Subtotal: 3.745,07€ (incl. VAT)

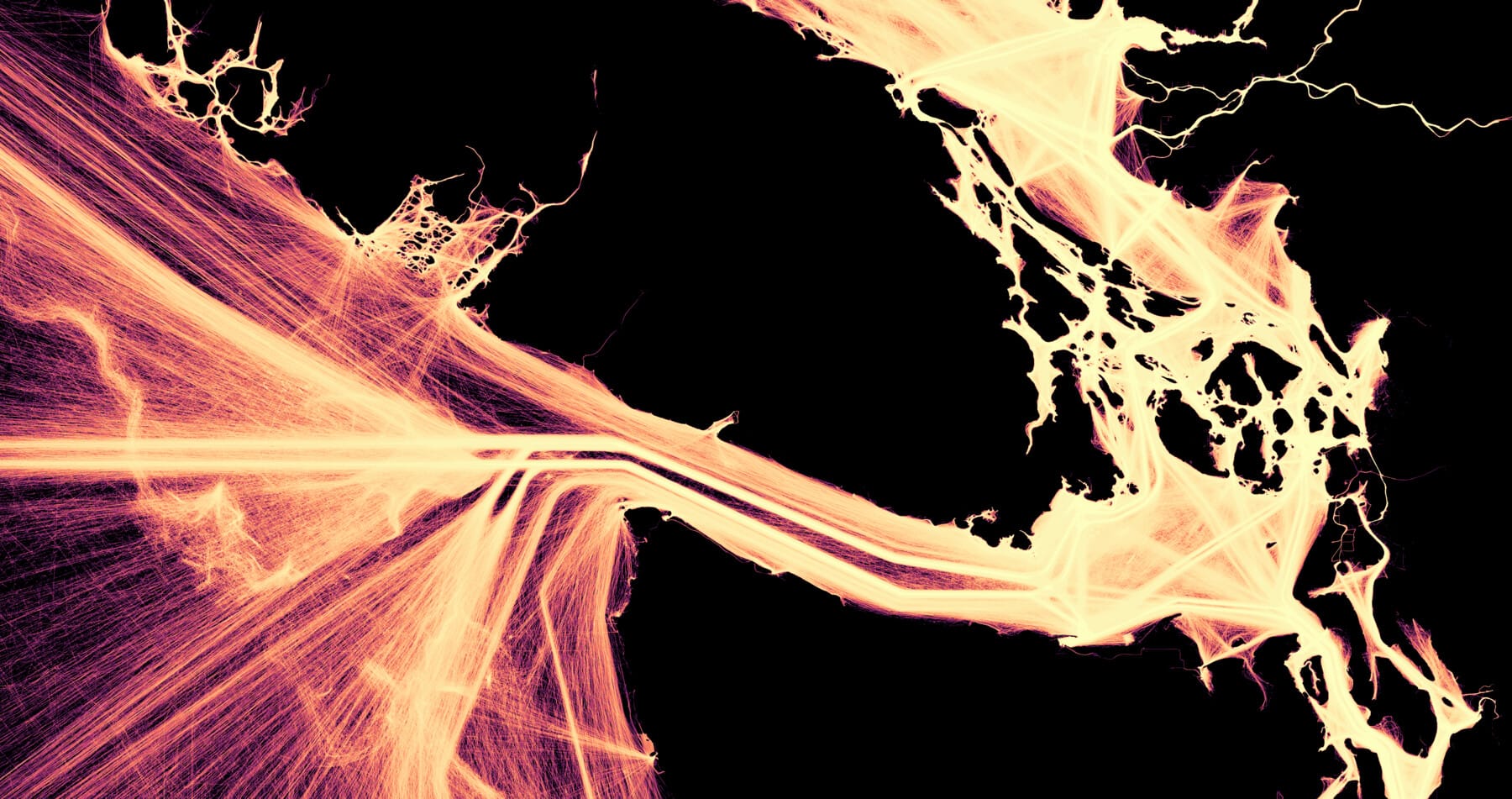

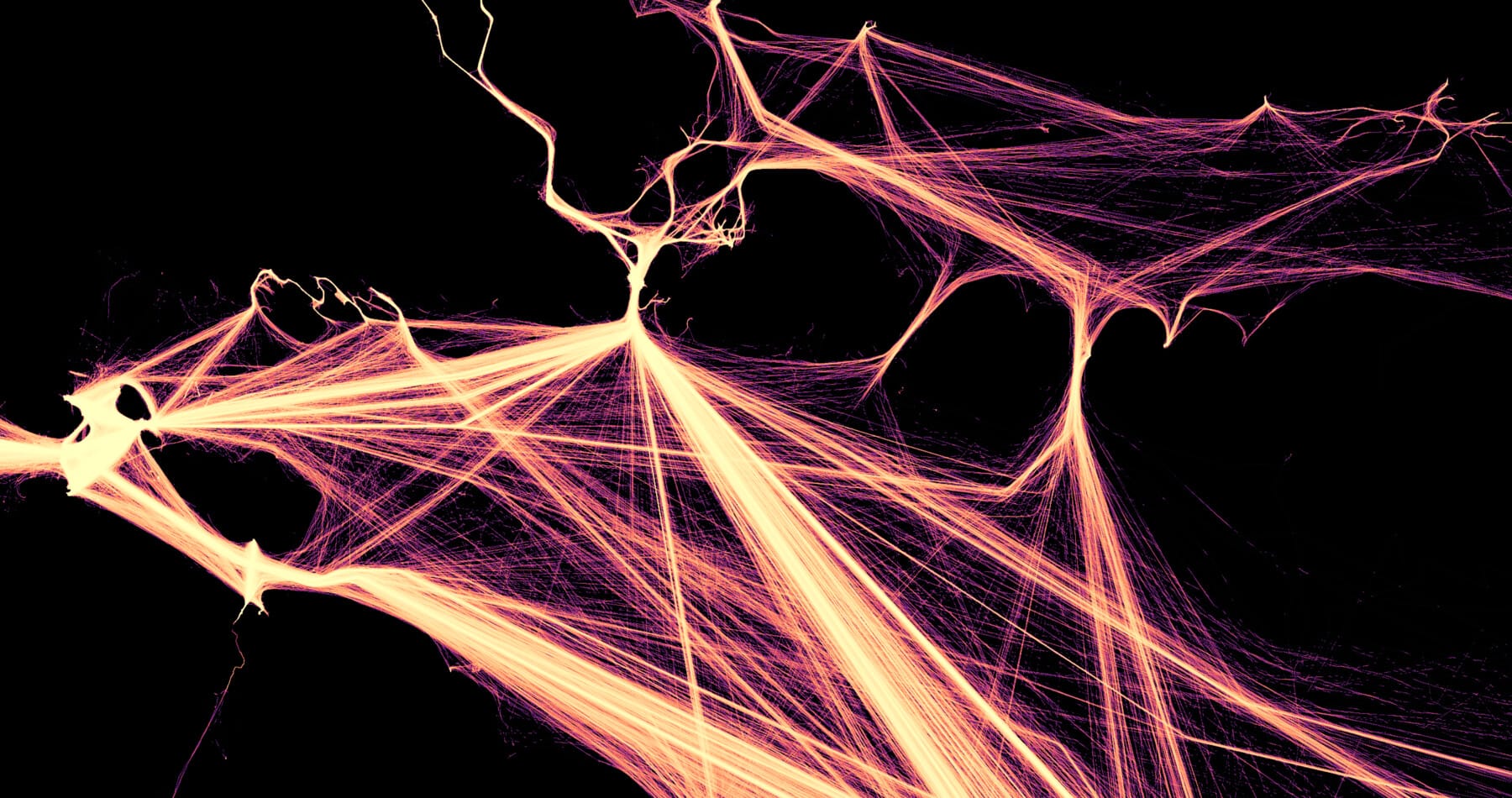

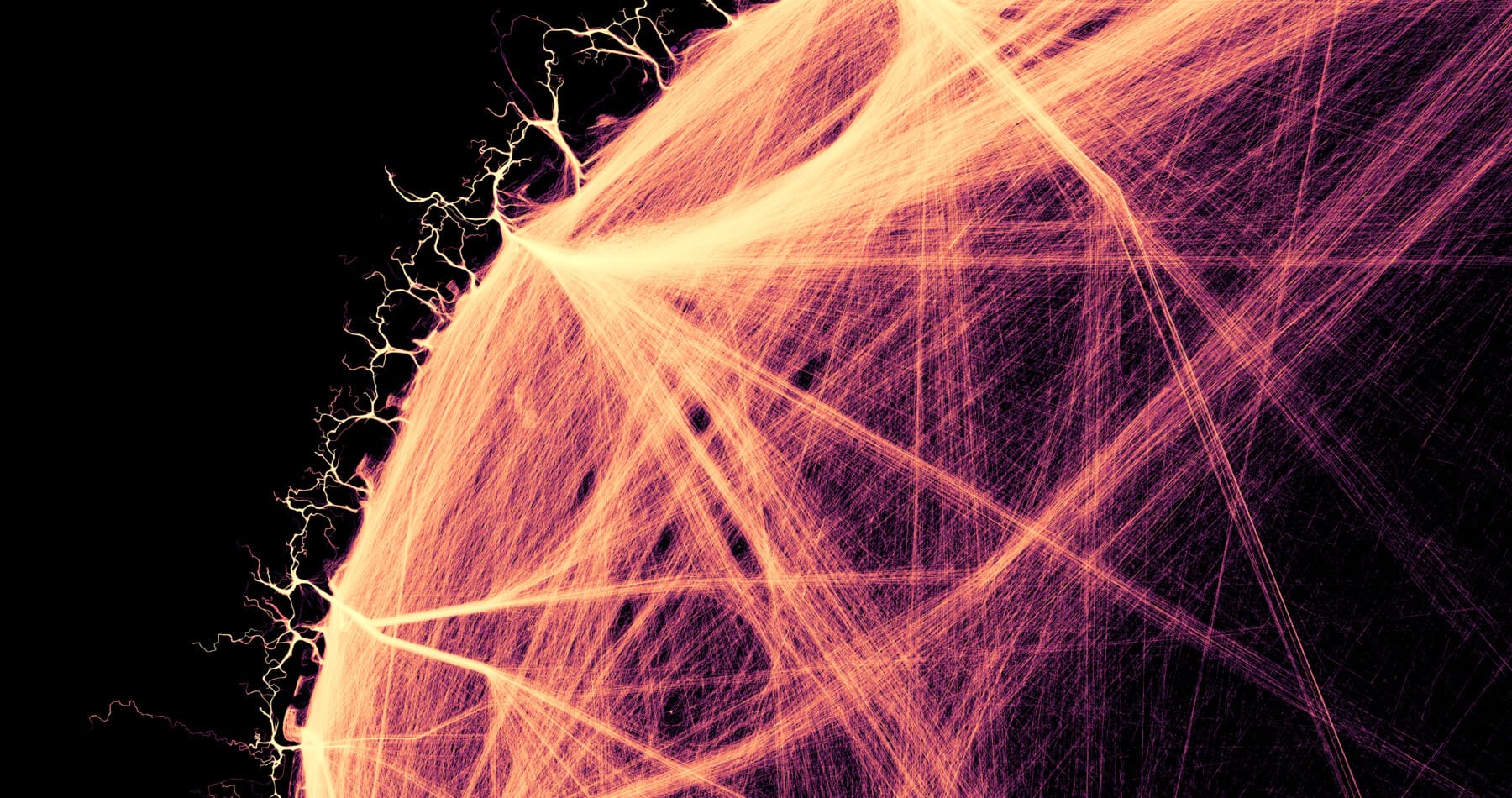

These stunning images trace ships’ routes as they move

As we run, drive, bike, and fly, we leave behind telltale marks of our movements on Earth—if you know where to look. Physical tracks, thermal signatures, and chemical traces can reveal where we’ve been. But another type of trail we leave comes from the radio signals emitted by the cars, planes, trains, and boats we use.

On airplanes, technology called ADS-B (Automatic Dependent Surveillance–Broadcast) provides real-time location, identification, speed, and orientation data. For ships at sea, that function is performed by the AIS (Automatic Identification System).

Operating at 161.975 and 162.025 megahertz, AIS transmitters broadcast a ship’s identification number, name, call sign, length and beam, type, and antenna location every six minutes. Ship location, position time stamp, and direction are transmitted more frequently. The primary purpose of AIS is maritime safety—it helps prevent collisions, assists in rescues, and provides insight into the impact of ship traffic on marine life. US Coast Guard regulations say that generally, private boats under 65 feet in length are not required to use AIS, but most commercial vessels are. Unlike ADS-B in planes, AIS can be turned off only in rare circumstances.

A variety of sectors use AIS data for many different applications, including monitoring ship traffic to avoid disruption of undersea internet cables, identifying whale strikes, and studying the footprint of underwater noise.

Using the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association’s Marine Cadastre tool, you can download 16 years of detailed daily ship movements, as well as “transit count” maps generated from a year’s worth of data showing each ship’s accumulated paths. The data is collected entirely from ground-based stations along the US coasts.

I downloaded all of 2023’s transit count maps and loaded them up in geographic information system software called QGIS to visualize this year of marine traffic.

The maps are abstract and electric. With landmasses removed, the ship traces resemble long-exposure photos of sparklers, high-energy particle collisions, or strands of fiber-optic wire.

DATA: NOAA; MAP: JON KEEGAN / BEAUTIFUL PUBLIC DATA

DATA: NOAA; MAP: JON KEEGAN / BEAUTIFUL PUBLIC DATA

DATA: NOAA; MAP: JON KEEGAN / BEAUTIFUL PUBLIC DATA

DATA: NOAA; MAP: JON KEEGAN / BEAUTIFUL PUBLIC DATA

Zooming in on these maps, you might see strange geometric patterns of perfect circles, or lines in a grid. Some of these are fishing grounds, others are scientific surveys mapping the seafloor, and others represent boats going to and from offshore oil rigs, especially off Louisiana’s gulf coast.

Hiding in plain sight

Having a global, near-real-time system for tracking the precise movements of all ships at sea sounds like a great innovation—unless you’re trying to keep your ships’ movements and cargoes secret.

In 2023, Bloomberg investigated how Russia evaded sanctions on its oil exports after the invasion of Ukraine by “spoofing”—transmitting fake AIS data—to mislead observers. Tracking a fleet of rusting ships of questionable seaworthiness, reporters compared AIS data with what they actually saw on the sea—and discovered that the ships weren’t where the data said they were.

Monitoring the fishing industry

Clusters of fishing vessels gravitating toward known fishing grounds create some of the most interesting patterns on the maps.

Global Fishing Watch is an international nonprofit that uses AIS to monitor the fishing industry, seeking to protect marine life from overfishing. But it says that only 2% of fishing vessels use AIS transmitters.

The organization, which is backed by Google, the ocean conservation group Oceana, and the satellite imagery company SkyTruth, combines AIS data with satellite imagery and uses machine learning to classify the types of fishing technology being used.

In a press release announcing the creation of Global Fishing Watch, John Amos, the president and founder of SkyTruth, said: “So much of what happens out on the high seas is invisible, and that has been a huge barrier to understanding and showing the world what’s at stake for the ocean.”

A version of this story appeared in Beautiful Public Data (beautifulpublicdata.com), a newsletter that curates visually interesting datasets collected by government agencies.