Subtotal: 1.463,62€ (incl. VAT)

How China takes extreme measures to keep teens off TikTok

China Report is MIT Technology Review’s newsletter about technology developments in China. Sign up to receive it in your inbox every Tuesday.

As I often say, the American people and the Chinese people have much more in common than either side likes to admit. For example, take the shared concern about how much time children and teenagers are spending on TikTok (or its Chinese domestic version, Douyin).

On March 1, TikTok announced that it’s setting a 60-minute default time limit per day for users under 18. Those under 13 would need a code entered by their parents to have an additional 30 minutes, while those between 13 and 18 can make that decision for themselves.

While the effectiveness of this measure remains to be seen (it’s certainly possible, for example, to lie about your age when registering for the app), TikTok is clearly responding to popular requests from parents and policymakers who are concerned that kids are overly addicted to it and other social media platforms. In 2022, teens spent on average 103 minutes per day on TikTok, beating Snapchat (72 minutes) and YouTube (67). The app has also been found to promote content about eating disorders and self-harm to young users.

Lawmakers are taking notice: several US senators have pushed for bills that would restrict underage users’ access to apps like TikTok.

But ByteDance, the parent company of TikTok, is no stranger to those requests. In fact, it has been dealing with similar government pressures in China since at least 2018.

That year, Douyin introduced in-app parental controls, banned underage users from appearing in livestreams, and released a “teenager mode” that only shows whitelisted content, much like YouTube Kids. In 2019, Douyin limited users in teenager mode to 40 minutes per day, accessible only between the hours of 6 a.m. and 10 p.m. Then, in 2021, it made the use of teenager mode mandatory for users under 14. So a lot of the measures that ByteDance is now starting to introduce outside China with TikTok have already been tested aggressively with Douyin.

Why has it taken so long for TikTok to impose screen-time limits? Some right-wing politicians and commentators are alleging actual malice from ByteDance and the Chinese government (“It’s almost like they recognize that technology is influencing kids’ development, and they make their domestic version a spinach version of TikTok, while they ship the opium version to the rest of the world,” Tristan Harris, cofounder of the Center for Humane Technology and a former Google employee, told 60 Minutes.) But I don’t think that the difference between the two platforms is the result of some sort of conspiracy. Douyin would probably look very similar to TikTok were it not for how quickly and forcefully the Chinese government regulates digital platforms.

The Chinese political system allows the government to react swiftly to the consequences of new tech platforms. Sometimes it’s in response to a widespread concern, such as teen addiction to social media. Other times it’s more about the government’s interests, like clamping down on a new product that makes censorship harder. But the shared result is that the state is able to ask platforms to make changes quickly without much pushback.

You can see that clearly in the Chinese government’s approach to another tech product commonly accused of causing teen addiction: video games. After denouncing the games for many years, the government implemented strict restrictions in 2021: people under 18 in China are allowed to play video games only between 8 and 9 p.m. on weekends and holidays; they are supposed to be blocked from using them outside those hours. Gaming companies are punished for violations, and many have had to build or license costly identity verification systems to enforce the rule.

When the crackdown on video games happened in 2021, the social media industry was definitely spooked, because many Chinese people were already comparing short-video apps like Douyin to video games in terms of addictiveness. It seemed as though the sword of Damocles could drop at any time.

That possibility seems even more certain now. On February 27, the National Radio and Television Administration, China’s top authority on media production and consumption, said it had convened a meeting to work on “enforcing the regulation of short videos and preventing underage users from becoming addicted.” News of the meeting sent a clear signal to Chinese social media platforms that the government is not pleased with the current measures and needs them to come up with new ones.

What could those new measures look like? It could mean even stricter rules around screen time and content. But the announcement also mentioned some other interesting directions, like requiring creators to obtain a license to provide content for teenagers and developing ways for the government to regulate the algorithms themselves. As the situation develops, we should expect to see more innovative measures taken in China to impose limits on Douyin and similar platforms.

As for the US, even getting to the level of China’s existing regulations around social media would require some big changes.

To ensure that no teens in China are using their parents’ accounts to watch or post to Douyin, every account is linked to the user’s real identity, and the company says facial recognition tech is used to monitor the creation of livestream content. Sure, those measures help prevent teens from finding workarounds, but they also have privacy implications for all users, and I don’t believe everyone will decide to sacrifice those rights just to make sure they can control what children get to see.

We can see how the control vs. privacy trade-off has previously played out in China. Before 2019, the gaming industry had a theoretical daily play-time limit for underage gamers, but it couldn’t be enforced in real time. Now there is a central database created for gamers, tied to facial recognition systems developed by big gaming publishers like Tencent and NetEase, that can verify everyone’s identity in seconds.

On the content side of things, Douyin’s teenager mode bans a slew of content types from being shown, including videos of pranks, “superstitions,” or “entertainment venues”—places like dance or karaoke clubs that teenagers are not supposed to enter. While the content is likely selected by ByteDance employees, social media companies in China are regularly punished by the government for failing to conduct thorough censorship, and that means decisions about what is suitable for teens to watch are ultimately made by the state. Even the normal version of Douyin regularly takes down pro-LGBTQ content on the basis that they present “unhealthy and non-mainstream views on marriage and love.”

There is a dangerously thin line between content moderation and cultural censorship. As people lobby for more protection for their children, we’ll have to answer some hard questions about what those social media limits should look like—and what we’re willing to trade for them.

Do you think a mandatory daily TikTok time limit for teenagers is necessary? Let me know what you think at zeyi@technologyreview.com.

Catch up with China

1. Over the weekend, the Chinese government held its “two sessions”—an annual political gathering that often signals government plans for the next year. Li Keqiang, China’s outgoing premier, set the annual GDP growth target as 5%, the lowest in nearly 30 years. (New York Times $)

- Because the government is often cryptic about its policy priorities, it becomes an annual tradition to analyze what words are mentioned the most in the premier’s report. This year, “stability,” “food,” and “energy” took center stage. (Nikkei Asia $)

- Some political representatives come from the tech industry, and it’s common (and permissible) for them to make policy recommendations that are favorable to their own business interests. I called it “the Chinese style of lobbying” in a report last year. (Protocol)

2. Wuxi, a second-tier city in eastern China, announced that it has deliberately destroyed a billion pieces of personal data, as part of its process of decommissioning pandemic surveillance systems. (CNN)

3. Diversifying from manufacturing in China, Foxconn plans to increase production in India from 6 million iPhones a year to 20 million, and to triple the number of workers to 100,000 by 2024. (Wall Street Journal $)

4. Chinese diplomats are being idolized like pop-culture celebrities by young fans on social media. (What’s on Weibo $)

5. China is planning on creating a new government agency that has concentrated authority on various data-related issues, anonymous sources said. (Wall Street Journal $)

6. Activists and investors are criticizing Volkswagen after its CEO toured the company’s factories in Xinjiang and said he didn’t see any sign of forced labor. (Reuters $)

7. Wuling, the Chinese tiny-EV brand that outsold Tesla in 2021, has found its first overseas market in Indonesia, and its cars have become the most popular choice of EV there. (Rest of World)

8. The US government added 37 more Chinese companies, some in genetics research and cloud computing, to its trade blacklist. (Reuters $)

Lost in translation

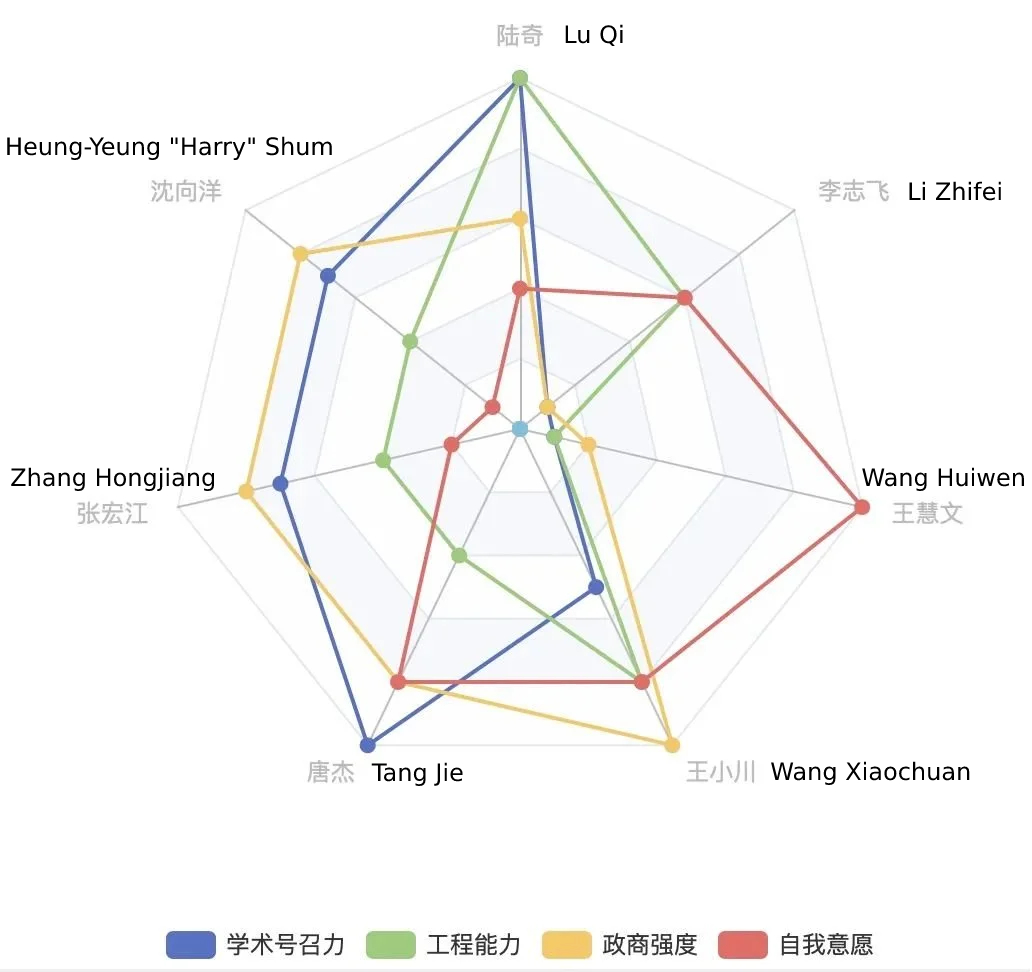

As startups swarm to develop the Chinese version of ChatGPT, Chinese publication Leiphone made an infographic comparing celebrity founders in China to determine who’s most likely to win the race. The analysis takes into consideration four dimensions: academic reputation and influence, experience working with corporate engineers, resourcefulness within the Chinese political and business ecosystem, and proclaimed interest in joining the AI chatbot arms race.

The two winners of the analysis are Wang Xiaochuan, the CEO of Chinese search engine Sogou, and Lu Qi, a former executive at Microsoft and Baidu. Wang has embedded himself deeply in the circles of Tsinghua University (China’s top engineering school) and Tencent, making it possible for him to assemble a star team quickly. Meanwhile, Lu’s experience working on Microsoft’s Bing and Baidu’s self-driving unit makes him extremely relevant. Plus, Lu is now the head of Y Combinator China and has personal connections to Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI and the former president of Y Combinator.

One more thing

Recently, a video went viral in China that shows a driver kneeling in front of his electric vehicle to scan his face. An app in the car system required the driver to verify his identity through facial recognition, and since there’s no camera within the car, the exterior camera on the front of the car was the only option.