Unleashing the potential of qubits, one molecule at a time

It all began with a simple origami model.

As an undergrad at Harvard, Danna Freedman went to a professor’s office hours for her general chemistry class and came across an elegant paper model that depicted the fullerene molecule. The intricately folded representation of chemical bonds and atomic arrangements sparked her interest, igniting a profound curiosity about how the structure of molecules influences their function.

She stayed and chatted with the professor after the other students left, and he persuaded her to drop his class so she could instead dive immediately into the study of chemistry at a higher level. Soon she was hooked. After graduating with a chemistry degree, Freedman earned a PhD at the University of California, Berkeley, did a postdoc at MIT, and joined the faculty at Northwestern University. In 2021, she returned to MIT as the Frederick George Keyes Professor of Chemistry.

Freedman’s fascination with the relationship between form and function at the molecular level laid the groundwork for a trailblazing career in quantum information science, eventually leading her to be honored with a 2022 MacArthur fellowship—and the accompanying “genius” grant—as one of the leading figures in the field.

Today, her eyes light up when she talks about the “beauty” of chemistry, which is how she sees the intricate dance of atoms that dictates a molecule’s behavior. At MIT, Freedman focuses on creating novel molecules with specific properties that could revolutionize the technology of sensing, leading to unprecedented levels of precision.

Designer molecules

Early in her graduate studies, Freedman noticed that many chemistry research papers claimed to contribute to the development of quantum computing, which exploits the behavior of matter at extremely small scales to deliver much more computational power than a conventional computer can achieve. While the ambition was clear, Freedman wasn’t convinced. When she read these papers carefully, she found that her skepticism was warranted.

“I realized that nobody was trying to design magnetic molecules for the actual goal of quantum computing!” she says. Such molecules would be suited to acting as quantum bits, or qubits, the basic unit of information in quantum systems. But the research she was reading about had little to do with that.

Nevertheless, that realization got Freedman thinking—could molecules be designed to serve as qubits? She decided to find out. Her work made her among the first to use chemistry in a way that demonstrably advanced the field of quantum information science, which she describes as a general term encompassing the use of quantum technology for computation, sensing, measurement, and communication.

Unlike traditional bits, which can only equal 0 or 1, qubits are capable of “superposition”—simultaneously existing in multiple states. This is why quantum computers made from qubits can solve large problems faster than classical computers. Freedman, however, has always been far more interested in tapping into qubits’ potential to serve as exquisitely precise sensors.

Qubits store information in quantum properties that can be easily disrupted. While the delicacy of those properties makes qubits hard to control, it also makes them especially sensitive and therefore very useful as sensors.

Qubits encode information in quantum properties—such as spin and energy—that can be easily disrupted. While the delicacy of those properties makes qubits hard to control, it also makes them especially sensitive and therefore very useful as sensors.

Harnessing the power of qubits is notoriously tricky, though. For example, two of the most common types—superconducting qubits, which are often made of thin aluminum layers, and trapped-ion qubits, which use the energy levels of an ion’s electrons to represent 1s and 0s—must be kept at temperatures approaching absolute zero (–273 °C). Maintaining special refrigerators to keep them cool can be costly and difficult. And while researchers have made significant progress recently, both types of qubits have historically been difficult to connect into larger systems.

Eager to explore the potential of molecular qubits, Freedman has pioneered a unique “bottom-up” approach to creating them: She designs novel molecules with specific quantum properties to serve as qubits targeted for individual applications. Instead of focusing on a general goal such as maximizing coherence time (how long a qubit can preserve its quantum state), she begins by asking what kinds of properties are needed for, say, a sensor meant to measure biological phenomena at the molecular level. Then she and her team set out to create molecules that have these properties and are suitable for the environment where they’d be used.

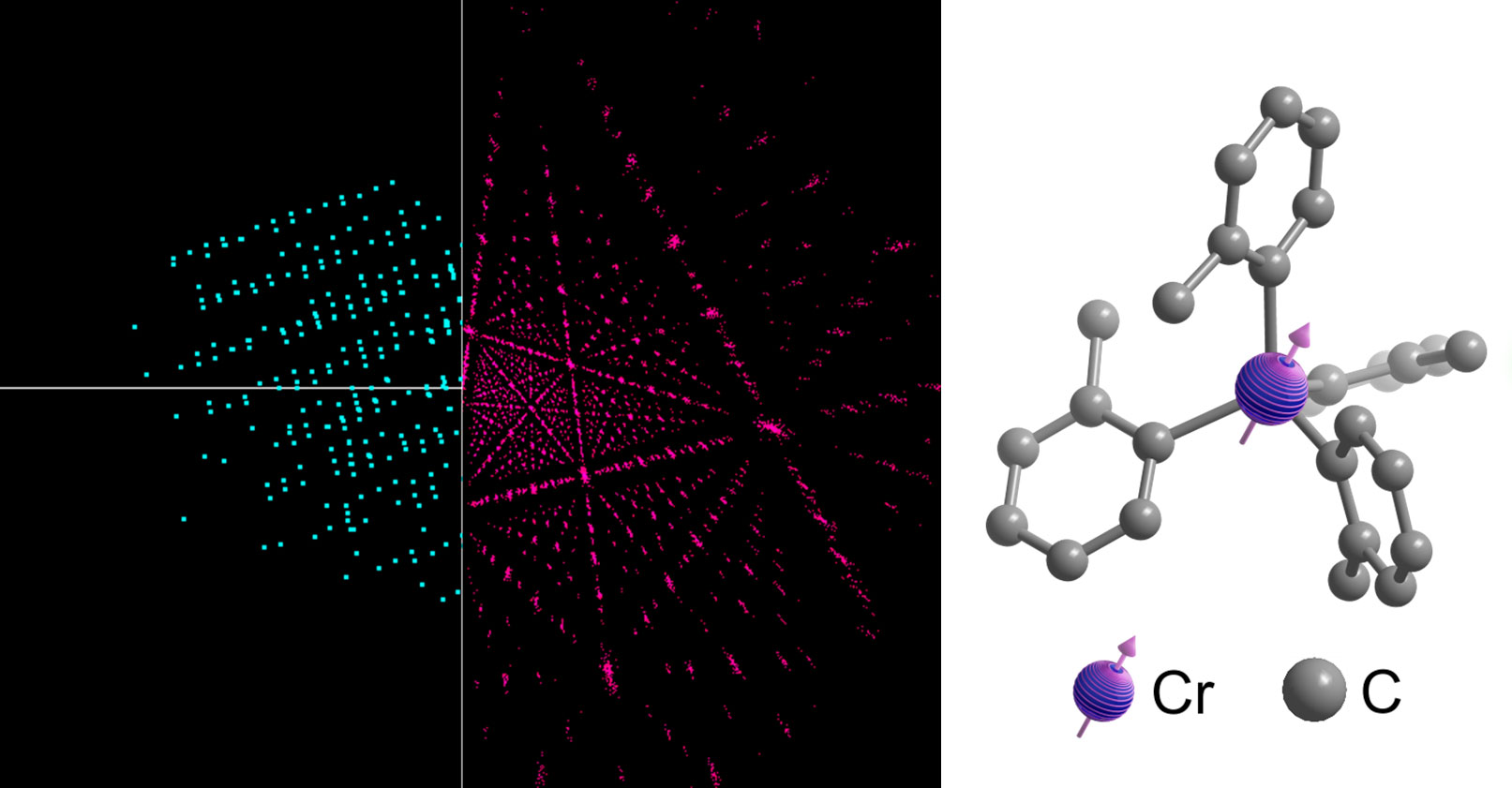

Made of a central metallic atom surrounded by hydrocarbon atoms, molecular qubits store information in their spin. The encoded information is later translated into photons, which are emitted to “read out” the information. These qubits can be tuned with laser precision—imagine adjusting a radio dial—by modifying the strength of the ligands, or bonds, connecting the hydrocarbons to the metal atom. These bonds act like tiny tuning forks; by adjusting their strength, the researchers can precisely control the qubit’s spin and the wavelength of the emitted photons. That emitted light can be used to provide information about atomic-level changes in electrical or magnetic fields.

While many researchers are eager to build reliable, scalable quantum computers, Freedman and her group devote most of their attention to developing custom molecules for quantum sensors. These ultrasensitive sensors contain particles in a state so delicately balanced that extremely small changes in their environments unbalance them, causing them to emit light differently. For example, one qubit designed in Freedman’s lab, made of a chromium atom surrounded by four hydrocarbon molecules, can be customized so that tiny changes in the strength of a nearby magnetic field will change its light emissions in a particular way.

A key benefit of using such molecules for sensing is that they are small enough—just a nanometer or so wide—to get extremely close to the thing they are sensing. That can offer an unprecedented level of precision when measuring something like the surface magnetism of two-dimensional materials, since the strength of a magnetic field decays with distance. A molecular quantum sensor “might not be more inherently accurate than a competing quantum sensor,” says Freedman, “but if you can lose an order of magnitude of distance, that can give us a lot of information.” Quantum sensors’ ability to detect electric or magnetic changes at the atomic level and make extraordinarily precise measurements could be useful in many fields, such as environmental monitoring, medical diagnostics, geolocation, and more.

When designing molecules to serve as quantum sensors, Freedman’s group also factors in the way they can be expected to act in a specific sensing environment. Creating a sensor for water, for example, requires a water-compatible molecule, and a sensor for use at very low temperatures requires molecules that are optimized to perform well in the cold. By custom-engineering molecules for different uses, the Freedman lab aims to make quantum technology more versatile and widely adaptable.

Embracing interdisciplinarity

As Freedman and her group focus on the highly specific work of designing custom molecules, she is keenly aware that tapping into the power of quantum science depends on the collective efforts of scientists from different fields.

“Quantum is a broad and heterogeneous field,” she says. She believes that attempts to define it narrowly hurt collective research—and that scientists must welcome collaboration when the research leads them beyond their own field. Even in the seemingly straightforward scenario of using a quantum computer to solve a chemistry problem, you would need a physicist to write a quantum algorithm, engineers and materials scientists to build the computer, and chemists to define the problem and identify how the quantum computer might solve it.

MIT’s collaborative environment has helped Freedman connect with researchers in different disciplines, which she says has been instrumental in advancing her research. She’s recently spoken with neurobiologists who proposed problems that quantum sensing could potentially solve and provided helpful context for building the sensors. Looking ahead, she’s excited about the potential applications of quantum science in many scientific fields. “MIT is such a great place to nucleate a lot of these connections,” she says.

“As quantum expands, there are so many of these threads which are inherently interdisciplinary,” she says.

Inside the lab

Freedman’s lab in Building 6 is a beehive of creativity and collaboration. Against a backdrop of colorful flasks and beakers, researchers work together to synthesize molecules, analyze their structures, and unlock the secrets hidden within their intricate atomic arrangements.

“We are making new molecules and putting them together atom by atom to discover whether they have the properties we want,” says Christian Oswood, a postdoctoral fellow.

Some sensitive molecules can only be made in the lab’s glove box, a nitrogen-filled transparent container that protects chemicals from oxygen and water in the ambient air. An example is an organometallic solution synthesized by one of Freedman’s graduate students, David Ullery, which takes the form of a vial of purple liquid. (“A lot of molecules have really pretty colors,” he says.)

Freedman is a passionate educator, dedicated to demystifying the complexities of chemistry for her students. Aware that many of them find the subject daunting, she strives to go beyond textbook equations.

Once synthesized, the molecules are taken to a single-crystal x-ray diffractometer a few floors below the Freedman lab. There, x-rays are directed at crystallized samples, and from the diffraction pattern, researchers can deduce their molecular structure—how the atoms connect. Studying the precise geometry of these synthesized molecules reveals how the structure affects their quantum properties, Oswood explains.

Researchers and students at the lab say Freedman’s cross-disciplinary outlook played a big role in drawing them to it. With a chemistry background and a special interest in physics, for example, Ullery joined because he was excited by the way Freedman’s research bridges those two fields.

Others echo this sentiment. “The opportunity to be in a field that’s both new and expanding like quantum science, and attacking it from this specific angle, was exciting to me both intellectually and professionally,” says Oswood.

Another graduate student, Cindy Serena Ngompe Massado, says she enjoys being part of the lab because she gets to collaborate with scientists in other fields. “It allows you to really approach scientific challenges in a more holistic and productive way,” she says.

Though the researchers spend most of their time synthesizing and analyzing molecules, fun infuses the lab too. Freedman checks in with everyone frequently, and conversations often drift beyond just science. She’s just as comfortable chatting about Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce as she is discussing research.

“Danna is very personable and very herself with us,” Ullery says. “It adds a bit of levity to being in an otherwise stressful grad school environment.”

Bringing textbook chemistry to life

In the classroom, Freedman is a passionate educator, dedicated to demystifying the complexities of chemistry for her students. Aware that many of them find the subject daunting, she strives to go beyond textbook equations.

For each lecture in her advanced inorganic chemistry classes, she introduces the “molecule of the day,” which is always connected to the lesson plan. When teaching about bimetallic molecules, for example, she showcased the potassium rubidium molecule, citing active research at Harvard aimed at entangling its nuclear spins. For a lecture on superconductors, she brought a sample of the superconducting material yttrium barium copper oxide that students could handle.

Chemistry students often think “This is painful” or “Why are we learning this?” Freedman says. Making the subject matter more tangible and showing its connection to ongoing research spark students’ interest and underscore the material’s relevance.

Freedman believes this is an exceptionally exciting time for budding chemists. She emphasizes the importance of curiosity and encourages them to ask questions. “There is a joy to being able to walk into any room and ask any question and extract all the knowledge that you can,” she says.

In her own research, she embodies this passion for the pursuit of knowledge, framing challenges as stepping stones to discovery. When she was a postdoc, her research on electron spins in synthetic materials hit what seemed to be a dead end that ultimately led to the discovery of a new class of magnetic material. So she tells her students that even the most difficult aspects of research are rewarding because they often lead to interesting findings.

That’s exactly what happened to Ullery. When he designed a molecule meant to be stable in air and water and emit light, he was surprised that it didn’t—and that threw a wrench into his plan to develop the molecule into a sensor that would emit light only under particular circumstances. So he worked with theoreticians in Giulia Galli’s group at the University of Chicago, developing new insights on what drives emission, and that led to the design of a new molecule that did emit light.

“Frustrating research is almost fun to deal with,” says Freedman, “even if it doesn’t always feel that way.”