Vaccine waitlist Dr. B collected data from millions. But how many did it help?

When Joanie Schaffer heard about Dr. B, a free covid-19 vaccine standby service, she was running out of options. It was early February, and vaccine appointments were scarce, so Schaffer, who was already vaccinated herself, was volunteering her time to help friends, family, and even strangers secure their shots.

She had read stories about people across the country stumbling upon vaccines that were about to expire: on a highway in Oregon during a snowstorm, or at pharmacies at the end of the day. And so when she heard about Dr. B, a new website which offered to notify people of waitlisted covid vaccines available nearby, it seemed worth a try.

The company had a simple proposition: provide your information, and Dr. B would scour the listings of vaccine providers nearby to find extra doses that needed to be used up. If there was a match, the patient would receive a text and get 15 minutes to reserve the shot. The service asked those signing up to give their name, zip code, date of birth, email, phone number, and type of work and to flag up any medical conditions such as asthma, cancer, or pregnancy.

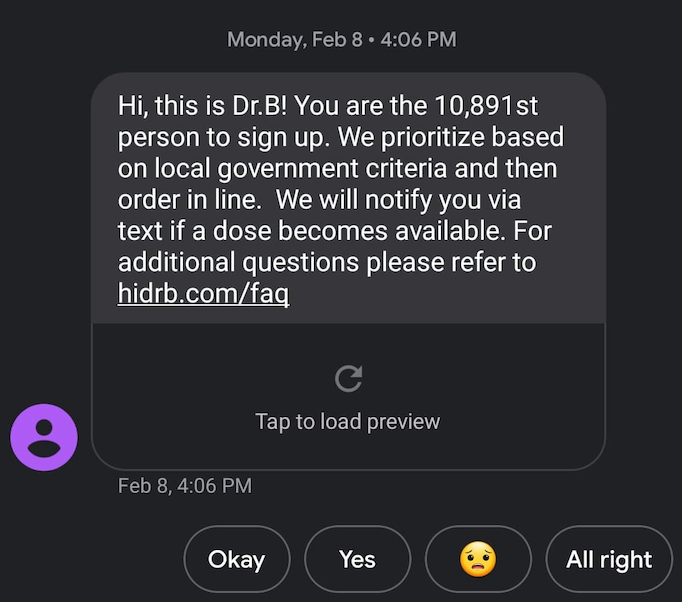

One of Schaffer’s contacts was a 70-something man from Brooklyn who had cancer and was eligible for vaccination but couldn’t find an appointment. “I signed up for Dr. B out of desperation,” Schaffer says: she got a message telling her the man was number 10,891 on Dr. B’s list.

Within weeks, that number had ballooned into the millions, thanks to coverage in the New York Times, Bloomberg, Time, and elsewhere—all emphasizing Dr. B’s promise to play matchmaker between sites with leftover doses and Americans desperate for a shot. (Today, it claims that nearly 2.5 million people have signed up for the service.) And people were desperate: appointment websites were breaking, some people were crowdsourcing their way to vaccination, and headlines suggested the country was in a race between vaccines and dangerous new variants.

But for Schaffer, the whole thing was just an exercise in false hope. Dr. B did not alert her to any standby appointments, so she carried on searching manually and eventually found the man an appointment herself. It was only on April 1, weeks after he had already gotten vaccinated, that she finally heard back from the service—and even then it didn’t offer an appointment but just the possibility of one. “You have a 50% chance of receiving an alert for a dose tomorrow,” the text message read. “Are you available tomorrow to get the COVID vaccine?”

By that time, though, vaccine appointments were abundant, and all New Yorkers over 30 were eligible.

The timing of the notification perplexed her, but it turns out that it was far from unusual.

I searched for people who had used Dr. B to actually receive a vaccination. I made phone calls to and exchanged messages with people who had signed up. I scoured online forums and neighborhood groups across the country. But after weeks of looking, I was unable to identify a single individual who successfully got a shot through the service. Instead, I heard from dozens of people all over the country who signed up but only received notice of available vaccines long after they had already been vaccinated elsewhere, as well as many others who say they were never contacted by the company after initial registration.

Karen Menendez, a moderator of a popular New York City Facebook group with nearly 10,000 members that acts as a hub for covid-19 information, says she’s seen discussion of Dr. B but has yet to encounter anyone who got a vaccine through the company.

The technology forged during this global health crisis—from video calling to contact tracing apps to vaccines themselves—has faced a special set of challenges. Systems often needed to be spun up quickly, in high-visibility environments, and with lives at stake. Under such pressures, few of these technologies have succeeded completely, and many have failed to live up to expectations. Building services to help people when they are at their most vulnerable is not easy.

To find out more, I asked Dr. B itself how many people it had gotten vaccinated. But after a series of verbal and written requests, and in an interview with its founder, Dr. B refused to say how many vaccines it had helped deliver, or to offer any other measure of success.

So I was left wondering: Did Dr. B achieve what it set out to do? And what is the company doing with its huge list of people’s names, locations, contact information, and health conditions?

The “national” waitlist

When he was touting Dr. B to the press shortly after starting the company in January 2021, founder Cyrus Massoumi explained what inspired him.

“I had this idea, reading all the articles,” Massoumi, a serial entrepreneur, told Bloomberg in March. “Why is there not a nationwide standby system that any provider could use that would effectively reallocate the vaccine?”

Dr. B was his answer to that question. The service doesn’t provide vaccines itself; instead, it relies on partnerships with official vaccination sites, which then notify it when they expect to have leftover doses. The company says it uses an algorithm to comb through its list of eligible nearby users and give them the option of reserving a dose.

Brittany Marsh, the owner and pharmacist of Cornerstone Pharmacy in Little Rock, Arkansas, was the first provider to sign on to work with Dr. B. She was introduced to the company through a mutual friend who knew Chelsea Clinton, a friend of Massoumi’s, she says. Company representatives flew to Arkansas to test the service and had it up and running “in record timing,” Marsh says.

“We were making calls and trying to get people in the door to save the shots in arms before they expired,” she says. Though the pharmacy wasn’t wasting any doses at the time, “it definitely made our life easier.”

In interviews given by Massoumi at the time, he talked about building a national network of providers. But when the company went on its publicity blitz in March, Marsh’s pharmacy was just one of two vaccination sites in the entire country that the company had agreements with. (The other was a vaccine hub in Queens, New York.)

Users were encouraged to sign up wherever they lived, but Dr. B did not tell them whether it had partnerships with vaccinators in their state or zip code.

The company has continued to promote the idea of a nationwide service, with online posts claiming the service “is available in all 50 states.” When asked exactly how large its network is, Massoumi told MIT Technology Review that Dr. B does not have nationwide coverage but has around 600 vaccination partners across 37 states—although the company declined to say who they are, or which states it is active in. And those partnerships do not include national-level agreements with major chains such as CVS or Walgreens, which both said they were not working with Dr. B at a corporate level, though Massoumi says some individual stores are Dr. B providers. Six hundred partners may seem extensive, but it accounts for less than 1% of the more than 80,000 US vaccination sites tracked by the CDC.

Dr. B’s limited presence may come as a surprise, given its founder’s experience in digital health services. Massoumi previously cofounded Zocdoc, a popular online appointment search and booking site, and served as its CEO. He left Zocdoc in 2015 and went on to start Shadow, an app that helps reunite lost pets with their owners. While Dr. B—which Massoumi says he is funding himself—does not charge either users or partners for its services, it now has at least 56 employees, including a team of 30 organizers, most with a background in politics. In February it expanded even further, acquiring another waitlisting service, Vax Standby.

Despite this heavy investment, however, Dr. B’s footprint is apparently so small that Claire Hannan, the executive director of the Association of Immunization Managers, which represents and coordinates state vaccine campaigns across the entire country, says she was not even aware of Dr. B until she was interviewed for this story. In fact, says Hannan, the entire idea of a digitized waitlisting service is one that overwhelmed vaccination sites would have found hard to adopt.

“Getting providers to use a new reporting system or a new scheduling system, a new IT interface—that’s much more of a challenge than getting them to agree to accept and give the vaccine,” she says.

Private data vs. public health

Dr. B is one of many private efforts that we’ve seen emerge to fill the gaps in America’s health system, from the private covid-19 testing sites that have overtaken strip malls to health-care tech companies entrusted to schedule vaccine appointments. With all these developments, it’s become harder for consumers and patients to differentiate between public pandemic response and for-profit entities. Crowdsourced resource lists regularly mention Dr. B’s waitlist signup, for example, alongside official public health websites, the federally operated Vaccines.gov, notices from health-care providers, and other medical services.

But public health departments and private companies have different reasons for existing, even if the stated missions sound similar.

“The incentives are the opposite,” says Elizabeth Renieris, a tech and human rights fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Carr Center. “Public health and public interest concerns traditionally are not driven by profit or growth, or speed or efficiency, or any of those values.”

“The famous saying in business is, if you’re not paying, you’re the product,” says Kayte Spector-Bagdady, associate director of the Center for Bioethics and Social Sciences in Medicine at the University of Michigan. “Weight tracker apps will help you track your weight, or fertility applications will help track your cycle. But the business model is really being able to sell that data out the back end.”

There are rules in place under HIPAA, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, intended to stop oversharing of health data. But if a company is not one of the “covered entities,” then the rules don’t apply, and there is a well-established business model for private health companies that relies on collecting consumer health data and selling it or sharing it with third parties.

“The vast majority of these private-sector companies providing these tools are not going to be HIPAA-covered entities,” Renieris says. “It’s this displacement of the public interest by the private sector.”

Because Dr. B itself does not provide care, it is one of those entities not covered by HIPAA, and the data it collects falls outside the law’s protections. That means when people sign up for Dr. B’s services, their health information is not protected by HIPAA, but by whatever is outlined in the site’s privacy policy.

The FAQ section of Dr. B’s website says that thanks to its staff’s “decades” of experience dealing with HIPAA, it voluntarily adheres to those standards when storing and sharing user data, including encrypting the information. And its privacy policy does lay out some comprehensive-sounding protections. The website says it does not sell information that would identify people, and only shares users’ personal information with providers once they’ve opted in to receive a vaccine nearby. It also gives users the option to request that their personal data be deleted by sending a sequence of text messages to the service (although that fact is found halfway down the privacy policy page, and couched in legalese).

But the policy also gives Dr. B the right to use personal data internally for purposes other than vaccinations and, if the company gets bought, to transfer the data to the new owner. The company declined to say what happens to information from users who opt out of vaccine notifications, and its policy is equally silent on the issue.

Such collected information can be lucrative. The zip code you live in and whether you have asthma can be valuable for advertisers marketing treatments; private or industry-sponsored researchers looking to recruit study participants might want a list of people with autoimmune disorders. And though many Americans are used to giving up data in the age of invasive tracking by tech giants, Spector-Bagdady says health data is different from, say, information on what kinds of clothes you like to wear.

“There are only so many pairs of mom jeans that I can purchase, but if you have health data from millions of people who have insurance, to whom you can advertise and target very expensive drugs that the insurance will cover, then you’re into some really profitable areas in terms of drug development, drug marketing, algorithmic and machine-learning developments,” she says.

Some Dr. B users I spoke to said that they expect information about themselves to be shared among private companies. But others said they were so desperate to protect themselves and loved ones that they didn’t even consider what information they were handing over when they signed up.

Renieris says it’s hard enough in normal times to ask people to investigate every digital interaction to make sure they know what they’re signing up for and who they’re giving their data to. Add in the fear and urgency of a pandemic and it’s even more of a burden on the consumer.

“You begin to sign up for anything at that stage,” says Menendez, the Facebook group administrator. “I think that logic kind of goes out of the window.”

Going straight to the source

Without any evidence that Dr. B was successfully rerouting leftover doses, I still had questions, so I contacted the company to organize a conversation with its founder.

On May 17, I interviewed Massoumi over Google Meet. He was accompanied by his communications team, including at least one representative from a public relations firm specializing in crisis communications. During the course of our conversation, Massoumi talked about learning from Dr. B’s “highly scalable” system and said that the company had a commitment to equitable distribution of vaccines, but he refused to say how many patients had been vaccinated through Dr. B.

While the company was happy to publish the number of signups it had on its website, he claimed that revealing vaccination numbers would violate user privacy.

Massoumi said Dr. B is committed to data privacy, reiterating the company’s claim that its staff’s previous experience with HIPAA means it understands how to protect user data.

“Just because we’re not a covered entity under HIPAA doesn’t mean that we can’t hold our service providers to high standards of patient privacy,” he said.

The company has already navigated the transfer of user data on at least one occasion. When Vax Standby, the competing covid-19 vaccine waitlist, announced it was ceasing operations and merging with Dr. B, Vax Standby’s founders publicly promised to keep user data separate and not to automatically place its subscribers on Dr. B’s waitlist. Massoumi said he respected Vax Standby’s move, but that it wasn’t ideal.

“I don’t think that was in the public health interest,” he said. “I think many of those people could have benefited from the platform that we built.” (He added that Vax Standby user data was eventually deleted without being transferred.)

Some Dr. B users had told me that data sharing was an issue for them only in hindsight. They said how panicked they had become as vaccination slots seemed nonexistent, and how little attention they paid to the personal information they were handing over.

“I appreciate the fact that if perhaps an evil person was running this company, that they could do a lot of evil things in the world,” Massoumi said. “I assure you, that’s not my reason for doing this.”

I asked Massoumi more questions about how desperation may have driven people to sign up for services without scrutinizing them. But he began discussing a different topic instead: the number of Americans who do not have health insurance. When pressed, Massoumi ended the conversation.

“I don’t have time to get into it with you,” he said before leaving the call.

“A bizarre attempt”

After our interview, I sent a list of 20 questions to Dr. B representatives to request more information. My queries revolved around the company’s basic business model, its activities, and its privacy policies—and included a request for key details that Massoumi had earlier said he would provide.

Building new technologies is a hard job that has been dramatically complicated by the pandemic, but these were typical questions about its operations that any startup might expect. We asked how many vaccine notifications the company had sent out; how many people had received a vaccine through the service; and whether it had consulted with health-care providers about the service’s usefulness. We also asked what the business model for this free service was, and whether it would seek outside funding in the future.

Dr. B refused to share even basic information about its operations. Instead, the company sent back the following statement, claiming that our inquiries were a “bizarre attempt” to question Dr. B’s attempts to get people vaccinated.

“Dr. B was created during the height of the covid-19 crisis with the clear mission to save lives by rapidly getting vaccines into as many arms as possible because too many vaccines go to waste,” it said. “This important effort reflects the need to make vaccine distribution efficient and equitable and meet the urgent needs of underserved communities to help bring the pandemic to an end.

“We are proud to have helped nearly 2.5 million people sign up for notifications about immediately available vaccines through hundreds of providers nationwide. So we are entirely flummoxed by this bizarre attempt to treat such a civic-minded endeavor as anything other than a genuine and committed effort to remove barriers that prevent people from getting vaccinated.

“From day one we understood the importance of protecting users’ data and that is why we have developed robust policies and practices to keep their information private and secure. Our privacy policy makes it clear that user data is never rented, sold or shared with any third party inappropriately. As a completely opt-in service, users have the ability to permanently delete their data from Dr. B at any time.”

Solving a temporary problem?

There is no doubt that Dr. B tapped into a very real issue when it launched: at the time, finding an available appointment was impossible for all but the most internet savvy or well-connected. With so many people struggling to get a vaccine, even whispers of leftover doses that might be trashed were enough to cause anger and confusion.

Manual and digital systems started to proliferate to address the issue: pharmacies set up their own paper waitlists, and alongside Dr. B and Vax Standby, there were digital services like VaccinateCA, a crowdsourced effort to spot open slots in California, and TurboVax, a viral Twitter bot that shared available appointments online as they dropped.

For many people, stories of leftover—or, worse, wasted—vaccines were a particularly painful and visible example of health systems failing. But as vaccine supplies expanded, that moment quickly passed. Hannan, of the Association of Immunization Managers, says waste has actually been minimal compared with what’s accepted in other mass vaccination initiatives. The federal Vaccines for Children program, which provides kids with shots regardless of their family’s ability to pay, has an expected wastage rate of 5%, she says. Data about covid vaccines obtained by Kaiser Health News, meanwhile, show that the CDC recorded 182,874 covid vaccines thrown out in the first three months vaccinations were available—just 0.1% of the more than 147.6 million doses administered as of March 30. According to CDC data, 70% of recorded covid-19 vaccine wastage happened at CVS and Walgreens—both companies that confirmed they have no national-level partnerships with Dr. B.

As vaccines have grown easier to access, some broker services have shuttered. Cities like Philadelphia are asking residents to take themselves off local lists, and TurboVax, the Twitter bot, announced on May 11 that it was winding down.

The willingness of people to help strangers find vaccines—like Joanie Schaffer, the volunteer who tried using Dr. B to help people in New York, and other community efforts—has been a small sliver of hope in an otherwise terrible year. And those who have benefited from such kindness have made their gratitude known. When TurboVax creator Huge Ma said he was closing the service, he was overwhelmed by thousands of tweets, retweets, and responses.

“Thank you for everything you did for the community,” said one follower. “Thank you for helping my wife and me get our first shots!” wrote another. (Indeed, TurboVax followers showed their appreciation by raising more than $200,000 for small businesses in New York’s Chinatown when Ma asked for help amid rising anti-Asian violence.)

I looked through Dr. B’s feed for similar expressions of thanks from grateful, vaccinated users, and found none. But unlike its peers, the company has no plans to shut down even though the appointment crunch has largely passed. Instead, Massoumi and the company say they are looking to what comes next. He says maybe they’ll collaborate with mobile vaccination clinics, or focus on booster shots. And now that the vaccination chaos has largely passed in the US? He wants to take Dr. B overseas. After all, he told me during our interview, the US effort has come so far. “We’ve touched millions of people,” he said.

This story is part of the Pandemic Technology Project, supported by The Rockefeller Foundation.