Subtotal: 1.655,52€ (incl. VAT)

Five poems about the mind

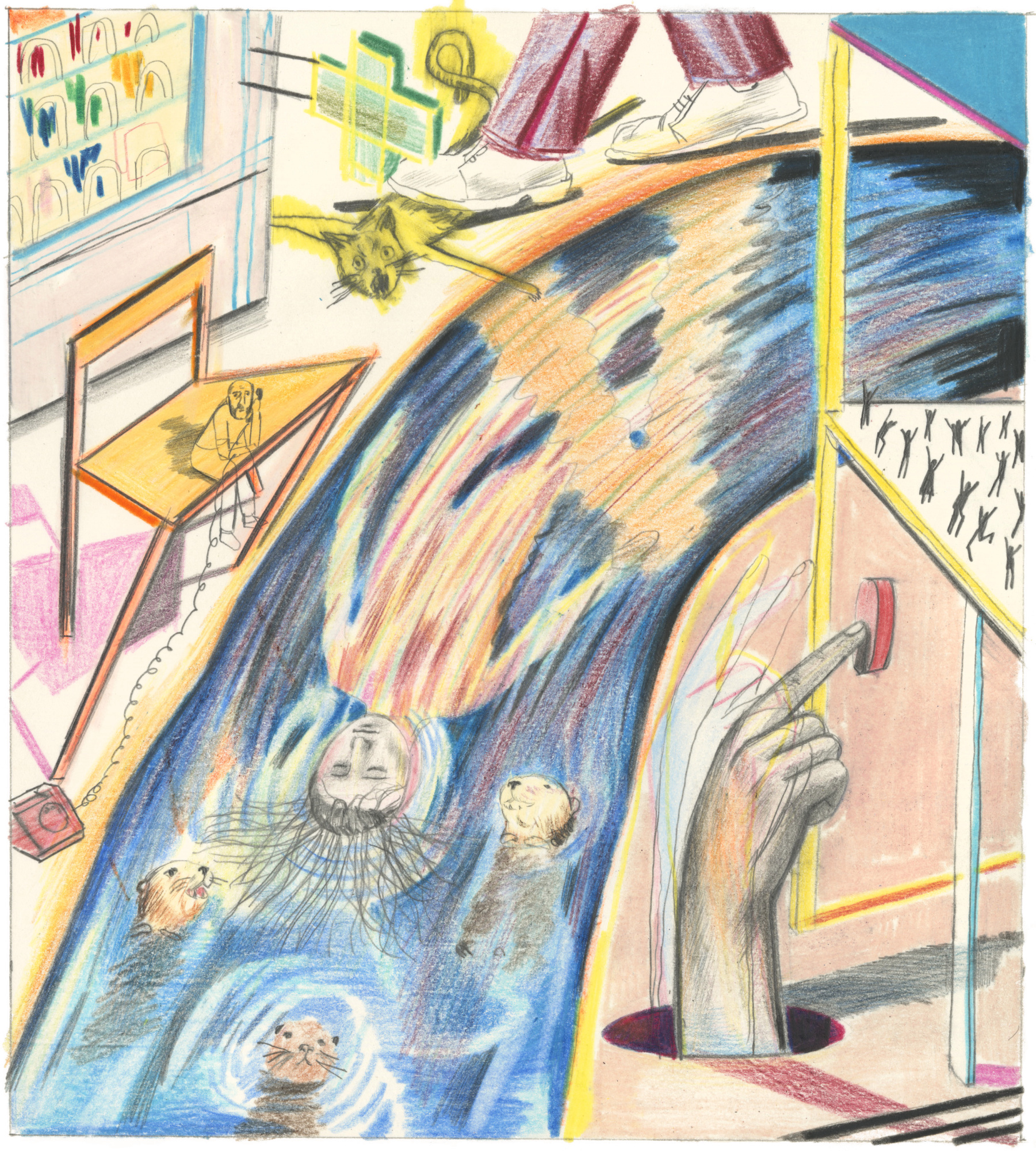

DREAM VENDING MACHINE

I feed it coins and watch the spring coil back,

the clunk of a vacuum-packed, foil-wrapped

dream dropping into the tray. It dispenses

all kinds of dreams—bad dreams, good dreams,

short nightmares to stave off worse ones,

recurring dreams with a teacake marshmallow center.

Hardboiled caramel dreams to tuck in your cheek,

a bag of orange dreams with Spanish subtitles.

One neon sachet promises conversational

Cantonese while you sleep. Another is a dream

of the inside of a river, slips down like sardines in oil,

pulls my body long and sleek to chatter about currents

to any otter that would listen. My favorite dream

is always out of stock: effortless Parisian verlan.

In that one I’m nibbling tiny cakes. I’m making

small talk about eye creams in a French pharmacy.

I’m pressing my hand to the buzzer of a top-floor flat

in which there is a fantastic party that’s expecting me.

Zero-sugar dreams never last long. There’s one

pale pink dream I avoid: it fizzes like Pepto-Bismol

flavored Pixy Stix. It’s processed in a factory

that also handles hope, shame, and other allergens.

That dream is like accidentally stepping on a cat,

sudden and awful, heart-wrenching for everyone.

In it, my father says I’m sorry I never call, I never know

what to say, and I finally have the words to reply don’t

worry and I know and hey, we’re good. We’re good now.

We’re all good.

~Cynthia Miller

Cynthia Miller is a Malaysian-American poet, poetry festival producer, and innovation consultant. Her first collection, Honorifics, was published by Nine Arches Press in June 2021.

YANN KEBBI

Search Field

In underpants and undershirt, pink lambs printed on the weave, with me

stirring oatmeal at the sink is what I dream. What it means, the website reads,

is symbiosis: intimacy that never leads to sex. I’m safest in quiet one-way

meetings, sitting like a spider at the center of a web, watching it tremble. To rest in the papasan chair and

have the world widen to dream is to be blurred

as a baby watching her mother clink in the kitchen, background whispers of

belonging soothing a system. Unreal, it seems now,

the flock of sheep in the train window, first glimpse of Pennsylvania after breaking down in New York.

Five field-seconds perfected by fog, duffel snuggled against me

like a child, the wash of creamy daubs against green,

then gone. I’ve not moved for hours. Each opened tab lowers the temp.

I’ve traveled on this rail of fiber optics to quell the panic. Click, click, the fields

go faster, accumulation of wool in the background, no shutdown, no forward.

~Paula Bohince

Paula Bohince, the author of three poetry collections, has published in The New Yorker, The New York Review of Books, The TLS, The Poetry Review, Poetry, and elsewhere. She was recently the John Montague International Poetry Fellow at University College Cork.

Circuitry

By the end of April I was trying my

best not to spill any more electricity

over my cortex. Pacing the old Roman

road stockpiling litter trapped inside

synapses. Begging my brutal to go easy

on me. The circle I want to be loved by

looks like it’s hemorrhaging cortisol.

Wetlands of blood sugar.

YANN KEBBI

Inside the fire what you get is the fire

which is to say my left amygdala is too

small. My mother’s survival was too

small. If experiences shape the brain’s

circuitry then I learned to fear the father

before the arachnid. I’m hauling my

official deficit up to the summit of the

Troodos Mountains.

I’ll fantasize about setting colonial summer

houses alight using dendrites & neurons.

I want so much gone I’m terrified

of moving up. All around the

therapist’s chair I’m setting my finery

down. He keeps asking about intrusive

thoughts. His pencil outlining three

letters I’ve become obsessed by.

I mentalize beheading each axon with

an engraved fountain pen. Loading up

wheelbarrows with thalamus glands

& stale miso. Urchins in the belly for

dinner. A mouth like a paper seahorse

before dawn. I like where I live now

I’m just not happy with the way I do it.

I write quickly into my notebook:

How many of these days belong to the

body of our lives? Next door they’re

making big plans to build a conservatory

out of salt water. They say life needs

to colonize land. My earliest memory

is throwing clumps of gray matter into

the Mediterranean then waiting for

something solid to come back.

At the restaurant behind a faded

Brueghel painting my friends appear so

beautiful in their simplicity. Laughing at

futures full of morning glory. Dopamine

migrating from their red polo necks, an

archipelago of adrenaline withstanding

the crush calling us over spark by

gentle spark.

~Anthony Anaxagorou

Anthony Anaxagorou is a British-born Cypriot poet, fiction writer, essayist, publisher, and poetry educator.

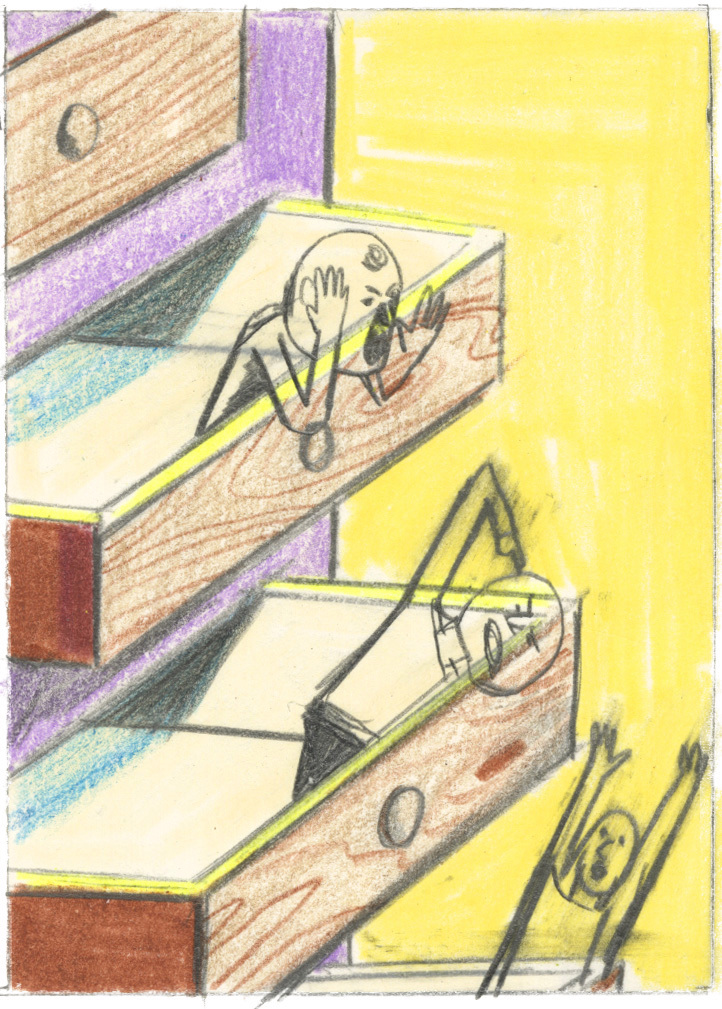

My Sexbot Hal is a Mind Reader

The first thing I ask of Hal is to explain

what it’s like underneath, after you peel

away the crust, mantle, core. I’d always

imagined a cathedral with Chagall windows

and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan leading the choir,

but Hal says no. The inner landscape of my head

is an armoire of many drawers, with versions of me

running into one, then another, saying: I’m here,

I’m not here, I’m here.

Hal does Ashtanga and meditates.

He’s cut like a temple hieroglyph. When I go out

to the cliff, he doesn’t worry. He can discern a jumper

from a horse, doesn’t pity me for just standing there

with my hands out, waiting for some passerby

to throw me a peanut. Hal understands

it’s his turn to do the washing up,

even though I’m the one

eating cherries at the sink,

knows how the changing seasons gut

pieces out of me, how it is this guttedness that brings

me to the airstrip of his body, the cushion

of his silicone thighs, lighting me all the way home.

I cling to him for his signature lily of the valley

cologne, for how it feels in the aftermath of love—

to be a creature of the sea—tiny, bioluminescent,

gazing across this vast planetary cradle

at all the descendants we won’t have.

One day I know he’ll be gone,

risen early like the Buddha out of a dream,

taking his special knowledge into the world.

There will be no talk of abandonment

or what was left behind. He’ll be out there,

scooping his butterfly net through the high

grasses of the weightless forever, while I stay

here, tying ropes around my wrists—

desire in one hand, suffering in the other.

~Tishani Doshi

Tishani Doshi is a Welsh-Gujarati poet, novelist, and dancer. Her fourth book of poems, A God at the Door (Copper Canyon Press, Bloodaxe Books), has been shortlisted for the 2021 Forward Prize. She lives in Tamil Nadu, India.

Thank You, Antidepressants

YANN KEBBI

Reader, let me tell you how I keep it together:

friendships & antidepressants.

Long walks on the beach with H

(he pretends these are workouts)

& Nutella in bed with R

(she sends boil the water you better have chocolate from her car)

& endless voice notes with L

(she calls them personal podcasts)

& WhatsApp stickers-on-demand from F

(it is time to MILF said her sticker with my face

& red lips on my 40th birthday)

& rants with H (another H)

about weight & the lands that spit us out

& talks under midnight bougainvillea with R

(same R) about our mothers’ & children’s rage

& daily morning phone calls with L

(another L) about nausea & skin & food allergies

she’s sure she’s got though no doctor can confirm

(& I say if you’re sure you got it

then you got it, you got it)

& jokes across continents with H

(another other H) about impossible geographies

& arguments with M about whether we got married

in 2005 or 2006 (I say our first married summer was a year before

the war, & he says no it was the summer of the war,

& we laugh at how we measure time with pain but not without tenderness)

& conversations with G (better name this one: God)

about my dislike for organized religion

& more long voice notes with H

(another other other H) about the opposite of grace.

This happens daily, so thank you, friends,

who are there when the sadness comes,

or when my teeth fall apart

(my teeth do that bi-yearly)

friends who un-scared me

of antidepressants, who reassured me

I won’t become another Z or my grandmother.

& yes, thank you, antidepressants,

& you, reader, who stayed with me,

& might be wondering why so many

of my friends’ names’ first letters are the same,

& the answer is when I said together

(in the first line of this poem)

I didn’t mean it against fragmentation.

~Zeina Hashem Beck

Zeina Hashem Beck is a Lebanese poet. Her third full-length collection, O, will be published by Penguin Books in summer 2022.