Inside the software that will become the next battle front in US-China chip war

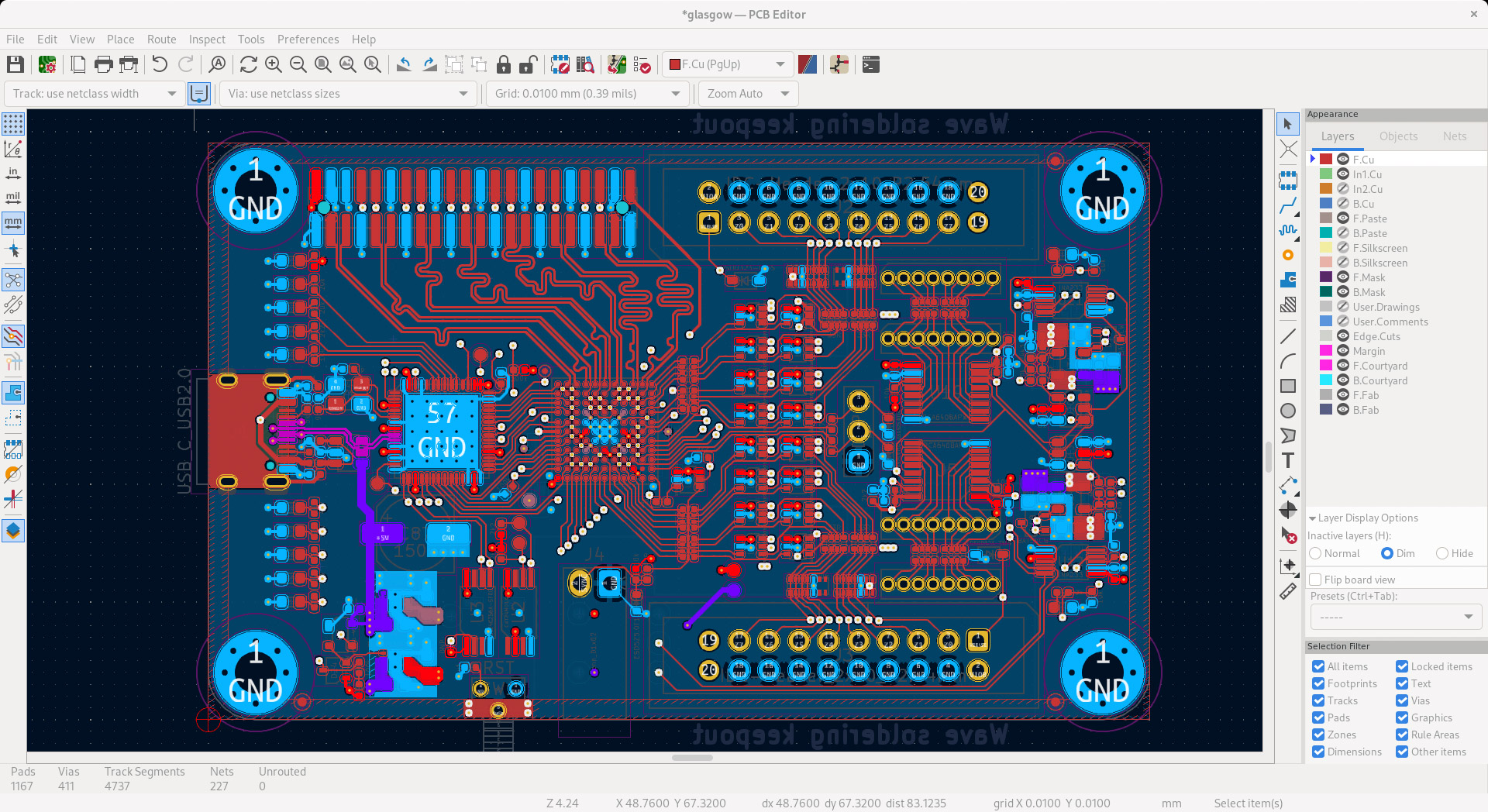

The days when computer chips were designed by hand are long gone. Where chips contained thousands of transistors in the 1970s, they have more than a hundred billion today, and it’s impossible to create these designs manually. That’s where electronic design automation (EDA) software comes in. It’s a category of tools that help electrical engineers design and develop ever more complex chips.

This software now forms the latest battle front in the tech trade war between China and the United States. On August 12, the US Commerce Department announced a multilateral export control on certain EDA tools, blocking China and over 150 other countries—essentially any country that isn’t a traditional US ally—from accessing them without specially granted licenses.

EDA software is a small but mighty part of the semiconductor supply chain, and it’s mostly controlled by three Western companies. That gives the US a powerful point of leverage, similar to the way it wanted to restrict access to lithography machines—another crucial tool for chipmaking—last month. So how has the industry become so American-centric, and why can’t China just develop its own alternative software?

What is EDA?

Electronic design automation (also known as electronic computer-aided design, or ECAD) is the specialized software used in chipmaking. It’s like the CAD software that architects use, except it’s more sophisticated, since it deals with billions of minuscule transistors on an integrated circuit.

There’s no single dominant software program that represents the best in the industry. Instead, a series of software modules are often used throughout the whole design flow: logic design, debugging, component placement, wire routing, optimization of time and power consumption, verification, and more. Because modern-day chips are so complex, each step requires a different software tool.

How important is EDA to chipmaking?

Although the global EDA market was valued at only around $10 billion in 2021, making it a small fraction of the $595 billion semiconductor market, it’s of unique importance to the entire supply chain.

The semiconductor ecosystem today can be seen as a triangle, says Mike Demler, a consultant who has been in the chip design and EDA industry for over 40 years. On one corner are the foundries, or chip manufacturers like TSMC; on another corner are intellectual-property companies like ARM, which make and sell reusable design units or layouts; and on the third corner are the EDA tools. All three together make sure the supply chain moves smoothly.

From the name, it may sound as if EDA tools are only important to chip design firms, but they are also used by chip manufacturers to verify that a design is feasible before production. There’s no way for a foundry to make a single chip as a prototype; it has to invest in months of time and production, and each time, hundreds of chips are fabricated on the same semiconductor base. It would be an enormous waste if they were found to have design flaws. Therefore, manufacturers rely on a special type of EDA tool to do their own validation.

What are the leading companies in the EDA industry?

There are only a few companies that sell software for each step of the chipmaking process, and they have dominated this market for decades. The top three companies—Cadence (American), Synopsys (American), and Mentor Graphics (American but acquired by the German company Siemens in 2017)—control about 70% of the global EDA market. Their dominance is so strong that many EDA startups specialize in one niche use and then sell themselves to one of these three companies, further cementing the oligopoly.

What is the US government doing to restrict EDA exports to China?

US companies’ outsize influence on the EDA industry makes it easy for the US government to squeeze China’s access. In its latest announcement, it pledged to add certain EDA tools to its list of technologies banned from export. The US will coordinate with 41 other countries, including Germany, to implement these restrictions.

The restricted tools are those that can be used for GAAFET (gate-all-around field-effect transistor) architecture, the most advanced circuit structure today, which is critical to making the latest chips and more advanced ones in the future. The Commerce Department is still seeking public comment to identify which EDA software is most helpful in achieving this specific structure and therefore should be added to the list.

Chinese hardware giant Huawei was similarly restricted in 2019, losing access to all US EDA tools, and the Biden administration has continued the Trump administration’s preference for export controls as a trade war weapon. “Their previous round of restrictions on Huawei was so successful [that] they found this to be the track to pursue,” says Xiaomeng Lu, an analyst at the consultancy firm Eurasia Group.

How will China be affected?

In the short term China won’t be that badly affected, because Chinese foundries are not advanced enough to make the state-of-the-art chips that need the GAAFET structure. But the blockade means Chinese chip design firms won’t be able to access the most advanced tools, and as time passes, they’ll most likely fall behind.

However, blocking the export of software is very different from blocking the export of bulky hardware like lithography machines, which are impossible to smuggle into China because they are so traceable. EDA software tools are distributed online, so they can be pirated.

Chinese companies could either hold on to the EDA software they have already purchased or resort to hacking licenses or acquiring them through shadow entities. That makes it harder to predict how effective this latest round of restrictions will be.

What is China doing regarding EDA?

China has slowly realized that it needs to develop domestic alternatives. In its latest five-year plan, which is the country’s top economic blueprint, EDA was listed as the first cutting-edge technology within the semiconductor industry where China needs to make breakthroughs. This means more government resources will be put into R&D in this area, including China’s government-backed semiconductor investment fund, which invested in the Chinese EDA company Huada Empyrean in 2018.

Huada Empyrean, whose founder has worked in EDA design since the 1980s, is the country’s current leader in domestic EDA software, but it only accounts for 6% of the domestic EDA market. It is also far from developing a whole design flow, meaning its product can only replace a small part of what American companies offer.

There are more startups emerging to fill the gap, most of them led by former Chinese employees of Cadence or Synopsys, like Nanjing-based startup X-Epic and Shanghai-based Hejian Industrial Software. With more international experience and less historical burden, these startups may be better positioned to challenge the status quo, says Douglas Fuller, an associate professor at Copenhagen Business School. “In the longer term, if they cobbled them together, they could be a better alternative to Huada,” he says.

Is it hard for China to develop a domestic EDA alternative?

China has a vibrant software industry, which has produced some world-famous consumer tech apps like Tencent’s WeChat and Alibaba’s Alipay. “But in terms of industrial-use, corporate-use software? That’s China’s drawback,” says Lu. “For the longest time, Chinese industrial policy makers didn’t realize [EDA software] is the real bottleneck.”

It’s an area where it takes decades and billions of dollars of investment to make significant research advancements, so even though Chinese companies want to catch up now, it will take a long time before they make much progress.

One big issue is talent. EDA tool development is such a niche field, and Chinese companies have traditionally struggled to attract many of the small numbers of engineers trained in making EDA tools.

How will it affect the American chip companies?

The latest EDA export control is targeted at a very specialized and advanced section of the industry. “This high-end software is not yet widely used by Chinese firms, so the restriction’s immediate commercial impact on US suppliers is limited,” says Lu.

But export controls are generally not welcomed by chip companies, as such policies can reduce the demand for American products and therefore their income. This is true not just for EDA companies, but also the foundries, IP companies, equipment manufacturers, and everyone else on the supply chain. “You would have a lot of angry companies,” Fuller says. “Not only in the US—not just the EDA companies.”