Subtotal: 1.849,24€ (incl. VAT)

The Renaissance man from Port Gamble Bay

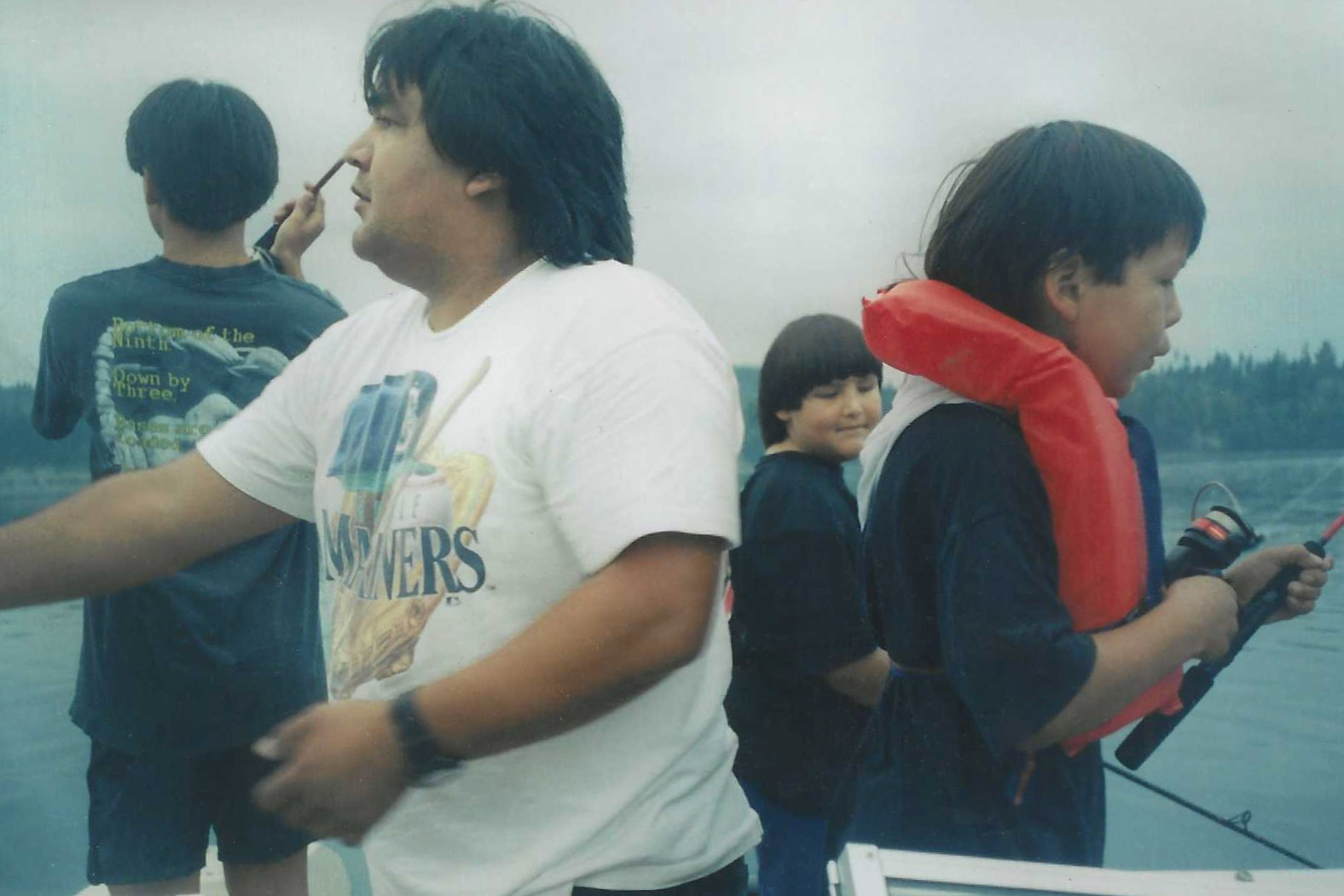

When Anthony Jones ’08 reminisces about his childhood, he thinks of clams. Growing up on the reservation of the Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe, about an hour from Seattle, he spent a lot of time playing outside with his brothers—fishing, digging clams, and gathering oysters on the beach.

Those idyllic childhood memories wouldn’t have been possible, though, if not for a legal fight that happened before Jones was born—a case that in some ways paved the way for his own career as a lawyer.

The Port Gamble S’Klallam Tribe signed a treaty with the US government in 1855 that ceded the vast majority of their historic territories but left them rights to access traditional food sources, especially fish. But for years the Washington state government didn’t honor those rights, leading to large-scale protests during the civil rights era by the S’Klallam (whose historical name means “the strong people”) and other tribes. Finally, thanks to a landmark 1974 decision in a federal lawsuit, the federal government compelled the state to recognize them.

“Growing up as I did in a Native American community, I was aware of the struggle that my community had gone through to have their rights vindicated,” Jones says. That history left him with a “deep sense of justice,” which is part of what pushed him toward law as an adult.

These days, he practices a unique combination of Native law and patent law, the latter of which draws from his background as a mechanical engineering student at MIT and his “tendency to tinker.” Though his two primary practice areas remain largely separate, his willingness to follow his passions as a young man set him on the path that allows him to do both.

As a teenager, when Jones wasn’t on the beach, he was learning to play electric guitar—or learning how to take one apart. While other kids his age might have focused on memorizing chords, he found himself more interested in how the instrument worked, trying to understand circuit diagrams and the role of the potentiometer, the electrical component that helps make volume knobs work. That helped him land at the Summer Science Program at New Mexico Tech, just south of Albuquerque, before his senior year of high school.

The program, which focused on astrophysics, helped set the stage for Jones’s next step. “It felt like the first time that I was around kids who had similar interests to mine,” he says. He loved the atmosphere, and the experience convinced him to apply to MIT, where he enrolled a year later.

The move from Port Gamble to Cambridge was tough at times—there was the culture shock of transitioning from the Pacific Northwest to the Northeast and from life in a rural community to one near a bustling metropolis like Boston, not to mention the relative lack of Native students and faculty on campus and the challenging academics. “It was not an easy adjustment, but I learned a lot from it,” Jones says. “It was invigorating in many ways, and challenging for many of the same reasons.”

COURTESY OF ANTHONY JONES

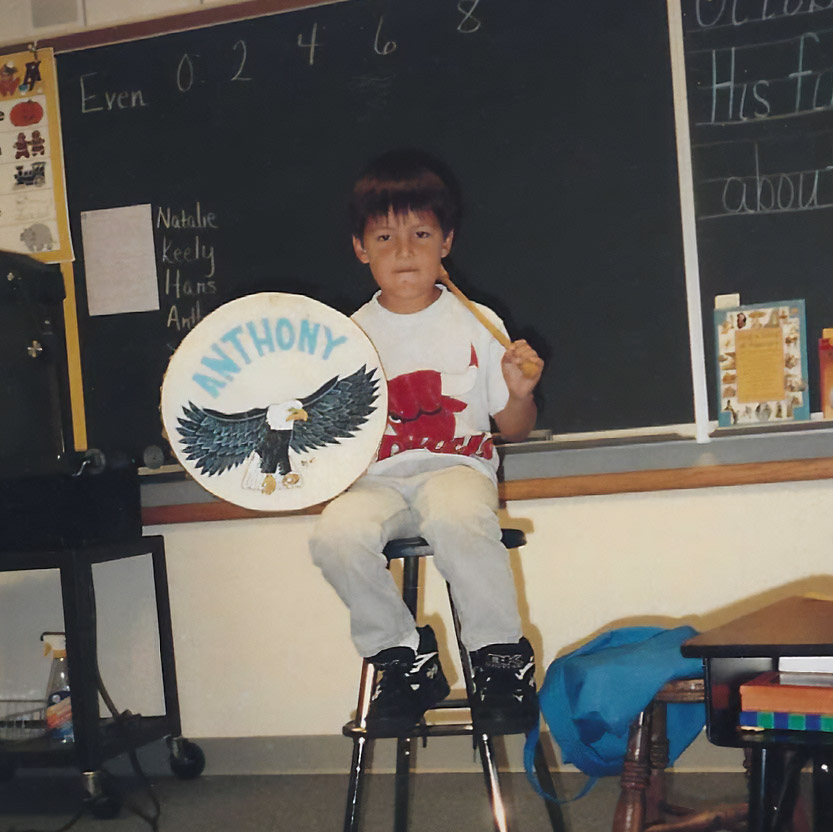

COURTESY OF ANTHONY JONES

As he found his footing, he also began to find outlets for his diverse skills. He remembers hands-on classes, like a robotics competition course, as highlights that let him indulge his innate curiosity. Jones was also part of the first class to complete the undergraduate business minor that the Sloan School of Management had just started offering.

“It was very different from the STEM stuff I was studying in my major program—counterbalancing the technology focus with more of a human focus. It was about understanding negotiation and how businesses operate,” he says. “I enjoyed that quite a bit.”

Realizing how much he liked working on the “human side” of things, and with his tribe’s legal rights in mind, Jones decided to go to law school after graduating from MIT in 2008. He enrolled at Washington University in St. Louis, where he studied, among other things, tribal governance and federal Native American law, an area of practice that requires specialized expertise.

“It’s not as simple as taking your knowledge of state and federal law and just transferring that to another setting. There’s a big learning curve,” he says. “Plus, there are over 500 Native American tribes in the United States, and each of them has its own culture, history, and language.” But Jones was willing to put in the extra work, explaining, “It’s very helpful to have somebody who comes from these communities to be able to be an advocate for a Native American tribe.”

As soon as he finished law school, he was offered a job as an in-house attorney for the Tulalip Tribes, focusing on tribal governance, economic development, and tribal court litigation. “It was rewarding to use my legal advocacy skills while also helping them advocate in a very cultural way,” he says, noting that while working with the tribe he was able to transition fluidly between drum ceremonies and the courtroom. Mike Taylor, the lawyer who recruited him for the job and who worked with him for six or seven years before his retirement, describes Jones as working quickly, quietly, and “meticulously” on behalf of the Tulalip.

A young Jones holds his first hand drum, which his great-uncle made for him. Jones made the white raven drum (right) for his daughter.

Not long after starting the job, Jones moved home to the Port Gamble reservation on the Kitsap Peninsula, and Taylor remembers being struck by the dedication to his community that the decision symbolized. In order to get to work, he had to drive to the ferry terminal, take a half-hour-long ferry ride, and then drive another 45 minutes to the Tulalip reservation.

After almost nine years working for the Tulalip, Jones decided it was time to start using his engineering background again, and he set his sights on a job focused more on intellectual-property law.

To win such a position, he would have to sit for the patent bar exam, which many people take classes to prepare for. But besides his full-time job, Jones had a family with young kids, so he didn’t think he could spare the money or the time for a course. He ordered a 10-years-out-of-date study manual from eBay and began updating and studying it in his spare time.

His hard work paid off, and after passing the patent bar, he was able to land his first job in patent law, where he stayed for two years before switching to his current firm, Dorsey & Whitney. There, he’s been able to find a balance between his two primary areas of expertise: Dorsey & Whitney not only practices patent law but was “basically the first full-service large law firm to start practicing Native American law back in the ’80s,” he says.

In between his work and his family life, Jones has also found time to make art that honors and carries forward his tribe’s cultural legacy.

“The experience of moving away for college and law school and then coming back to my community gave me a greater appreciation for what was unique about my upbringing and the place that I came from,” he says. “So I started studying the culture and the history of Northwest Native people, and that led me to also study the material culture—the artwork, the artifacts, things like that.”

CHONA KASINGER

It didn’t take long before his tinkering instinct kicked back in, and he found himself trying to figure out how to make the things he was studying, whether they were drums or canoes. He also sought out chances to learn from other experts nearby.

Though he’d never thought himself artistically inclined, his creations suggest otherwise. Today, his thunderbird design adorns a Washington state ferry; a drum he emblazoned with a killer whale resides at the offices of Earthjustice, an environmental nonprofit focused on legal advocacy; and a glass sculpture representing a stylized human figure of larger-than-life proportions that he collaborated on with three other artists (one of whom is a cousin) stands proudly in Seattle’s Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture.

In many ways the instincts that animate the art, the commitment to his community, and his professional life all emanate from the same place. “I would not have been able to predict all of the interesting things I’ve been able to do,” Jones says. “I’ve just been open to a variety of experiences and been ready to go when these opportunities arise.”