Subtotal: 115,56€ (incl. VAT)

Rio de Janeiro is making a digital map of one of Brazil’s largest favelas

Finding your way through Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro is not easy. The buildings are densely and turbulently arranged in a manner that defies traditional identification systems like street names and numbers. Rocinha is a favela, one of the largest among hundreds of unplanned settlements that have sprung up on the outskirts of Brazilian cities since the 19th century. More than 5% of the country’s population now lives in communities like these, with 100,000 people in Rocinha alone.

The challenge of navigating Rocinha has birthed creative solutions, such as the “friendly mailman” program: companies deliver parcels to a central drop-off point, and a team of Rocinha residents—the only couriers familiar enough with the area to navigate its maze-like streets—take them the rest of the way.

With little formal aid or administration and scant economic opportunities, favela residents have struggled to contend with unhealthy living conditions and frequent violence. A thick wall of social segregation means that resources from the city—including electricity and clean water—must take twisting, uncertain paths to make it inside. Life expectancy in favelas is just 48, which is 20 years below the national average.

Much has been made of the dizzying growth of the world’s cities, but few people are aware of what most urban growth actually looks like. Births and migrations are concentrated in the developing world, and with the exception of China, most new urban fabric is informal—more shantytowns than skyscrapers. For all our futuristic reveries, the city of tomorrow probably will not look much different from Rocinha.

In the 20th century, the Brazilian government attempted to eradicate favelas and replace them with more formal public housing, but the bulldozers could not keep up with the massive urban migration that made these settlements swell.

For all our futuristic reveries, the city of tomorrow probably will not look much different from Rocinha.

Other governments and urban planners have also tried to prevent such settlements from forming or to dismantle them when they do, but that’s proved a losing strategy. More than 2 billion people worldwide are now estimated to live in them.

In the early 2000s, the city of Medellín, Colombia, started a reckoning process that would inspire the world. Settlements had taken shape in the mountains, and the city committed to serving these communities as it would any other. It began by constructing a network of cable cars, soaring above the terrain that had long divided the city.

Efforts to eradicate these communities gave way to incorporation; the government chose them as the sites for new libraries and public parks. The Medellín model, despite some shortcomings, has since become the gold standard in Latin America and around the world.

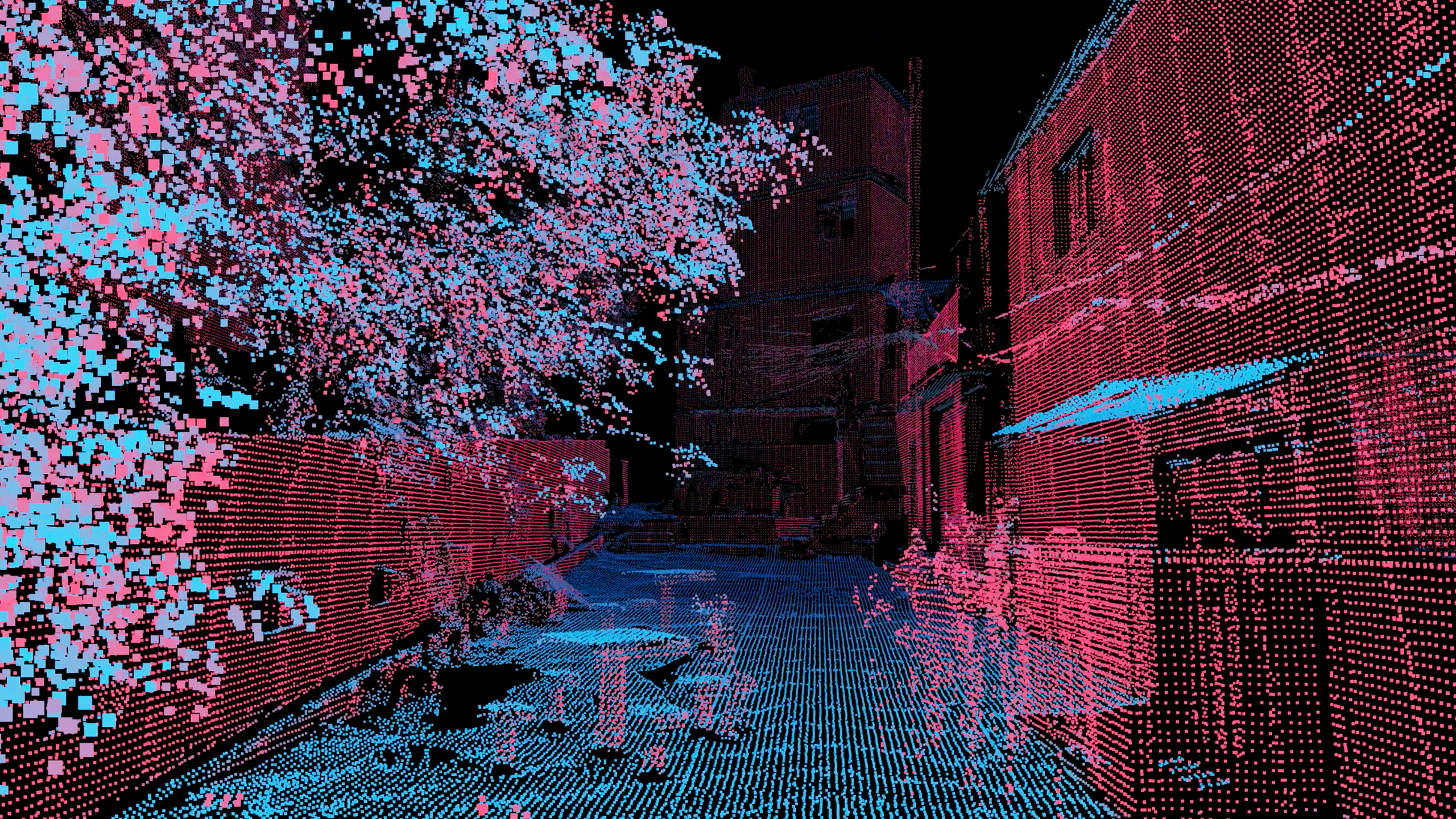

Twenty years after Medellín began to take this innovative approach, new technology is equipping us with an even more powerful set of tools. Today, the city of Rio de Janeiro and MIT’s Senseable City Lab are working together to digitally map the entirety of Rocinha for the first time.

Researchers on our team are carrying 3D scanners through the narrow alleys and down the sloping hills, hoping to capture every inch of the 1.5-square-kilometer neighborhood. Around 300,000 data points are generated every second.

FÁBIO DUARTE

The cost to scan the entire community of Rocinha will be less than $60,000, which we believe will more than pay for itself by enabling useful applications for its residents. With an accurate map of Rocinha, the city could more easily provide access to public services such as water and waste collection, improve alleyways, and create plazas and public places.

These scans could also be used to create property records, which could be managed and traded on a blockchain to avoid bureaucracy and reduce the cost of transferring titles. We acknowledge that building such a system from 3D scans may raise concerns about data privacy. If we’re able to address those, though, favela residents could buy and sell property more easily than on any formal property registry systems.

Having better knowledge of the favelas’ physical layout could also improve living conditions. Urban designers could use this data to decide where to install stairs, or what structures to remove to allow in more air, sun, or light.

It’s worth recalling that most cities were born from informality.

Clearly, the long-term solution to the most pressing problems favela residents face is to address the social issues that lead these settlements to be built in the first place. Every nation has its own challenges. Brazil must reduce social inequality, Western Europe must rethink immigration from its former colonies, and nations everywhere should prepare for an uptick in climate-related migration.

How we choose to respond to favelas, shantytowns, and refugee camps over the next few years will define the political and cultural attitudes that determine their long-term future. It’s worth recalling, then, that most cities were born from informality.

Many parts of Paris were this way until the interventions of Baron Haussmann, whose 19th-century redesign was made possible with the force of a military strongman. Fifty years ago, Singapore was still a city of shantytowns. New York once had more illegal settlements than anywhere else in the US, but waves of gentrification have allowed us to forget that messy history.

The road to the city of tomorrow runs through Rocinha. Our decisions in this generation—to ignore, eradicate, or integrate—will help decide the destinies of unborn billions in the years to come. Favela residents are already experts in managing informality—some were mapping their communities with pen and paper long before we began our work with 3D scanners. Working alongside them, we can find a new balance between the top-down and bottom-up forces that have shaped cities since their origin.

Fábio Duarte and Carlo Ratti are researchers at the MIT Senseable City Lab. Washington Fajardo is the secretary of urban planning at the City of Rio de Janeiro.