Subtotal: 194,45€ (incl. VAT)

Tech that measures our brainwaves is 100 years old. How will we be using it 100 years from now?

This article first appeared in The Checkup, MIT Technology Review’s weekly biotech newsletter. To receive it in your inbox every Thursday, and read articles like this first, sign up here.

This week, we’re acknowledging a special birthday. It’s 100 years since EEG (electroencephalography) was first used to measure electrical activity in a person’s brain. The finding was revolutionary. It helped people understand that epilepsy was a neurological disorder as opposed to a personality trait, for one thing (yes, really).

The fundamentals of EEG have not changed much over the last century—scientists and doctors still put electrodes on people’s heads to try to work out what’s going on inside their brains. But we’ve been able to do a lot more with the information that’s collected.

We’ve been able to use EEG to learn more about how we think, remember, and solve problems. EEG has been used to diagnose brain and hearing disorders, explore how conscious a person might be, and even allow people to control devices like computers, wheelchairs, and drones.

But an anniversary is a good time to think about the future. You might have noticed that my colleagues and I are currently celebrating 125 years of MIT Technology Review by pondering the technologies the next 125 years might bring. What will EEG allow us to do 100 years from now?

First, a quick overview of what EEG is and how it works. EEG involves placing electrodes on the top of someone’s head, collecting electrical signals from brainwaves, and feeding these to a computer for analysis. Today’s devices often resemble swimming caps. They’re very cheap compared with other types of brain imaging technologies, such as fMRI scanners, and they’re pretty small and portable.

The first person to use EEG in people was Hans Berger, a German psychiatrist who was fascinated by the idea of telepathy. Berger developed EEG as a tool to measure “psychic energy,” and he carried out his early research—much of it on his teenage son—in secret, says Faisal Mushtaq, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Leeds in the UK. Berger was, and remains, a controversial figure owing to his unclear links with Nazi regime, Mushtaq tells me.

But EEG went on to take the neuroscience world by storm. It has become a staple of neuroscience labs, where it can be used on people of all ages, even newborns. Neuroscientists use EEG to explore how babies learn and think, and even what makes them laugh. In my own reporting, I’ve covered the use of EEG to understand the phenomenon of lucid dreaming, to reveal how our memories are filed away during sleep, and to allow people to turn on the TV by thought alone.

EEG can also serve as a portal into the minds of people who are otherwise unable to communicate. It has been used to find signs of consciousness in people with unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (previously called a “vegetative state”). The technology has also allowed people paralyzed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) to communicate by thought and tell their family members they are happy.

So where do we go from here? Mushtaq, along with Pedro Valdes-Sosa at the University of Electronic Science and Technology of China in Chengdu and their colleagues, put the question to 500 people who work with EEG, including neuroscientists, clinical neurophysiologists, and brain surgeons. Specifically, with the help of ChatGPT, the team generated a list of predictions, which ranged from the very likely to the somewhat fanciful. Each of the 500 survey responders was asked to estimate when, if at all, each prediction might be likely to pan out.

Some of the soonest breakthroughs will be in sleep analysis, according to the responders. EEG is already used to diagnose and monitor sleep disorders—but this is set to become routine practice in the next decade. Consumer EEG is also likely to take off in the near future, potentially giving many of us the opportunity to learn more about our own brain activity, and how it corresponds with our wellbeing. “Perhaps it’s integrated into a sort of baseball cap that you wear as you walk around, and it’s connected to your smartphone,” says Mushtaq. EEG caps like these have already been trialed on employees in China and used to monitor fatigue in truck drivers and mining workers, for example.

For the time being, EEG communication is limited to the lab or hospital, where studies focus on the technology’s potential to help people who are paralyzed, or who have disorders of consciousness. But that is likely to change in the coming years, once more clinical trials have been completed. Survey respondents think that EEG could become a primary tool of communication for individuals like these in the next 20 years or so.

At the other end of the scale is what Mushtaq calls the “more fanciful” application—the idea of using EEG to read people’s thoughts, memories, and even dreams.

Mushtaq thinks this is a “relatively crazy” prediction—one that’s a long, long way from coming to pass considering we don’t yet have a clear picture of how and where our memories are formed. But it’s not completely science fiction, and some respondents predict the technology could be with us in around 60 years.

Artificial intelligence will probably help neuroscientists squeeze more information from EEG recordings by identifying hidden patterns in brain activity. And it is already being used to turn a person’s thoughts into written words, albeit with limited accuracy. “We’re on the precipice of this AI revolution,” says Mushtaq.

These kinds of advances will raise questions over our right to mental privacy and how we can protect our thoughts. I talked this over with Nita Farahany, a futurist and legal ethicist at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, last year. She told me that while brain data itself is not thought, it can be used to make inferences about what a person is thinking or feeling. “The only person who has access to your brain data right now is you, and it is only analyzed in the internal software of your mind,” she said. “But once you put a device on your head … you’re immediately sharing that data with whoever the device manufacturer is, and whoever is offering the platform.”

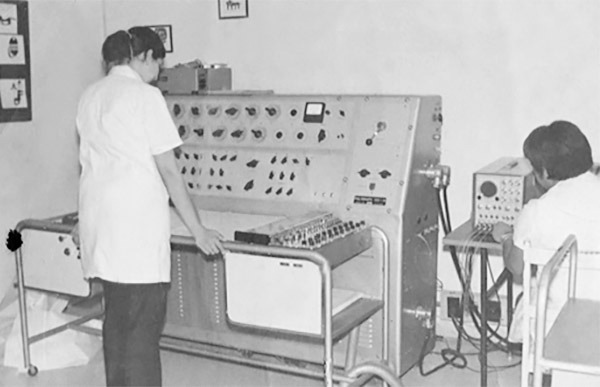

Valdes-Sosa is optimistic about the future of EEG. Its low cost, portability, and ease of use make the technology a prime candidate for use in poor countries with limited resources, he says; he has been using it in his research since 1969. (You can see what his set up looked like in 1970 in the image below!) EEG should be used to monitor and improve brain health around the world, he says: “It’s difficult … but I think it could happen in the future.”

PEDRO VALDES-SOSA

Now read the rest of The Checkup

Read more from MIT Technology Review’s archive

You can read the full interview with Nita Farahany, in which she describes some decidedly creepy uses of brain data, here.

Ross Compton’s heart data was used against him when he was accused of burning down his home in Ohio in 2016. Brain data could be used in a similar way. One person has already had to hand over recordings from a brain implant to law enforcement officials after being accused of assaulting a police officer. (It turned out that person was actually having a seizure at the time.) I looked at some of the other ways your brain data could be used against you in a previous edition of The Checkup.

Teeny-tiny versions of EEG caps have been used to measure electrical activity in brain organoids (clumps of neurons that are meant to represent a full brain), as my colleague Rhiannon Williams reported a couple of years ago.

EEG has also been used to create a “brain-to-brain network” that allows three people to collaborate on a game of Tetris by thought alone.

Some neuroscientists are using EEG to search for signs of consciousness in people who seem completely unresponsive. One team found such signs in a 21-year-old woman who had experienced a traumatic brain injury. “Every clinical diagnostic test, experimental and established, showed no signs of consciousness,” her neurophysiologist told MIT Technology Review. After a test that involved EEG found signs of consciousness, the neurophysiologist told rehabilitation staff to “search everywhere and find her!” They did, about a month later. With physical and drug therapy, she learned to move her fingers to answer simple questions.

From around the web

Food waste is a problem. This Japanese company is fermenting it to create sustainable animal feed. In case you were wondering, the food processing plant smells like a smoothie, and the feed itself tastes like sour yogurt. (BBC Future)

The pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences is accused of “patent hopping”—having dragged its feet to bring a safer HIV treatment to market while thousands of people took a harmful one. The company should be held accountable, argues a cofounder of PrEP4All, an advocacy organization promoting a national HIV prevention plan. (STAT)

Anti-suicide nets under San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge are already saving lives, perhaps by acting as a deterrent. (The San Francisco Standard)

Genetic screening of newborn babies could help identify treatable diseases early in life. Should every baby be screened as part of a national program? (Nature Medicine)

Is “race science”—which, it’s worth pointing out, is nothing but pseudoscience—on the rise, again? The far right’s references to race and IQ make it seem that way. (The Atlantic)

As part of our upcoming magazine issue celebrating 125 years of MIT Technology Review and looking ahead to the next 125, my colleague Antonio Regalado explores how the gene-editing tool CRISPR might influence the future of human evolution. (MIT Technology Review)