Exposing the messy, technologized, and undervalued nature of reproductive labor

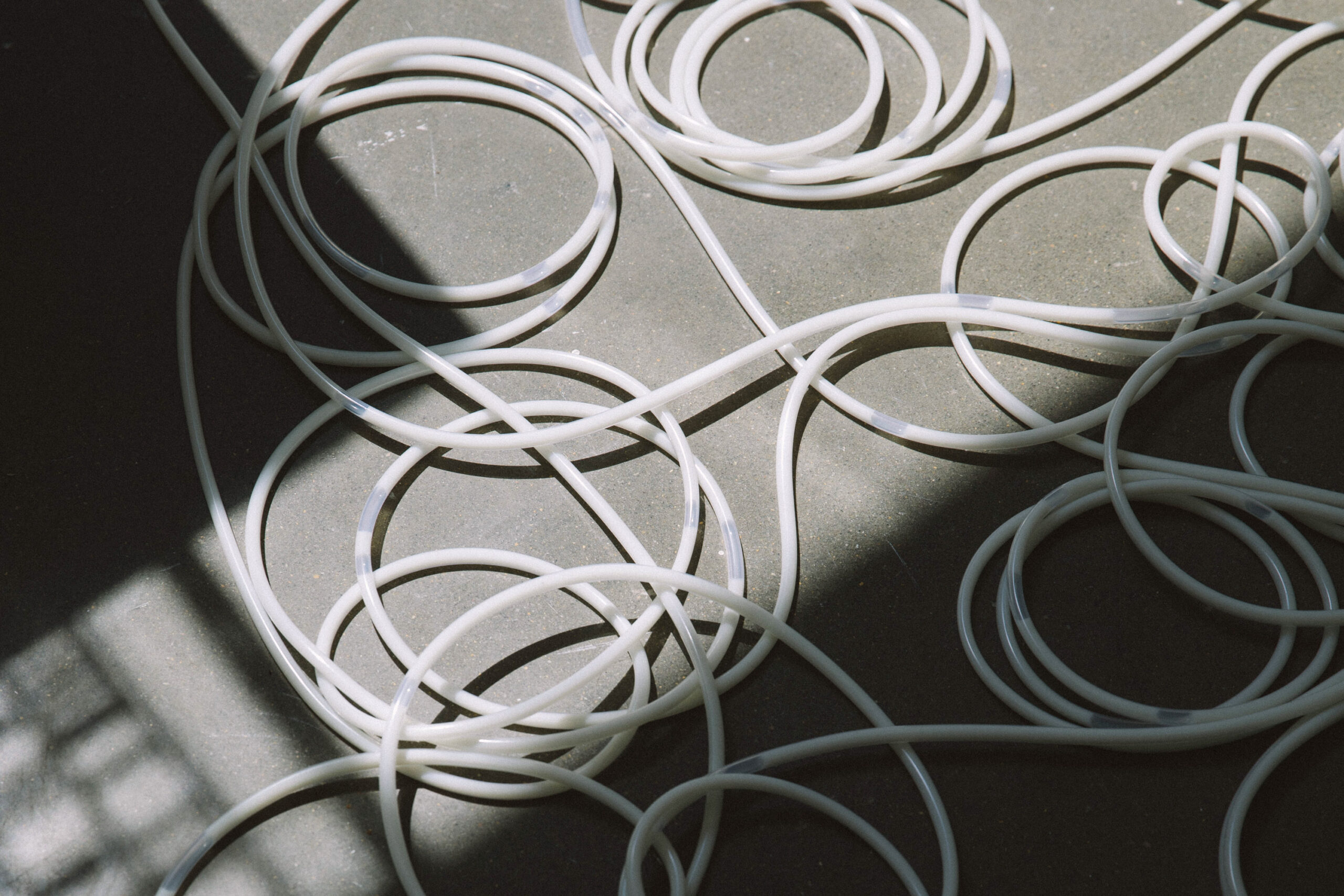

Messy coils of plastic tubing sprawl across the gallery’s concrete floor. The liquid inside—opaque, white with a yellowish tinge—pulses once, twice, and the eye tracks its progress thanks to the air bubbles cycling through the loops. Could that be … milk? Follow the tubing back to an unassuming rectangular box. If it is milk, a panicked brain might ask, where is the mother?

At this moment the mother, artist Ani Liu, is standing by the door of the pocket-size Cuchifritos Gallery + Project Space in Lower Manhattan, wrapped in a tie-dyed T-shirt dress for tonight’s opening of her solo exhibition, “Ecologies of Care.” But she has also sat, pumping milk, in the broom closet next to her classroom at the University of Pennsylvania; in her basement studio in Queens; on trains and in cars. The volume of milk circulating through Untitled (pumping) and Untitled (feeding through space and time) represents a month of such sessions, or 5.85 gallons—some of the invisible labor of motherhood. It also represents modern breastfeeding technology—specifically, the Spectra pump that allowed Liu the alleged freedom to return to the workplace just weeks after having her first child. After headlines about a national formula shortage earlier this year, the liquid seems even more precious.

The milk in this exhibit is not real. After much experimenting, Liu ended up filling the pump with “magician’s milk,” a proprietary formula, purchased from a magic shop, that requires no refrigeration and comes with the warning “Not a food product. Do not drink!” Nevertheless, it looks convincing. When installing the piece, Liu originally considered having the milky coils take over the whole gallery floor, even more aggressively immersing visitors in the visual and aural landscape of newborn care.

Liu, who holds graduate degrees from the Harvard Graduate School of Design and the MIT Media Lab, resumed teaching just five days after she gave birth in 2021. She had just signed a new contract as an associate professor of practice at Penn, and the university offers maternity leave only to employees of more than a year. Though she was initially allowed to teach over Zoom from her home in Queens, she ended up pumping more than nursing. “I developed this really intense relationship with my pump, where just hearing the sound of it made me let down, rather than my baby’s cry. It was just such a weird Donna Haraway cyborg moment,” she says, referring to the feminist science and technology scholar who wrote, of the cyborg, that it “does not dream of community on the model of the organic family.”

It was also a moment that led Liu to new research. Her discoveries emerge in the works on display in the Cuchifritos Gallery, which include a series of three-dimensional meditations on technology, motherhood, and childhood in our algorithm-enabled world.

Pumping is also on displayas part of the second edition of the exhibition “Designing Motherhood,” now at the MassArt Art Museum in Boston. Michelle Millar Fisher, part of the curatorial team, wrote that the work “cuts right to the heart of the ways in which reproductive labor is hidden, romanticized, socially taboo, and undervalued.”

Liu’s work has additional urgency and resonance after the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Who controls, who supports, and who performs reproductive labor are not just bedroom or broom closet questions (and never should have been); they are playing out on the streets, in state houses, and in the Supreme Court.

Millar Fisher has drawn parallels between Liu’s pumping installation and the work of the artist Hiromi Marissa Ozaki, known as Sputniko!, whose 2010 Menstruation Machine simulates the experience of menstruation; the video part of the piece shows a fictional day in the life of a young man who builds a device to experience life as a person with a uterus.

Liu has long been fascinated by this sort of simulated experience. In 2019, after watching YouTube videos of men sampling simulated labor pains in order to understand their wives’ experience, and finding them wanting on multiple levels, she decided to create her own apparatuses, including a garment called Untitled (woman pains), fitted with a belly and electrodes, that would allow any non-pregnant person to experience the weight and discomforts of pregnancy. Another in the series, Untitled (small inconveniences), simulates incontinence. Made in collaboration with fabricator Randi Shandroski, the garments look like lingerie and simulate one result of sex, but these are not experiences generally considered sexy.

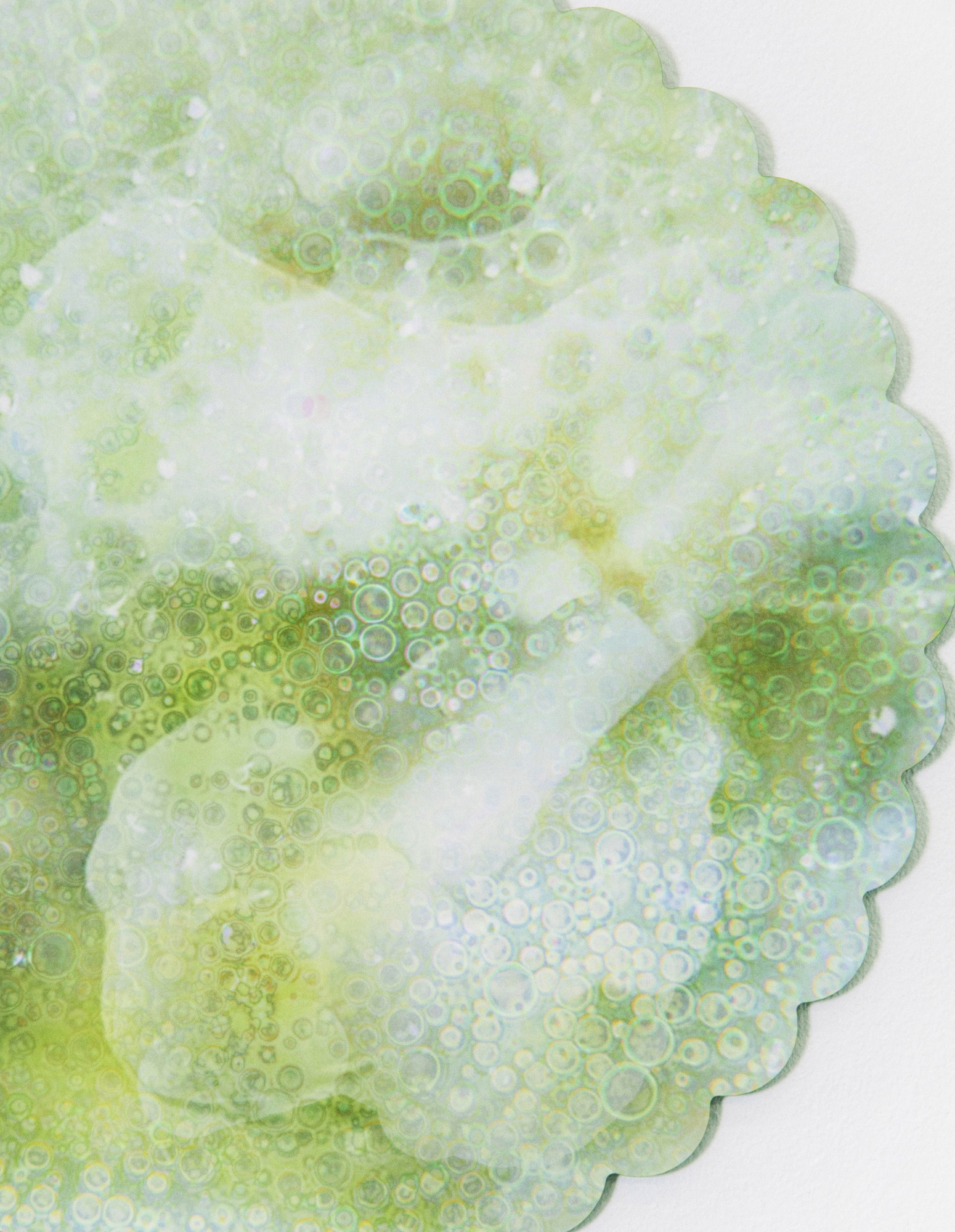

Her pieces demonstrate a mischievous humor, embedded in the everyday indignities of modern life. Consumer culture might seem to celebrate pregnancy, but the products pushed to pregnant people focus on all the things that are “wrong” with the pregnant body: mood swings, stretch marks, incontinence. In response, Liu created Consumerist Pregnancy, which includes a series of creams, masks, and medications, designed in high millennial style (monochrome packaging, sans serif fonts) but honestly labeled “Fatigue,” “Shortness of Breath,” “Swelling.” If you saw them on a pharmacy shelf you would be initially attracted, but once you read the description, even as a person who has been pregnant, it would be hard not to say No, thank you.

The Surrogacy features a 3D-printed model of a multichambered pig’s uterus which, upon approach, reveals human fetuses in each chamber, a commentary on the ethics of assisted reproduction and the exploitation of human surrogates. Hung on the wall of the gallery is a spreadsheet that, upon inspection, reveals itself to be a minute-by-minute accounting of all the touchpoints of the first month of Liu’s daughter’s life (she’s now two): every feeding, every pee, every poop. One inspiration for the spreadsheet was Post-Partum Document, a 1973–’79 work by conceptual artist Mary Kelly, in which Kelly displayed the liners from her son’s cloth diapers as monochromes in white frames.

Untitled (Consumerist Pregnancy Reports): A set of ritual devices and consumable products made to simulate the biological experience of pregnancy.

Liu’s work stands out not just for its topicality, or the precision with which it zeroes in on the frustrations of 21st-century motherhood, but for its range. She is the kind of artist of whom you might say that she “works at the intersection of art and technology.” But that should really be “technologies,” plural. Different pieces have required her to delve into the intricacies of pumps, circuitry, machine learning, microscopy, and 3D printing, developing enough understanding of each field to identify the necessary expertise of her collaborators. When she was at the Media Lab she joined a biohacking club, which she found to be the ideal educational experience. No matter the question, she says, “someone would sit down with a beer and explain it.”

Even her thesis project at the Media Lab, Mind Controlled Spermatozoa (2016–2017), recently wiggled back into the news as six Supreme Court justices, five male and one female, declared jurisdiction over child-bearing bodies.

For that project Liu researched galvanotaxis, the directed movement of an organism or cell in response to an electric field or current. In the accompanying video, she dons an EEG machine, which measures electrical activity in the brain. She then applies those signals to a magnified sample of her now-husband’s sperm and is actually able to direct the movement of spermatozoa to the left and right with her thoughts. (The science is real, if dramatized for the video.) As she writes, “I seek to challenge this status quo by engineering a system by which I (a woman) can control something inherently and symbolical male: spermatozoa (sperm).” The subtitle of the piece is “Women of STEAM Grab Back.”

A week after the leak of the draft Supreme Court decision overturning Roe v. Wade, Liu put the piece up on her Instagram with a new caption. “In the few times I’ve shown this work, men have often expressed to me how violating and unnatural it is to control sperm—sperm that is not even theirs, or in their body,” she wrote. “[T]hink of the plight of female bodies, that are constantly under threat of being controlled, regulated, censored.” Liu’s work attempts to shed light on the constant policing of cisgender women’s bodies, using the very machines and marketing techniques that typically oppress.

Design critic Alexandra Lange is the author of Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall.