China’s path to modernization has, for centuries, gone through my hometown

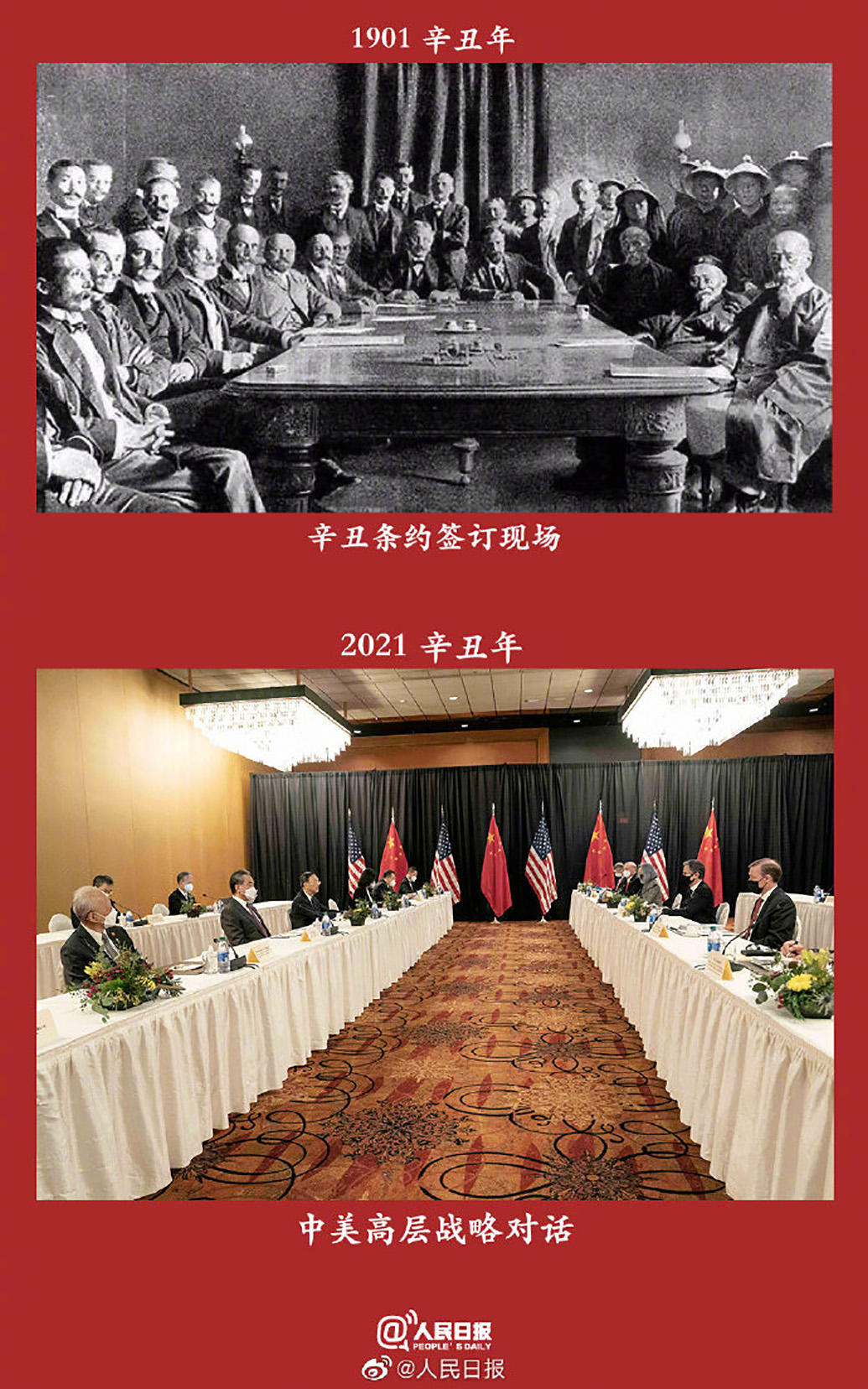

One day in late March, People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s official newspaper, shared a pair of photos on Chinese social media.

The first, in black and white, was of the signing of the Boxer Protocol, a 1901 treaty between the Qing empire, which ruled China at the time, and 11 foreign nations. Troops from eight of these countries, including the US, had occupied Beijing following sieges on their embassies by a peasant militia known as the Boxers. Among a litany of concessions, the Qing government agreed to pay the eight occupying powers an indemnity of 450 million taels of silver (about $10 billion in today’s dollars), almost twice its annual revenue. The Boxer Protocol is etched into the Chinese consciousness as a searing reminder of the country at its weakest.

The second image, in vivid color, was from the previous day, at an acrimonious summit held in Alaska between top Chinese and American officials. It was the first high-level meeting between the two governments during the Biden administration. The officials criticized one another’s governments for human rights abuses and belligerence on the international stage. At the end of the opening session, Yang Jiechi, director of foreign affairs for the Chinese Communist Party, scolded his American counterparts: “Haven’t we, the Chinese people, suffered from foreign bullies long enough? Haven’t we been penned in by foreign nations and stopped from progress long enough?”

The People’s Daily post quoted Yang as saying further: “You, the United States, are not qualified to claim that you are speaking to China from a position of strength.” This struck a nerve; the post has been liked almost 2 million times, and Yang’s quote has found its way to T-shirts, stickers, and cell-phone covers sold in China. To many in the country, the harsh words carry the sweet taste of revenge. China is finally strong enough to stand up to the most powerful nation on earth and demand to be treated as its equal.

signing of the Boxer

Protocol with one from the Alaska summit.

The post has been

liked almost 2 million

times.

From the last Chinese empire to the current People’s Republic, generations of politicians and intellectuals have sought ways to build a strong China. Some imported tools and ideas from the West. Others left China for a better education, but the homeland still beckoned. They pondered the relationships between East and West, tradition and modernity, national allegiance and cosmopolitan ideals. Their accomplishments and regrets have shaped the path of China’s development and mapped the contours of Chinese identity.

I’m a product of their complex legacy. I grew up in Hefei, a medium-sized city in central-eastern China. The Hefei of my childhood was a humble place, known for ancient battlegrounds, sesame snacks, and a few good universities. I spent the first 19 years of my life there and left in 2009 to pursue my PhD in physics in the US, where I now live and work. Watching my birth country’s ascent conjures up mixed feelings. I’m glad that the majority of Chinese people enjoy a higher standard of living. I’m also alarmed by the hardened edge to China’s new superpower status. Economic growth and technological advancements have not ushered in more political freedoms or a more tolerant society. The Chinese government has become more authoritarian and its people more nationalistic. The world feels more fractured today.

The Chinese government has become more authoritarian and its people more nationalistic. The world feels more fractured today.

Hefei is now a budding metropolis with new research centers, manufacturing plants, and technology startups. For two of the city’s proudest sons, born a century apart, a strong homeland armed with science and technology was the aspiration of a lifetime. One of these men was the late Qing’s most revered statesman. The other is one of the first two Nobel laureates from China. The Boxer Protocol marked the end of one career and laid the foundation for the other. I grew up with their names and have been returning to their stories. They teach me about the forces that propelled China’s rise, the way lives can be squeezed by the pressures of geopolitics, and the risks of using science for state power.

In 1823, Li Hongzhang was born to a wealthy household in Hefei, then a small provincial capital surrounded by farmland. Like his father and brother before him, Li excelled in the imperial exams, China’s centuries-old system for selecting officials. Over six feet tall and with a piercing gaze, he commanded space and attention. He distinguished himself in suppressing peasant rebellions and rose quickly in the imperial court to become the Qing empire’s highest-ranking governor, its commerce minister, and its de facto foreign minister.

After China lost to British and French forces in the Opium Wars, Li and his allies launched a wide range of reforms. They called it the Movement for Western Affairs, also known as “self-strengthening.” The strategy was best summed by the scholar Wei Yuan in an 1844 book, Illustrated Treatise on the Maritime Kingdoms: “Learn advanced technologies from the barbarians to keep barbarian invaders at bay.”

To the Chinese literati, the world was divided between hua, the homeland of civilized glory, and yi, the places where barbarians dwelled. British gunboats on the southern shore had shaken but not shattered this centuries-old belief. Proponents of self-strengthening claimed that Chinese tradition was the base onto which Western technology could be grafted for practical use. As the historian Philip Kuhn has argued, such logic also implied that technology was culturally neutral and could be detached from political systems.

A classically trained scholar and battle-tested general, Li championed both civilian and military enterprises. He petitioned the emperor to construct the first Chinese railroad and founded the country’s first privately owned steamship company. He allocated generous government funding for the Beiyang Fleet, China’s first modern navy. In 1865, Li oversaw the establishment of the Jiangnan Arsenal, the largest weapons factory in East Asia at the time. In addition to producing advanced machinery for war, the arsenal also included a school and a translation bureau, which translated scores of Western textbooks on science, engineering, and mathematics, establishing the vocabulary in which these subjects would be discussed in China.

Li also supervised China’s first overseas education program, which sent a cohort of Chinese boys aged 10 to 16 to San Francisco in the summer of 1872. After a promising start, the mission was derailed by anti-Chinese racism in the US and conservative obstruction at home. Some students, upon returning to China, were held and questioned by the authorities about their loyalty. After nine bumpy years, the program was shut down in 1881 on the eve of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Meanwhile, neighboring Japan had adopted not only the West’s technology but also its governing methods, transforming a feudal society into a modern industrial state with a formidable military. For centuries, the Chinese elite had looked down upon Japan, dismissing it as small and inferior. When the two countries went to war in 1894, ostensibly over the status of Korea, the real prize was status as the preeminent Asian power. Japan won decisively. It was six years after this devastating loss that Li signed the Boxer Protocol on behalf of the Qing government. He died two months later.

Li Hongzhang could not have imagined that after his death, the most shameful chapter of his career would, at the whimsical hand of geopolitics, contribute to his lifelong dream of bringing Western science and education to China.

By the start of the 20th century, the last Chinese empire had lost its legitimacy. Armed rebellions were erupting across the country. The Qing regime was overthrown in 1911, and the Republic of China was born. Progressive intellectuals saw Chinese tradition as “rotten and decayed,” a cultural albatross holding their country back. They believed that national salvation demanded embracing Western ideas. The few dissenting voices were sidelined.

China’s path to westernization received some early assistance from the US. Hoping to improve relations between the two countries, the US government decided to return almost half the American portion of the indemnity China had agreed to pay in the Boxer Protocol. With the US side dictating the terms, part of the remittance went toward a program known as the Boxer Indemnity Scholarships, which provided one of the few pathways for Chinese students to study in the US. The bulk of the returned payment was used to establish a Western-style preparatory school, which became Tsinghua University, China’s premier technological institution. Li Hongzhang could not have imagined that after his death, the most shameful chapter of his career would, at the whimsical hand of geopolitics, contribute to his lifelong dream of bringing Western science and education to China. Tsinghua took its motto from the ancient text of I Ching, the Book of Changes: “The work of self-strengthening is ceaseless. The virtuous carry the world with generosity.”

In 1945, a young man named Chen Ning Yang graduated from Tsinghua and arrived at the University of Chicago for his PhD on a Boxer Indemnity Scholarship. Inspired by the autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, which he had read as a child, the aspiring physicist from Hefei gave himself the English name Frank.

After World War II ended, Nationalists and Communists continued to battle in China. Yang and his small cohort of overseas Chinese students faced a pressing dilemma: Should they stay in the West—despite its racism and anticommunist paranoia—and enjoy social stability, material comfort, and career opportunities? Or should they return to their impoverished homeland after graduation and help it rebuild?

In a long letter to Yang in 1947, his college classmate Huang Kun wrote, “It’s difficult to imagine how intellectuals like us can affect the fate of a nation. Independent minds like us, once we go back, will certainly get crushed like grains in a mill … but I still sincerely believe that whether China has us makes a difference.”

Huang was studying in England at the University of Bristol. He returned to China in 1951, two years after the Communist victory, and pioneered the field of semiconductor physics in the country. Deng Jiaxian, Yang’s best friend since adolescence, boarded a ship back nine days after receiving his PhD from Purdue. He became a leader in China’s fledgling nuclear weapons program. Some overseas Chinese scientists, dreading Communist rule, followed the Nationalist government to Taiwan, Yang’s former mentor Wu Ta-You among them. But Yang opted to stay in the US after getting his doctorate, moving in 1949 to the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. There he would spend the better part of the next two decades. He would not see any of his old friends for many years.

In 1957, Yang and Tsung-Dao Lee, a fellow Chinese graduate of the University of Chicago, won the Nobel Prize for proposing that when some elementary particles decay, they do so in a way that distinguishes left from right. They were the first Chinese laureates. Speaking at the Nobel banquet, Yang noted that the prize had first been awarded in 1901, the same year as the Boxer Protocol. “As I stand here today and tell you about these, I am heavy with an awareness of the fact that I am in more than one sense a product of both the Chinese and Western cultures, in harmony and in conflict,” he said.

Yang became a US citizen in 1964 and moved to Stony Brook University on Long Island in 1966 as the founding director of its Institute for Theoretical Physics, which was later named after him. As the relationship between the US and China began to thaw, Yang visited his homeland in 1971—his first trip in a quarter of a century. A lot had changed. His father’s health was failing. The Cultural Revolution was raging, and both Western science and Chinese tradition had been deemed heresy. Many of Yang’s former colleagues, including Huang and Deng, were persecuted and forced to perform hard labor. The Nobel laureate, on the other hand, was received like a foreign dignitary. He met with officials at the highest levels of the Chinese government and advocated for the importance of basic research.

In the years that followed, Yang visited China regularly. At first, his trips drew attention from the FBI, which saw exchanges with Chinese scientists as suspect. But by the late 1970s, hostilities had waned. Mao Zedong was dead. The Cultural Revolution was over. Beijing adopted reforms and opening-up policies. Chinese students could go abroad for study. Yang helped raise funding for Chinese scholars to come to the US and for international experts to travel to conferences in China, where he also helped establish new research centers. When Deng Jiaxian died in 1986, Yang wrote an emotional eulogy for his friend, who had devoted his life to China’s nuclear defense. It concluded with a song from 1906, one of his father’s favorites: “[T]he sons of China, they hold the sky aloft with a single hand … The crimson never fades from their blood spilled in the sand.”

from left) Val Fitch, James Cronin, Samuel C.C. Ting, and Isidor Isaac Rabi

Yang retired from Stony Brook in 1999 and moved back to China a few years later to teach freshman physics at Tsinghua. In 2015, he renounced his US citizenship and became a citizen of the People’s Republic of China. In an essay remembering his father, Yang recounted his earlier decision to emigrate. He wrote, “I know that until his final days, in a corner of his heart, my father never forgave me for abandoning my homeland.”

In 2007, when he was 85 years old, Yang stopped by our hometown on an autumn day and gave a talk at my university. My roommates and I waited outside the venue hours in advance, earning precious seats in the packed auditorium. He took the stage to thunderous applause and delivered a presentation in English about his Nobel-winning work. I was a little perplexed by his choice of language. One of my roommates muttered, wondering whether Yang was too good to speak in his mother tongue. We listened attentively nevertheless, grateful to be in the same room as the great scientist.

A college junior and physics major, I was preparing to apply to graduate school in the US. I’d been raised with the notion that the best of China would leave China. Two years after hearing Yang in person, I too enrolled at the University of Chicago. I received my PhD in 2015 and stayed in the US for postdoctoral research.

Months before I bid farewell to my homeland, the central government launched its flagship overseas recruitment program, the Thousand Talents Plan, encouraging scientists and tech entrepreneurs to move to China with the promise of generous personal compensation and robust research funding. In the decade since, scores of similar programs have sprung up. Some, like Thousand Talents, are supported by the central government. Others are financed by local municipalities.

Beijing’s aggressive pursuit of foreign-trained talent is an indicator of the country’s new wealth and technological ambition. Though most of these programs are not exclusive to people of Chinese origin, the promotional materials routinely appeal to sentiments of national belonging, calling on the Chinese diaspora to come home. Bold red Chinese characters headlined the web page for the Thousand Talents Plan: “The motherland needs you. The motherland welcomes you. The motherland places her hope in you.”

These days, though, the website isn’t accessible. Since 2020, mentions of the Thousand Talents Plan have largely disappeared from the Chinese internet. Though the program continues, its name is censored on search engines and forbidden in official documents in China. Since the final years of the Obama administration, the Chinese government’s overseas recruitment has come under intensifying scrutiny from US law enforcement. In 2018, the Justice Department started a China Initiative intended to combat economic espionage, with a focus on academic exchange between the two countries. The US government has also placed various restrictions on Chinese students, shortening their visas and denying access to facilities in disciplines deemed “sensitive.”

My mother is afraid that the borders between the US and China will be closed again as they were during the pandemic, shut down by forces just as invisible as a virus and even more deadly.

There are real problems of illicit behavior in Chinese talent programs. Earlier this year, a chemist associated with Thousand Talents was convicted in Tennessee of stealing trade secrets for BPA-free beverage can liners. A hospital researcher in Ohio pled guilty to stealing designs for exosome isolation used in medical diagnosis. Some US-based scientists failed to disclose additional income from China in federal grant proposals or on tax returns. All these are cases of individual greed or negligence. Yet the FBI considers them part of a “China threat” that demands a “whole-of-society” response.

The Biden administration is reportedly considering changes to the China Initiative, which many science associations and civil rights groups have criticized as “racial profiling.” But no official announcements have been made. New cases have opened under Biden; restrictions on Chinese students remain in effect.

Seen from China, the sanctions, prosecutions, and export controls imposed by the US look like continuations of foreign “bullying.” What has changed in the past 120 years is China’s status. It is now not a crumbling empire but a rising superpower. Policymakers in both countries use similar techno-nationalistic language to describe science as a tool of national greatness and scientists as strategic assets in geopolitics. Both governments are pursuing military use of technologies like quantum computing and artificial intelligence.

“We do not seek conflict, but we welcome stiff competition,” National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan said at the Alaska summit. Yang Jiechi responded by arguing that past confrontations between the two countries had only damaged the US, while China pulled through.

Much of the Chinese public relishes the prospect of competing against the US. Take a popular saying of Mao’s: “Those who fall behind will get beaten up!” The expression originated from a speech by Joseph Stalin, who stressed the importance of industrialization for the Soviet Union. For the Chinese public, largely unaware of its origins, it evokes the recent past, when a weak China was plundered by foreigners. When I was little, my mother often repeated the expression at home, distilling a century of national humiliation into a personal motivation for excellence. It was only later, in adulthood, that I began to question the underlying logic: Is a competition between nations meaningful? By what metric, and to what end?

After 11 years of designing particle detectors and searching for dark matter, I left physics at the end of 2020 for a position working on science policy and ethics. It was a very difficult decision, and I’m still reckoning with the sense of loss associated with the change. But with every passing day, news from my birth country and my adopted home reminds me of why I made the choice. Advancements in science and technology have created unprecedented wealth—as well as inequality and capacity to cause harm. In the fevered race for power and supremacy, concerns about ethics and sustainability are drowned out by jingoistic cheers.

My mother has been trying to persuade me to move back to China. She tells me how Hefei has shed its rusty, blue-collar image to become a modern city. “It has a new subway system! Do you know how fast it is?” she says over the phone. The sincerity in her voice breaks my heart.

I want to say that I do not care for fast trains or new buildings—I really don’t—but I also know that my mother does not care for these things either. Her pride in her country’s development is genuine. If there’s anything she loves more than her homeland, though, it’s her child. My mother wants me to come back not because of some lofty ideals of patriotism, though she believes in them; nor for my career advancement, though the Chinese government has been investing heavily in the fundamental sciences. My mother wants me to come back because she is afraid.

My mother is afraid that the borders between the US and China will be closed again as they were during the pandemic, shut down by forces just as invisible as a virus and even more deadly. She fears for my safety in a foreign land that is in many ways increasingly hostile to my race and nationality. What my mother does not know, or refuses to accept, is that the homeland is not safe for me either. A state can command the world’s second-largest economy and a strong military, and still be too fragile to allow dissent. Sometimes, life as a Chinese person means following one’s conscience with no refuge in sight.

At Li Hongzhang’s family temple on the outskirts of Hefei, there is an old yulan tree. Tall and fragrant, yulan was a favorite of royalty. Legend has it that this tree was a gift from the Japanese prime minister on Li’s 70th birthday. Li planted it himself. In less than a year, the two countries would be at war. The tree has outlived both men and the empires they served. It blossoms every year and occasionally bears fruit. It is a witness, and also a teacher. One day, when I’m able to go back to China and to Hefei, I hope to visit Li’s old residence.

I hope to be there in the spring, when the yulan blooms. Its flowers will be the purest white. Its petals will be thick and smooth. Its branches will lift into the sky. When the sun hits at just the right spot, its shadow will carry the shape of home.

Yangyang Cheng is a particle physicist and a postdoctoral fellow at Yale Law School.