis shows they’ve also continued to push out spam even as discussions of the protests have died down.

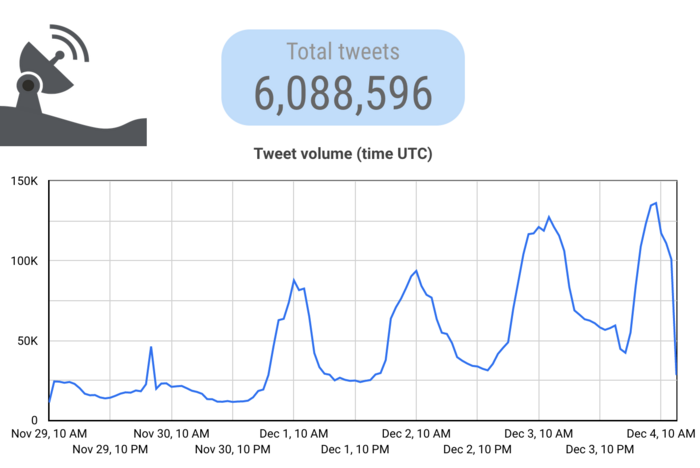

Check out these two charts (for reference, the protests peaked around November 27):

So did it just feel as if spam activity spiked during the protests? This graph shows that many more bot accounts were in fact created in November:

But Thiel emphasizes that content moderation takes time. People tend to ignore the effect called “survivorship bias”: older spam content and accounts are constantly being removed from the platform, but researchers don’t have data on suspended accounts. So a graph like this one only shows accounts that survived Twitter’s spam filters. That’s why November’s spike looks so big: they are new accounts created most recently to replace their dead peers and are still standing—but not all will survive, so they wouldn’t be there if we were to revisit this graph in, say, a few months. In other words, if you conducted a data analysis right after the protests, it would certainly seem that this kind of spam just started recently. But it’s not necessarily the full truth.

Secondly, if the spam accounts were meant to bury information about the protests, they did a pretty poor job. While escort-ad spam featured many Chinese city names as keywords and hashtags, Thiel found that they did not target the hashtags actually used to discuss the protests, like #A4Revolution or #ChinaProtest2022, “which is what you would assume the government would be interested in jumping on if they were trying to silence things,” he tells me. Of the about 30,000 tweets he analyzed containing these more influential hashtags, “there’s no spam to speak of in there.”

“People tend to jump to a state explanation for things just because the content is in Chinese,” he says. “Sure, China’s done tons of online inauthentic operations before. But I don’t think the default assumption should be [that] the state is behind this.”

Given all this, Thiel believes that the porn ads during this time were probably just run-of-the-mill commercial spamming, which can actually be quite lucrative. Because of the more rigid porn censors on domestic platforms, Chinese people often seek alternative sources for porn, including using innovative outlets like Steam or just using a plain old VPN to access international platforms like Twitter, which is known for being one of the mainstream platforms more tolerant of sexual content.

That makes Twitter a prime space for sex-work ads—and, of course, scams. Reporters from the New York Times talked to an online advertising company behind such spam, which charged $1,400 for a monthlong campaign. Some of these accounts may lead to real sex services or access to “premium group chats,” where porn content is shared. Others are fraudulent; as Chinese internet users have exposed, they may ask you to pay upfront online for potential services, in the form of things like “transportation fees.” Once they extract as much money as possible from you, the scammers will cut off all communications. In fact, there are even Twitter accounts in Chinese (NSFW!) dedicated to exposing such scammers and the relevant accounts.

But not everyone knows the context of how Twitter is used by Chinese people to access porn, or that such spam has existed for a long time. So I don’t blame anyone for suspecting that the government was involved. In the end, I think there are two main reasons why people easily bought the assumption that the spam accounts were part of China’s propaganda machine.

As Thiel said, the Chinese government has been behind many Twitter manipulation campaigns in the past, deploying fake personas, automated activities, and targeted harassment. Back in 2019, for instance, it used spam accounts to disseminate pro-China messages and attack Hong Kong pro-democracy protesters. Some of those accounts had posted extensive porn content—sounds familiar, hah?

But Elise Thomas, a senior analyst at the Institute for Strategic Dialogue who analyzed the 2019 campaign, tells me that was a totally different situation. She found bot accounts that had been used for commercial porn spam and were later sold to Chinese government actors to push political messages, without deleting the account history: “They might buy old commercial accounts, and some of the commercial accounts had done porn, spam, cryptocurrency, and all sorts of other stuff.” So it was not the Chinese government that was deliberately posting porn, but the previous owners of the bots.

Obviously, the state’s tactics could evolve, but it’s important not to give the state too much credit for its capacity to meddle with social media.

Last but not least, it’s just generally hard to tie any social media activity to a foreign government when researchers don’t have access to internal company analytics.

“Only social media companies can definitively link social media accounts to the Chinese government based on technical indicators to which they only have access. It is very difficult to distinguish between random accounts and possibly state-affiliated ones based solely on open-source methods,” says Albert Zhang, who researches Chinese disinformation at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute. “We make probabilistic assessments based on behavioral patterns found in previous Chinese government campaigns that Twitter and Meta have publicly disclosed.”

Before Elon Musk acquired Twitter, it was one of the best social networks in terms of being transparent to outside researchers and sharing data with them, according to the researchers I spoke with. But even then, Twitter still withheld the internal data it used to determine whether an account was linked to a foreign government.

Now, as the platform gets into bigger messes, this kind of academic collaboration is increasingly endangered. “That’s the big unknown right now. Normally with this kind of situation, we would be working with Twitter and seeing if they had seen this campaign, seeing what might be able to be done to tamp it down and prevent this kind of thing,” Thiel tells me. But after the mass exodus of Twitter staffers, no employees that used to work with the Stanford Internet Observatory are still on the team. These researchers have no direct contact at the company now.

Identifying and exposing foreign governments’ influence campaigns is already a hard job. Without the collaboration between tech platforms and researchers, it will be even more difficult to correctly hold governments accountable. Will it ever get better under Musk?

Did you think these accounts were linked to the Chinese government? Why or why not? I’d love to hear your thoughts at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

Catch up with China

1. China announced the first two deaths from covid since disbanding much of its zero-covid infrastructure. (Associated Press)

- But many more deaths have likely gone unreported. One crematorium worker in Beijing said the facility had received over 30 bodies with covid in one day. (Financial Times $)

2. China is planning to pour another 1 trillion yuan ($143 billion) into subsidizing domestic chip industries. (Reuters $)

3. After the Chinese government agreed to let the US audit whether some Chinese companies are making military products, the US Commerce Department added 36 Chinese entities to the trade blacklist—but, in a win for China, removed 25 from the unverified list. (Financial Times $)

4. Using jokes, old photos, and protest news, Chinese Instagram meme accounts are creating a bridge between diaspora communities and Chinese youths at home. (Wired $)

5. Both national and state lawmakers in the US are pushing to ban TikTok from government phones. (South China Morning Post $)

6. A Chinese company tried to launch the world’s first methane-fueled rocket. It failed. (Space News)

7. Ford is working on a complex arrangement to build a battery factory in Michigan along with China’s battery giant Contemporary Amperex Technology—without triggering geopolitical concerns. (Bloomberg $)

8. Acting tough on China is one of the few things both parties can agree on in Washington. But Cornell government professor Jessica Chen Weiss, who spent a year in the Biden administration, is publicly challenging that consensus. (New Yorker $)

- The Biden administration launched an interdepartmental coordination mechanism named “China House.” (Politico)

9. Writer Sally Rooney is gaining literary fans in China, both because Chinese youths see themselves in her work and because her Irish nationality has shielded her from worsening US-China relations. (The Economist $)

Lost in translation

As cities across China struggle to deal with a covid infection surge, OTC fever medicine has become the hottest commodity. But how did such a common medicine as ibuprofen sell out so widely and so fast?

Industry insiders told Chinese health-care news publication Saibailan that many domestic pharmaceutical companies were disincentivized from manufacturing ibuprofen this year because until China relaxed its covid control measures in December, Chinese citizens were heavily restricted from purchasing fever medicine. Even though demand is up now, the ibuprofen supply chain needs time to recover and respond.

To speed things up and ensure medicine supply, local governments are stepping in. Some have asked pharmacies to ration the drug and sell no more than six capsules to each customer. Other governments are even taking over pharmaceutical factories to make sure products are supplied to local patients first before they’re sold to other regions in China.

One more thing

Don’t miss the most viral Chinese internet slang of this year, a list put together by a local publication in Shanghai. The top 10 is a mix of covid-era creations like 团长 (tuan zhang), the volunteers organizing bulk-orders of groceries during Shanghai’s two-month lockdown, and social media phenomena like 嘴替 (zui ti), which means someone who can publicly speak out on things normies don’t dare to say or can’t articulate. And the top one is also the one I find most bewildering: 栓Q (shuan Q), which is really just a dramatic way to pronounce “thank you” when people feel speechless or fed up. Maybe internet trends don’t need to make sense. Just saying.