What happens when you donate your body to science

Rebecca George doesn’t mind the vultures. They remind her of toddlers as they rustle their feathers in annoyance when she opens the gate of the Western Carolina University body farm early one July morning. Her arrival has interrupted their breakfast. George studies human decomposition, and part of decomposing is becoming food. Scavengers are welcome.

The birds complain from the trees that surround the body farm as George, a forensic anthropologist, begins her main task of the day: placing the body of a donor, whom we’ll call Donor X, in the Forensic Osteology Research Station—known as the FOREST. The enclosure sits on a steep incline in North Carolina’s temperate rainforest, surrounded by two layers of protective fencing. This is Enclosure One, where donors decompose naturally above ground. Just on the other side of the clearing is Enclosure Two, where researchers study bodies that have been buried in soil. She is the facility’s curator, a member of a small team of forensic anthropologists and university students who monitor the donors—sometimes for years—as they become nothing but bones.

George places Donor X on their back just inside the enclosure gates, hands at their sides. Unless donors are part of a specific study requiring clothes, they’re laid out “in their birthday suit.” Clothing slows decomposition. She sticks a little yellow flag next to the body with an ID number and the date. Another donor is nearby, one skeletonized hand gently resting on a small rock, head tilted to the right, as if they were sleeping.

Donor X’s next of kin chose for them to be laid out here in the FOREST upon their death. In the US, about 20,000 people or their families donate their bodies to scientific research and education each year. They do it because they want to make their deaths meaningful, or because they’re disenchanted with the traditional death industry. People can become organ donors—offering up, at their death, organs suitable for transplant into living people—by checking a box on their driver’s license in the US. But the practice of whole-body donation is less widely discussed.

Body donation can also be cheaper than conventional cremation or burial. Some donation programs will pay for the cost of transporting a donor within a certain distance and, if the program is one that promises to eventually return remains to the family, for cremation. At the FOREST, the donors’ remains become permanent residents in the university’s forensic anthropology archives.

Whatever the reason someone chooses to donate, the decision becomes a gift. Health care needs death care; the bodies of the dead have long taught and trained the living. Many donor bodies go to medical schools, where students use them to learn anatomy and practice procedures. Others, like Donor X, go to university research facilities, or any of several private companies in the US that take body donations. Western Carolina’s FOREST, founded in 2003, is the second-oldest body farm in the US. A much larger facility at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, opened in 1981, is the oldest. These are places where watchful caretakers know that the dead and the living are deeply connected, and the way you treat the first reflects how you treat the second.

I visited the FOREST and another facility, the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s anatomy lab, to understand what happens when body donation works as intended.

Adam Puche walked me into the anatomy lab at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, where he is a professor and vice chair of the anatomy and neurobiology department, just as a class was wrapping up. Two students zipped a bag around their donor as they quietly cleaned their work station, and then draped a light blue cloth over the table.

Maryland has a highly regulated process for body donation, governed by a central anatomy board in the state’s health department; Puche is its chair. This particular lab handles about 4,000 bodies a year. Here, donors become patients for doctors in training. When a body arrives at the anatomy board, the individual is issued a tracking number. Then an RFID chip is implanted in one shoulder—a step unique to Maryland’s state program.

The lab is secured both by ID badges and by Puche’s own rigorous standards. The timing of my visit was carefully planned to minimize the impact on students. When I asked to take a reference photo of a cabinet of wet specimens showing livers, gall bladders, and other organs from donors with specific medical conditions, Puche politely shook his head. The work of protecting donors’ dignity extends to those represented in the museum, who lived a century ago. This is what he’s trying to teach future physicians, who are supposed to treat body donors as they would a living patient. In addition to what’s on the intake form, students at Maryland are expected to keep charts on donors. As they discover new conditions a patient may have—a cyst, a past broken bone, a previous surgery—they note it. Students are required to follow HIPAA rules when discussing their donors outside the lab.

“These are going to be physicians from day one,” said Puche. “We need them to be exercising the appropriate language choices, appropriate actions. So not only do I firmly believe in what I’m telling you as the right way to do it; it’s important for all faculty members to continuously and consistently display that to our students.”

Puche’s lab will soon be renovated to realize his vision for a space that reflects the working conditions of future doctors. The ’70s-chic fluorescent lighting will be supplemented with the same LED light systems and data access panels seen in operating rooms. As augmented-reality technology becomes more integrated into surgeries and other medical procedures, he expects, students might soon be able to see all the diagrams and instructions they need overlaid on their donor virtually.

I asked Puche if he sees a future in which technology eliminates the need for donors. He believes in technology’s potential to improve care, and he has run experiments offering VR training for medical students. In his opinion, however, none of these tools can replace the experience of working with a donor, so long as the living have real bodies too.

The process of donating one’s body begins with research, paperwork, and sometimes difficult conversations with family members. Funerals are the territory of the grieving, and it’s not always easy for loved ones to grieve without a body or its ashes. Some are aware of body donation because they know someone who made that choice. Others might search Google, looking for more affordable alternatives to burial.

Jeff Battersby, a 61-year-old who lives in Beacon, New York, learned about body farms from a 2017 podcast episode about a facility in Texas. Now he’s considering donating his body to one. “I’m not really fond of preserving a body for a million years in a casket, in the ground somewhere,” he says. “And I’m not really interested in going up in a puff of smoke. I just wanted to find and think about a way that was useful and giving.”

Battersby downloaded the paperwork to become a donor to the research facility at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville. But donating one’s body is a big decision to make. When we spoke last, he hadn’t yet sent in the forms or talked to his family about it.

Though dead bodies have been essential to medicine and research for centuries, consensual body donation, through programs like those at FOREST and Maryland, is relatively new. In the US, demand for bodies grew substantially in the mid-19th century as medical schools moved from having one person perform a dissection for an audience to providing each student with a hands-on lesson. That surge in demand drove body snatchers to steal bodies from graves to sell to medical schools. The bodies of the poor, the mentally ill, and people of color were especially vulnerable.

Things are very different now, thanks to new regulations and a better understanding of consent. But this grim history is still reflected in modern institutions. Until 2020, the University of Pennsylvania’s Penn Museum in Philadelphia had skulls on display that belonged to formerly enslaved people. And plenty can still go wrong even when donation is consensual. In August 2022, a Pennsylvania man was arrested for allegedly buying and selling human body parts via Facebook Messenger. At least some of the remains were initially donated to the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences. After the donor’s gift was used by the university, the remains were sent to be cremated at a non-university funeral home. There, the university said, a mortuary worker stole them.

Today, there’s no single federal regulation, registry, or tracking program that handles body and body part donations for research in the US. The American Association of Tissue Banks offers optional accreditation for these programs, but it’s not required by law. Instead, programs are largely governed by each state’s version of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, which contains provisions for promoting organ and tissue donation and outlines how people can consent to donate their organs or entire body to science. Whole-body donors must navigate these systems to decide where to donate. Some programs treat donors better than others do. And while there has been progress, body donation programs can still prey on those struggling to afford a conventional cremation or burial.

A major Reuters investigation in 2017 scrutinized “body brokers”—for-profit companies that accept donations and then sell partial and whole bodies to organizations engaged in training or research. When pitching potential donors and their families, these companies often emphasized the cost savings available, offering free cremation after the donated body served its purpose. As part of their reporting, Reuters was able to legally purchase body parts from one of these companies. They found out that the donor, from a low-income family, had been persuaded to donate for this reason. The family had no idea his body parts would be sold off.

That investigation prompted attempts to pass revised federal regulation in the US to oversee the industry, including an updated bill introduced into the House of Representatives last year that would require organizations accepting body donations to register with the US Department of Health and Human Services and follow uniform guidelines. That bill has not yet passed.

Not every body is welcome in every donation program. Most centers exclude those with certain communicable diseases, like HIV/AIDS or hepatitis B or C. Since 2020, many centers have also rejected donors who were positive for covid-19 when they died. And donation programs are not generally interested in waging custody battles with the next of kin, should that person decide not to honor a loved one’s intent. Some programs will not accept organ donors or bodies that have been previously autopsied.

Many facilities, including Western Carolina’s, also have weight limits for donors. Bodies there are carried into the facility by hand or on a gurney, often along steep and sometimes slick paths. Under university safety standards, employees can only move bodies that weigh 250 pounds or less. Without funding for the equipment needed to safely place larger donors, the FOREST is stuck with the limitation for now.

“It’s very frustrating, because we could get so many more donors if we didn’t have that weight limit,” George says.

Some dissection-based programs will not accept larger donors because dissecting a body that is carrying a lot of fat is more difficult and deemed less pleasant for students. But Maryland, which accepts thousands more donors a year than the 20 or so Western Carolina can handle, has never turned a body down for weight reasons. While Maryland’s program might not give a very large body to students performing their very first dissection, Puche says, “surgeons are going to need to work with somebody who may be 300 or 400 pounds. We expect our surgeons in training to work with our patient as the patient is.” As important as it is for them to get this practice, though, he believes his university is unusual in not exercising a weight limit.

Programs collect different kinds of information about donors. Western Carolina’s intake form asks for both biological sex and culturally expressed gender. Though Maryland’s form only asks for sex, Puche emphasizes that the anatomy board recognizes the gender identity of donors, and that living donors can use the “sex” field on the form to write in whatever best describes their identity. Students are expected to respect the identities and pronouns of the donors they work with.

But in some cases, the larger medical system’s failures in treating all patients with respect may prompt people to question the value of donating. Liam Hartle, a 30-year-old from Albany, New York, who has an autoimmune disorder, has thought seriously about donating his body. Maybe someone could learn something about the condition from studying him.

“There’s part of me that’s like, donating to science would be a really good idea,” he says. “But also? I’m a trans dude who hasn’t done any hormone therapy yet, because my husband and I are going to try to have a kid. Even if I had undergone any sort of physical transition, I don’t trust medical science to handle that delicately.”

After my time in Puche’s autopsy lab, I drove 10 hours from Maryland to North Carolina to see how Donor X was progressing. Nicholas Passalacqua, the director of Western Carolina University’s forensic anthropology program, approved my visit; the FOREST is not open to the public. As we pulled up to the gated facility, he told me that when he does bring visitors to the site—other researchers, students, or journalists like me, for instance—they often expect it to be disgusting, or gory, or terrifying.

Passalacqua and I stepped inside the enclosure, where George was already at work, training student volunteers. The group crouched over the skeleton of the donor who had been inside the enclosure the longest, since 2020. Patches of weeds had sprung up between donors but stayed away from the bodies themselves. Contrary to popular belief, decomposing bodies aren’t particularly good fertilizer in the short term—the fluids they release can inhibit plant growth.

As I adjusted to the smell—a sweet, rotting-fruit-like scent that crept into the back of my throat and stayed long after I left campus—I asked Passalacqua to tell me how to look at a body like a forensic anthropologist. His first lesson was that as donors decompose, they fill with life.

As we walked further into the enclosure, we came to a donor covered in sprinkle-size maggots: blowfly babies, laid by their mothers at the eyes, groin, and mouth. Those parts of the body, which liquefy first, are like baby food for the baby flies. As they work through the body, the busy bugs and gut bacteria leave the skin on the torso alone. The skin toughens on the ribs and becomes a weather and sun barrier, a little shaded tent.

Nicholas Passalacqua directs Western Carolina’s forensic anthropology program, which accepts about two dozen donated bodies each year.

“It’s a whole little microbiome, right?” Passalacqua said. “Where you have a body decomposing, you have insects eating, you have other things eating those insects, you have animals coming to eat the tissue, you have other animals coming to eat those animals.”

Donors who had been at the FOREST longer, though, were now more bone than flesh. “You can learn about somebody’s life history through their skeleton, so you can understand things that happen to them over the period of their life and how that manifests,” Passalacqua said.

Take ribs, for instance. George stood near a donor, almost entirely skeletonized, whose ribs were cracked. One might surmise that these broken ribs were a clue to how the person had died. But she says the bones were broken in the enclosure, from a vulture sitting on them. She wouldn’t have believed it herself if the whole thing hadn’t been captured on camera. Then she pointed to a body up on the plateau, at the far end of the enclosure. That donor, she said, did break their ribs when they died. The breaks looked totally different, the fractures more jagged. That’s because, George said, the breaks occurred in living bone, not after death when the material is more brittle. In a third body, Passalacqua pointed out a small spike on the rib. That, he said, was also a rib fracture, but one that had healed while the donor was alive.

Chronic illnesses and some other diseases can manifest in the bones. Tuberculosis can spread there, causing lesions. Forensic anthropologists can estimate a deceased young person’s age by understanding how the skeleton changes over time. Older adults, too, might have distinctive markers of age, like bone loss. But this work is difficult, and there’s still a lot scientists don’t know. Donors like these help them learn more.

George and Passalacqua’s job is to teach students, along with the law enforcement workers who occasionally train there, how to learn what you can from a body. Oftentimes, their first step is to figure out if a bone is human. Passalacqua regularly receives texts from local law enforcement asking about bones they’ve found—a partial skeleton of a bear paw looks shockingly like a person’s hand.

One of the hardest things for forensic anthropologists to do is also one of the most essential: estimating the time that has passed since death. “There are just so many variables that are really difficult to account for,” says Passalacqua. A reputable forensic anthropologist will rarely be able to say, for instance, that a body has been dead for exactly three weeks. More likely is a range of, say, one week to two months. That’s not as useful to law enforcement officers who are trying to solve a crime.

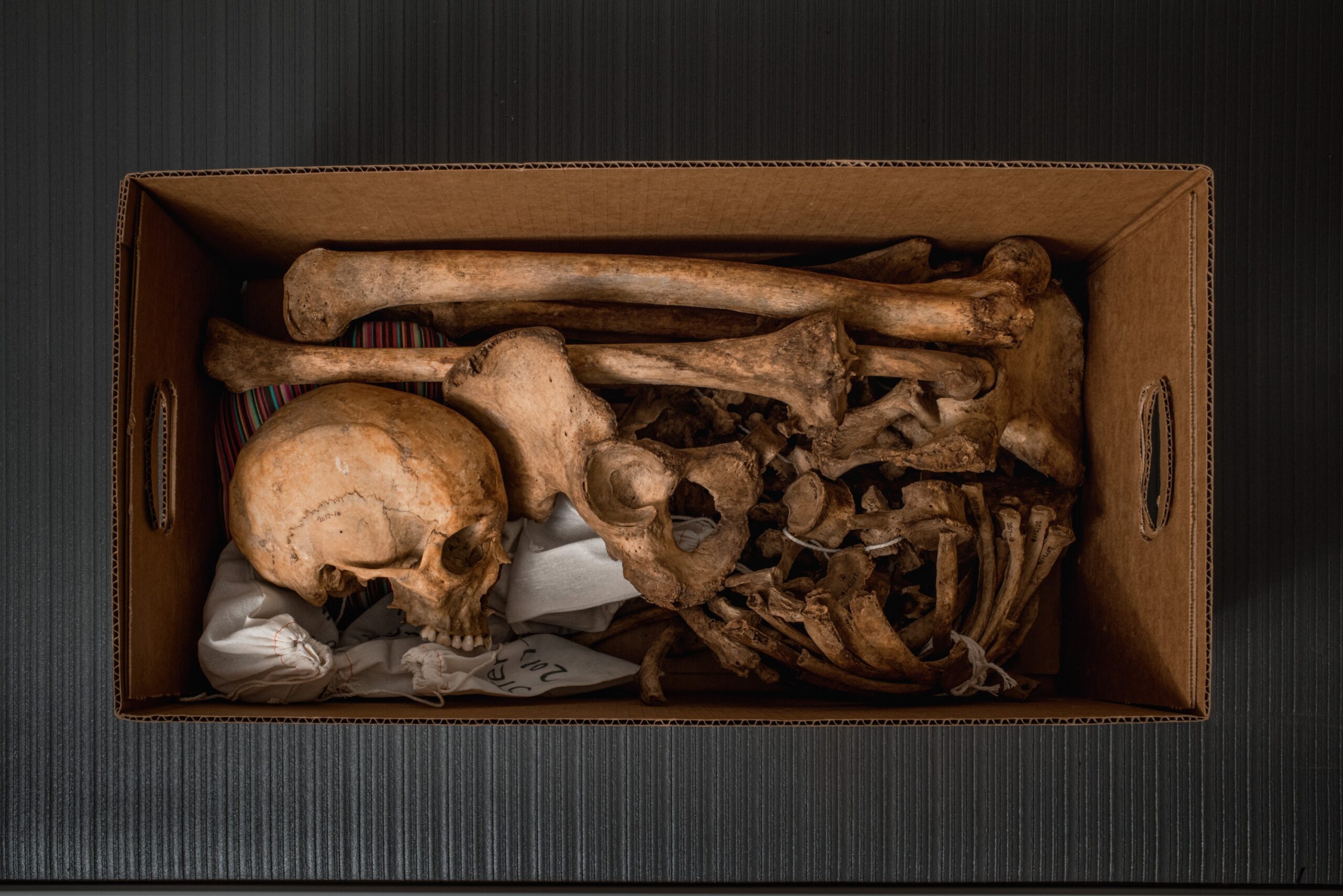

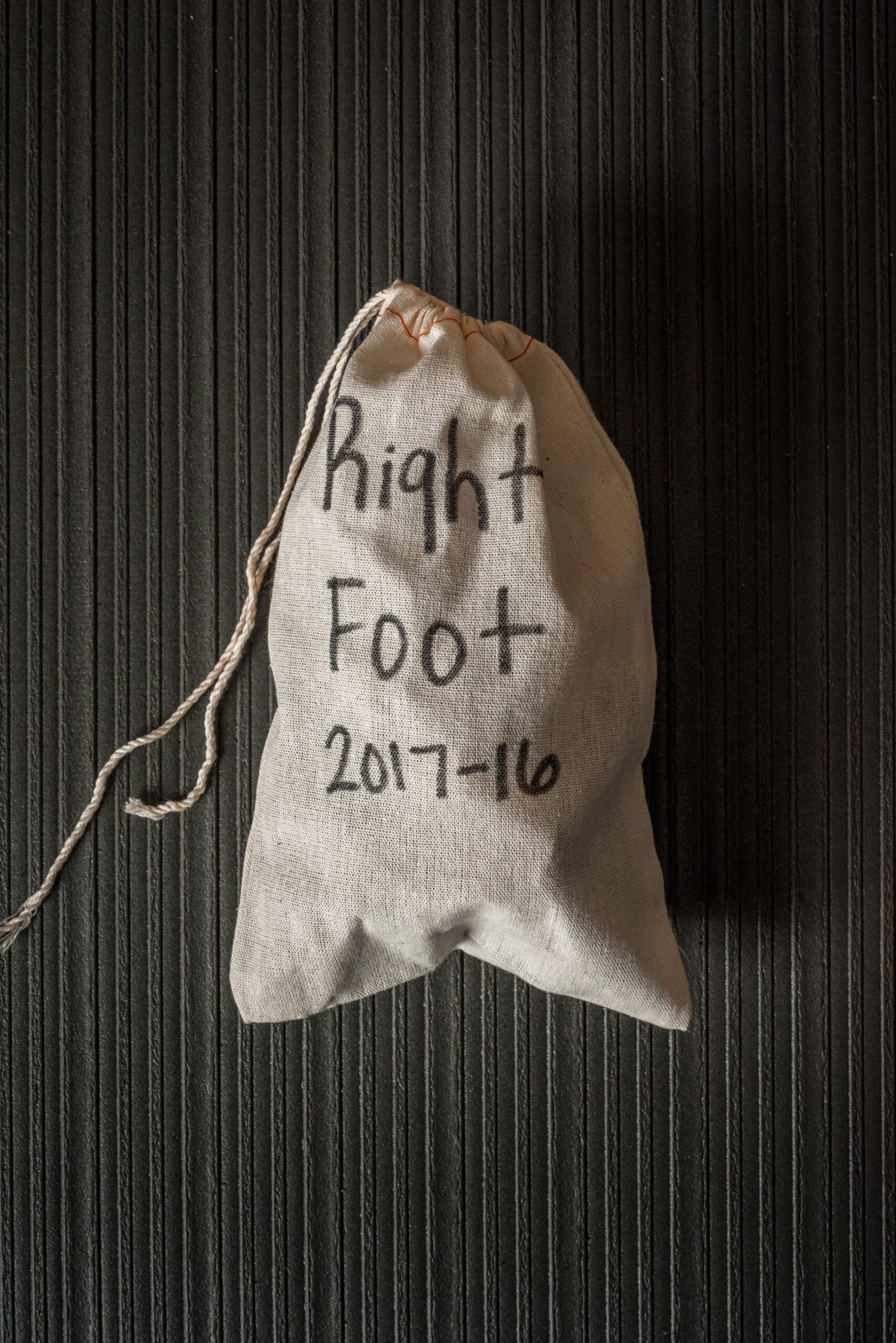

By the time I arrived, Donor X was already in advanced decay, but every day, this donor will teach living people something. When there’s little left on the bone, students will carefully remove the body from the FOREST and bring it to the lab. The bones will be cleaned by hand, and perhaps gently simmered to remove the last bits of tissue. They will be laid out and examined. And then they will be packed up, the delicate pieces placed in cheesecloth bags, and stored in the university’s collection, labeled in identical cardboard boxes.

But for now, Donor X remains in place, slowly becoming a unique microbiome. Dense trees filter the sunlight. The vultures aren’t there that morning, so as we walk and the students quietly examine a donor’s bones, the only other sounds we hear are the calls of cicadas.