Inside the most dangerous asteroid hunt ever

If you were told that the odds of something were 3.1%, it really wouldn’t seem like much. But for the people charged with protecting our planet, it was huge.

On February 18, astronomers determined that a 130- to 300-foot-long asteroid had a 3.1% chance of crashing into Earth in 2032. Never had an asteroid of such dangerous dimensions stood such a high chance of striking the planet. For those following this developing story in the news, the revelation was unnerving. For many scientists and engineers, though, it turned out to be—despite its seriousness—a little bit exciting.

While possible impact locations included patches of empty ocean, the space rock, called 2024 YR4, also had several densely populated cities in its possible crosshairs, including Mumbai, Lagos, and Bogotá. If the asteroid did in fact hit such a metropolis, the best-case scenario was severe damage; the worst case was outright, total ruin. And for the first time, a group of United Nations–backed researchers began to have high-level discussions about the fate of the world: If this asteroid was going to hit the planet, what sort of spaceflight mission might be able to stop it? Would they ram a spacecraft into it to deflect it? Would they use nuclear weapons to try to swat it away or obliterate it completely?

At the same time, planetary defenders all over the world crewed their battle stations to see if we could avoid that fate—and despite the sometimes taxing new demands on their psyches and schedules, they remained some of the coolest customers in the galaxy. “I’ve had to cancel an appointment saying, I cannot come—I have to save the planet,” says Olivier Hainaut, an astronomer at the European Southern Observatory and one of those who tracked down 2024 YR4.

Then, just as quick as history was made, experts declared that the danger had passed. On February 24, asteroid trackers issued the all-clear: Earth would be spared, just as many planetary defense researchers had felt assured it would.

How did they do it? What was it like to track the rising (and rising and rising) danger of this asteroid, and to ultimately determine that it’d miss us?

This is the inside story of how, over a span of just two months, a sprawling network of global astronomers found, followed, mapped, planned for, and finally dismissed 2024 YR4, the most dangerous asteroid ever found—all under the tightest of timelines and, for just a moment, with the highest of stakes.

“It was not an exercise,” says Hainaut. This was the real thing: “We really [had] to get it right.”

IN THE BEGINNING

December 27, 2024

THE ASTEROID TERRESTRIAL-IMPACT LAST ALERT SYSTEM, HAWAII

Long ago, an asteroid in the space-rock highway between Mars and Jupiter felt a disturbance in the force: the gravitational pull of Jupiter itself, king of the planets. After some wobbling back and forth, this asteroid was thrown out of the belt, skipped around the sun, and found itself on an orbit that overlapped with Earth’s own.

“I was the first one to see the detections of it,” Larry Denneau, of the University of Hawai‘i, recalls. “A tiny white pixel on a black background.”

Denneau is one of the principal investigators at the NASA-funded Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescopic network. It may have been just two days after Christmas, but as usual, he followed procedure as if it were any other day of the year and sent the observations of the tiny pixel onward to another NASA-funded facility, the Minor Planet Center (MPC) in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

There’s an alternate reality in which none of this happened. Fortunately, in our timeline, various space agencies—chiefly NASA, but also the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency—invest millions of dollars every year in asteroid-spotting efforts.

And while multiple nations host observatories capable of performing this work, the US clearly leads the way: Its planetary defense program provides funding to a suite of telescopic facilities solely dedicated to identifying potentially hazardous space rocks. (At least, it leads the way for the moment. The White House’s proposal for draconian budget cuts to NASA and the National Science Foundation mean that several observatories and space missions linked to planetary defense are facing funding losses or outright terminations.)

Astronomers working at these observatories are tasked with finding threatening asteroids before they find us—because you can’t fight what you can’t see. “They are the first line of planetary defense,” says Kelly Fast, the acting planetary defense officer at NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office in Washington, DC.

ATLAS is one part of this skywatching project, and it consists of four telescopes: two in Hawaii, one in Chile, and another in South Africa. They don’t operate the way you’d think, with astronomers peering through them all night. Instead, they operate “completely robotically and automatically,” says Denneau. Driven by coding scripts that he and his colleagues have developed, these mechanical eyes work in harmony to watch out for any suspicious space rocks. Astronomers usually monitor their survey of the sky from a remote location.

ATLAS telescopes are small, so they can’t see particularly distant objects. But they have a wide field of view, allowing them to see large patches of space at any one moment. “As long as the weather is good, we’re constantly monitoring the night sky, from the North Pole to the South Pole,” says Denneau.

If they detect the starlight reflecting off a moving object, an operator, such as Denneau, gets an alert and visually verifies that the object is real and not some sort of imaging artifact. When a suspected asteroid (or comet) is identified, the observations are sent to the MPC, which is home to a bulletin board featuring (among other things) orbital data on all known asteroids and comets.

If the object isn’t already listed, a new discovery is announced, and other astronomers can perform follow-up observations.

In just the past few years, ATLAS has detected more than 1,200 asteroids with near-Earth orbits. Finding ultimately harmless space rocks is routine work—so much so that when the new near-Earth asteroid was spotted by ATLAS’s Chilean telescope that December day, it didn’t even raise any eyebrows.

Denneau had simply been sitting at home, doing some late-night work on his computer. At the time, of course, he didn’t know that his telescope had just spied what would soon become a history-making asteroid—one that could alter the future of the planet.

The MPC quickly confirmed the new space rock hadn’t already been “found,” and astronomers gave it a provisional designation: 2024 YR4.

CATALINA SKY SURVEY, ARIZONA

Around the same time, the discovery was shared with another NASA-funded facility: the Catalina Sky Survey, a nest of three telescopes in the Santa Catalina Mountains north of Tucson that works out of the University of Arizona. “We run a very tight operation,” says Kacper Wierzchoś, one of its comet and asteroid spotters. Unlike ATLAS, these telescopes (although aided by automation) often have an in-person astronomer available to quickly alter the surveys in real time.

So when Catalina was alerted about what its peers at ATLAS had spotted, staff deployed its Schmidt telescope—a smaller one that excels at seeing bright objects moving extremely quickly. As they fed their own observations of 2024 YR4 to the MPC, Catalina engineer David Rankin looked back over imagery from the previous days and found the new asteroid lurking in a night-sky image taken on December 26. Around then, ATLAS also realized that it had caught sight of 2024 YR4 in a photograph from December 25.

The combined observations confirmed it: The asteroid had made its closest approach to Earth on Christmas Day, meaning it was already heading back out into space. But where, exactly, was this space rock going? Where would it end up after it swung around the sun?

CENTER FOR NEAR-EARTH OBJECT STUDIES, CALIFORNIA

If the answer to that question was Earth, Davide Farnocchia would be one of the first to know. You could say he’s one of NASA’s watchers on the wall.

And he’s remarkably calm about his duties. When he first heard about 2024 YR4, he barely flinched. It was just another asteroid drifting through space not terribly far from Earth. It was another box to be ticked.

Once it was logged by the MPC, it was Farnocchia’s job to try to plot out 2024 YR4’s possible paths through space, checking to see if any of them overlapped with our planet’s. He works at NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) in California, where he’s partly responsible for keeping track of all the known asteroids and comets in the solar system. “We have 1.4 million objects to deal with,” he says, matter-of-factly.

In the past, astronomers would have had to stitch together multiple images of this asteroid and plot out its possible trajectories. Today, fortunately, Farnocchia has some help: He oversees the digital brain Sentry, an autonomous system he helped code. (Two other facilities in Italy perform similar work: the European Space Agency’s Near-Earth Object Coordination Centre, or NEOCC, and the privately owned Near-Earth Objects Dynamics Site, or NEODyS.)

To chart their courses, Sentry uses every new observation of every known asteroid or comet listed on the MPC to continuously refine the orbits of all those objects, using the immutable laws of gravity and the gravitational influences of any planets, moons, or other sizable asteroids they pass. A recent update to the software means that even the ever-so-gentle push afforded by sunlight is accounted for. That allows Sentry to confidently project the motions of all these objects at least a century into the future.

Almost all newly discovered asteroids are quickly found to pose no impact risk. But those that stand even an infinitesimally small chance of smashing into our planet within the next 100 years are placed on the Sentry Risk List until additional observations can rule out those awful possibilities. Better safe than sorry.

In late December, with just a limited set of data, Sentry concluded that there was a non-negligible chance 2024 YR4 would strike Earth in 2032. Aegis, the equivalent software at Europe’s NEOCC site, agreed. No bother. More observations would very likely remove 2024 YR4 from the Risk List. Just another day at the office for Farnocchia.

It’s worth noting that an asteroid heading toward Earth isn’t always a problem. Small rocks burn up in the planet’s atmosphere several times a day; you’ve probably seen one already this year, on a moonless night. But above a certain size, these rocks turn from innocuous shooting stars into nuclear-esque explosions.

Reflected starlight is great for initially spotting asteroids, but it’s a terrible way to determine how big they are. A large, dull rock reflects as much light as a bright, tiny rock, making them appear the same to many telescopes. And that’s a problem, considering that a rock around 30 feet long will explode loudly but inconsequentially in Earth’s atmosphere, while a 3,000-foot-long asteroid would slam into the ground and cause devastation on a global scale, imperiling all of civilization. Roughly speaking, if you double the size of an asteroid, it becomes eight times more energetic upon impact—so finding out the size of an Earthbound asteroid is of paramount importance.

In those first few hours after it was discovered, and before anyone knew how shiny or dull its surface was, 2024 YR4 was estimated by astronomers to be as small as 65 feet across or as large as 500 feet. An object of the former size would blow up in mid-air, shattering windows over many miles and likely injuring thousands of people. At the latter size it would vaporize the heart of any city it struck, turning solid rock and metal into liquid and vapor, while its blast wave would devastate the rest of it, killing hundreds of thousands or even millions in the process.

So now the question was: Just how big was 2024 YR4?

REFINING THE PICTURE

Mid-January 2025

VERY LARGE TELESCOPE, CHILE

Understandably dissatisfied with that level of imprecision, the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), high up on the Cerro Paranal mountain in Chile’s Atacama Desert, entered the chat. As the name suggests, this flagship facility is vast, and it’s capable of really zooming in on distant objects. Or to put it another way: “The VLT is the largest, biggest, best telescope in the world,” says Hainaut, one of the facility’s operators, who usually commands it from half a world away in Germany.

In reality, the VLT—which lends a hand to the European Space Agency in its asteroid-hunting duties—is actually made up of four massive telescopes, each fixed on four separate corners of the sky. They can be combined to act as a huge light bucket, allowing astronomers to see very faint asteroids. Four additional, smaller, movable telescopes can also team up with their bigger siblings to provide remarkably high-resolution images of even the stealthiest space rocks.

With so much tech to oversee, the control room of the VLT looks a bit like the inside of the Death Star. “You have eight consoles, each of them with a dozen screens. It’s big, it’s large, it’s spectacular,” says Hainaut.

In mid-January, the European Space Agency asked the VLT to study several asteroids that had somewhat suspicious near-Earth orbits—including 2024 YR4. With just a few lines of code, the VLT could easily train its sharp eyes on an asteroid like 2024 YR4, allowing astronomers to narrow down its size range. It was found to be at least 130 feet long (big enough to cause major damage in a city) and as much as 300 feet (able to annihilate one).

January 29, 2025

INTERNATIONAL ASTEROID WARNING NETWORK

By the end of the month, there was no mistaking it: 2024 YR4 stood a greater than 1% chance of impacting Earth on December 22, 2032.

“It’s not something you see very often,” says Marco Fenucci, a near-Earth-object dynamicist at NEOCC. He admits that although it was “a serious thing,” this escalation was also “exciting to see”—something straight out of a sci-fi flick.

Sentry and Aegis, along with the systems at NEODyS, had been checking one another’s calculations. “There was a lot of care,” says Farnocchia, who explains that even though their programs worked wonders, their predictions were manually verified by multiple experts. When a rarity like 2024 YR4 comes along, he says, “you kind of switch gears, and you start being more cautious. You start screening everything that comes in.”

At this point, the klaxon emanating from these three data centers pushed the International Asteroid Warning Network (IAWN), a UN-backed planetary defense awareness group, to issue a public alert to the world’s governments: The planet may be in peril. For the most part, it was at this moment that the media—and the wider public—became aware of the threat. Earth, we may have a problem.

Denneau, along with plenty of other astronomers, received an urgent email from Fast at NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office, requesting that all capable observatories track this hazardous asteroid. But there was one glaring problem. When 2024 YR4 was discovered on December 27, it was already two days after it had made its closest approach to Earth. And since it was heading back out into the shadows of space, it was quickly fading from sight.

Once it gets too faint, “there’s not much ATLAS can do,” Denneau says. By the time of IAWN’s warning, planetary defenders had just weeks to try to track 2024 YR4 and refine the odds of its hitting Earth before they’d lose it to the darkness.

And if their scopes failed, the odds of an Earth impact would have stayed uncomfortably high until 2028, when the asteroid was due to make another flyby of the planet. That’d be just four short years before the space rock might actually hit.

“In that situation, we would have been … in trouble,” says NEOCC’s Fenucci.

The hunt was on.

PREPARING FOR THE WORST

February 5 and February 6, 2025

SPACE MISSION PLANNING ADVISORY GROUP, AUSTRIA

In early February, spaceflight mission specialists, including those at the UN-supported Space Mission Planning Advisory Group in Vienna, began high-level talks designed to sketch out ways in which 2024 YR4 could be either deflected away from Earth or obliterated—you know, just in case.

A range of options were available—including ramming it with several uncrewed spacecraft or assaulting it with nuclear weapons—but there was no silver bullet in this situation. Nobody had ever launched a nuclear explosive device into deep space before, and the geopolitical ramifications of any nuclear-armed nations doing so in the present day would prove deeply unwelcome. Asteroids are also extremely odd objects; some, perhaps including 2024 YR4, are less like single chunks of rock and more akin to multiple cliffs flying in formation. Hit an asteroid like that too hard and you could fail to deflect it—and instead turn an Earthbound cannonball into a spray of shotgun pellets.

It’s safe to say that early on, experts were concerned about whether they could prevent a potential disaster. Crucially, eight years was not actually much time to plan something of this scale. So they were keen to better pinpoint how likely, or unlikely, it was that 2024 YR4 was going to collide with the planet before any complex space mission planning began in earnest.

The people involved with these talks—from physicists at some of America’s most secretive nuclear weapons research laboratories to spaceflight researchers over in Europe—were not feeling close to anything resembling panic. But “the timeline was really short,” admits Hainaut. So there was an unprecedented tempo to their discussions. This wasn’t a drill. This was the real deal. What would they do to defend the planet if an asteroid impact couldn’t be ruled out?

Luckily, over the next few days, a handful of new observations came in. Each helped Sentry, Aegis, and the system at NEODyS rule out more of 2024 YR4’s possible future orbits. Unluckily, Earth remained a potential port of call for this pesky asteroid—and over time, our planet made up a higher proportion of those remaining possibilities. That meant that the odds of an Earth impact “started bubbling up,” says Denneau.

By February 6, they jumped to 2.3%—a one-in-43 chance of an impact.

“How much anxiety someone should feel over that—it’s hard to say,” Denneau says, with a slight shrug.

In the past, several elephantine asteroids have been found to stand a small chance of careening unceremoniously into the planet. Such incidents tend to follow a pattern. As more observations come in and the asteroid’s orbit becomes better known, an Earth impact trajectory remains a possibility while other outlying orbits are removed from the calculations—so for a time, the odds of an impact rise. Finally, with enough observations in hand, it becomes clear that the space rock will miss our world entirely, and the impact odds plummet to zero.

Astronomers expected this to repeat itself with 2024 YR4. But there was no guarantee. There’s no escaping the fact that one day, sooner or later, scientists will discover a dangerous asteroid that will punch Earth in the face—and raze a city in the process.

After all, asteroids capable of trashing a city have found their way to Earth plenty of times before, and not just in the very distant past. In 1908, an 800-square-mile patch of forest in Siberia—one that was, fortunately, very sparsely populated—was decimated by a space rock just 180 feet long. It didn’t even hit the ground; it exploded in midair with the force of a 15-megaton blast.

But only one other asteroid comparable in size to 2024 YR4 had its 2.3% figure beat: in 2004, Apophis—capable of causing continental-scale damage—had (briefly) stood a 2.7% chance of impacting Earth in 2029.

Rapidly approaching uncharted waters, the powers that be at NASA decided to play a space-based wild card: the James Webb Space Telescope, or JWST.

THE JAMES WEBB SPACE TELESCOPE, DEEP SPACE, ONE MILLION MILES FROM EARTH

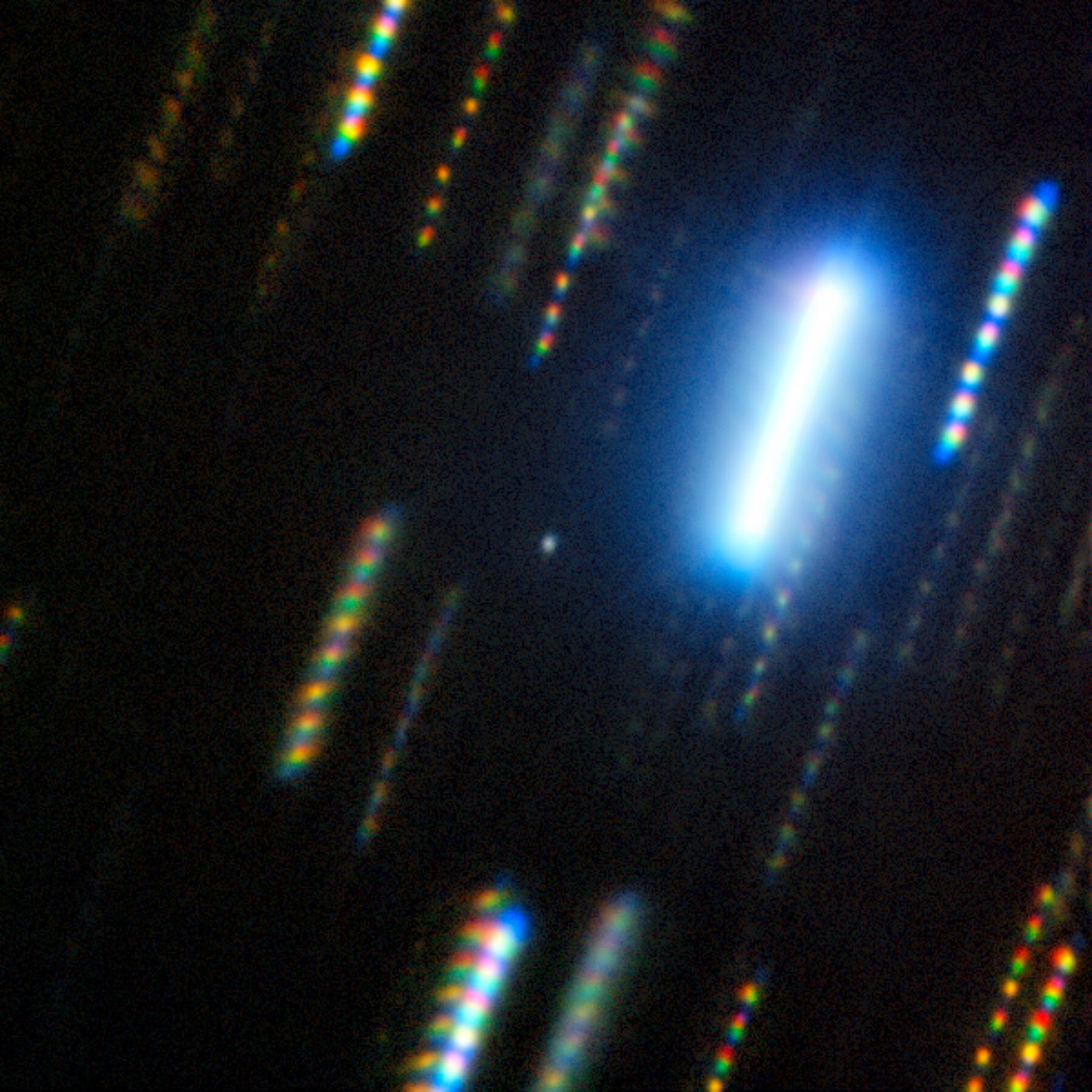

A large dull asteroid reflects the same amount of light as a small shiny one, but that doesn’t mean astronomers sizing up an asteroid are helpless. If you view both asteroids in the infrared, the larger one glows brighter than the smaller one no matter the surface coating—making infrared, or the thermal part of the electromagnetic spectrum, a much better gauge of a space rock’s proportions.

Observatories on Earth do have infrared capabilities, but our planet’s atmosphere gets in their way, making it hard for them to offer highly accurate readings of an asteroid’s size.

But the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), hanging out in space, doesn’t have that problem.

This observatory, which sits at a gravitationally stable point about a million miles from Earth, is polymathic. Its sniper-like scope can see in the infrared and allows it to peer at the edge of the observable universe, meaning it can study galaxies that formed not long after the Big Bang. It can even look at the light passing through the atmospheres of distant planets to ascertain their chemical makeups. And its remarkably sharp eye means it can also track the thermal glow of an asteroid long after all ground-based telescopes lose sight of it.

In a fortuitous bit of timing, by the moment 2024 YR4 came along, planetary defenders had recently reasoned that JWST could theoretically be used to track ominous asteroids using its own infrared scope, should the need arise. So after IAWN’s warning went out, operators of JWST ran an analysis: Though the asteroid would vanish from most scopes by late March, this one might be able to see the rock until sometime in May, which would allow researchers to greatly refine their assessment of the asteroid’s orbit and its odds of making Earth impact.

Understanding 2024 YR4’s trajectory was important, but “the size was the main motivator,” says Andy Rivkin, an astronomer at Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Laboratory, who led the proposal to use JWST to observe the asteroid. The hope was that even if the impact odds remained high until 2028, JWST would find that 2024 YR4 was on the smaller side of the 130-to-300-feet size range—meaning it would still be a danger, but a far less catastrophic one.

The JWST proposal was accepted by NASA on February 5. But the earliest it could conduct its observations was early March. And time really wasn’t on Earth’s side.

February 7, 2025

GEMINI SOUTH TELESCOPE, CHILE

“At this point, [2024 YR4] was too faint for the Catalina telescopes,” says Catalina’s Wierzchoś. “In our opinion, this was a big deal.”

So Wierzchoś and his colleagues put in a rare emergency request to commandeer the Gemini Observatory, an internationally funded and run facility featuring two large, eagle-eyed telescopes—one in Chile and one atop Hawaii’s Mauna Kea volcano. Their request was granted, and on February 7, they trained the Chile-based Gemini South telescope onto 2024 YR4.

The odds of Earth impact dropped ever so slightly, to 2.2% —a minor, but still welcome, development.

Mid-February 2025

MAGDALENA RIDGE OBSERVATORY, NEW MEXICO

By this point, the roster of 2024 YR4 hunters also included the tiny team operating the Magdalena Ridge Observatory (MRO), which sits atop a tranquil mountain in New Mexico.

“It’s myself and my husband,” says Eileen Ryan, the MRO director. “We’re the only two astronomers running the telescope. We have a daytime technician. It’s kind of a mom-and-pop organization.”

Still, the scope shouldn’t be underestimated. “We can see maybe a cell-phone-size object that’s illuminated at geosynchronous orbit,” Ryan says, referring to objects 22,000 miles away. But its most impressive feature is its mobility. While other observatories have slowly swiveling telescopes, MRO’s scope can move like the wind. “We can track the fastest objects,” she says, with a grin—noting that the telescope was built in part to watch missiles for the US Air Force. Its agility and long-distance vision explain why the Space Force is one of MRO’s major clients: It can be used to spy on satellites and spacecraft anywhere from low Earth orbit right out to the lunar regions. And that meant spying on the super-speedy, super-sneaky 2024 YR4 wasn’t a problem for MRO, whose own observations were vital in refining the asteroid’s impact odds.

Then, in mid-February, MRO and all ground-based observatories came up against an unsolvable problem: The full moon was out, shining so brightly that it blinded any telescope that dared point at the night sky. “During the full moon, the observatories couldn’t observe for a week or so,” says NEOCC’s Fenucci. To most of us, the moon is a beautiful silvery orb. But to astronomers, it’s a hostile actor. “We abhor the moon,” says Denneau.

All any of them could do was wait. Those tracking 2024 YR4 vacillated between being animated and slightly trepidatious. The thought that the asteroid could still stand a decent chance of impacting Earth after it faded from view did weigh a little on their minds.

Nevertheless, Farnocchia maintained his characteristic sangfroid throughout. “I try to stress about the things I can control,” he says. “All we can do is to explain what the situation is, and that we need new data to say more.”

February 18, 2025

CENTER FOR NEAR-EARTH OBJECT STUDIES, CALIFORNIA

As the full moon finally faded into a crescent of light, the world’s largest telescopes sprang back into action for one last shot at glory. “The dark time came again,” says Hainaut, with a smile.

New observations finally began to trickle in, and Sentry, Aegis, and NEODyS readjusted their forecasts. It wasn’t great news: The odds of an Earth impact in 2032 jumped up to 3.1%, officially making 2024 YR4 the most dangerous asteroid ever discovered.

This declaration made headlines across the world—and certainly made the curious public sit up and wonder if they had yet another apocalyptic concern to fret about. But, as ever, the asteroid hunters held fast in their prediction that sooner or later—ideally sooner—more observations would cause those impact odds to drop.

“We kept at it,” says Ryan. But time was running short; they started to “search for out-of-the-box ways to image this asteroid,” says Fenucci.

Planetary defense researchers soon realized that 2024 YR4 wasn’t too far away from NASA’s Lucy spacecraft, a planetary science mission making a series of flybys of various asteroids. If Lucy could be redirected to catch up to 2024 YR4 instead, it would give humanity its best look at the rock, allowing Sentry and company to confirm or dispel our worst fears.

Sadly, NASA ran the numbers, and it proved to be a nonstarter: 2024 YR4 was too speedy and too far for Lucy to pursue.

It was really starting to look as if JWST would be the last, best hope to track 2024 YR4.

A CHANGE OF FATE

February 19, 2025

VERY LARGE TELESCOPE, CHILE and MAGDALENA RIDGE OBSERVATORY, NEW MEXICO

Just one day after 2024 YR made history, the VLT, MRO, and others caught sight of it again, and Sentry, Aegis, and NEODyS voraciously consumed their new data.

The odds of an Earth impact suddenly dropped to 1.5%.

Astronomers didn’t really have time to react to the possibility that this was a good sign—they just kept sending their observations onward.

February 20, 2025

SUBARU TELESCOPE, HAWAII

Yet another observatory had been itching to get into the game for weeks, but it wasn’t until February 20 that Tsuyoshi Terai, an astronomer at Japan’s Subaru Telescope, sitting atop Mauna Kea, finally caught 2024 YR4 shifting between the stars. He added his data to the stream.

And all of a sudden, the asteroid lost its lethal luster. The odds of its hitting Earth were now just 0.3%.

At this point, you might expect that all those tracking it would be in a single control room somewhere, eyes glued to their screens, watching the odds drop before bursting into cheers and rapturous applause. But no—the astronomers who had spent so long observing this asteroid remained scattered across the globe. And instead of erupting into cheers, they exchanged modestly worded emails of congratulations—the digital equivalent of a nod or a handshake.

“It was a relief,” says Terai. “I was very pleased that our data contributed to put an end to the risk of 2024 YR4.”

February 24, 2025

INTERNATIONAL ASTEROID WARNING NETWORK

Just a few days later, and thanks to a litany of observations continuing to flood in, IAWN issued the all-clear. This once-ominous asteroid’s odds of inconveniencing our planet were at 0.004%—one in 25,000. Today, the odds of an Earth impact in 2032 are exactly zero.

“It was kinda fun while it lasted,” says Denneau.

Planetary defenders may have had a blast defending the world, but these astronomers still took the cosmic threat deeply seriously—and never once took their eyes off the prize. “In my mind, the observers and orbit teams were the stars of this story,” says Fast, NASA’s acting planetary defense officer.

Farnocchia shrugs off the entire thing. “It was the expected outcome,” he says. “We just didn’t know when that would happen.”

Looking back on it now, though, some 2024 YR4 trackers are allowing themselves to dwell on just how close this asteroid came to being a major danger. “It’s wild to watch it all play out,” says Denneau. “We were weeks away from having to spin up some serious mitigation planning.” But there was no need to work out how the save the world. It turned out that 2024 YR4 was never a threat to begin with—it just took a while to check.

And these experiences in handling a dicey space rock will only serve to make the world a safer place to live. One day, an asteroid very much like 2024 YR4 will be seen heading straight for Earth. And those tasked with tracking it will be officially battle-tested, and better prepared than ever to do what needs to be done.

A POSTSCRIPT

March 27, 2025

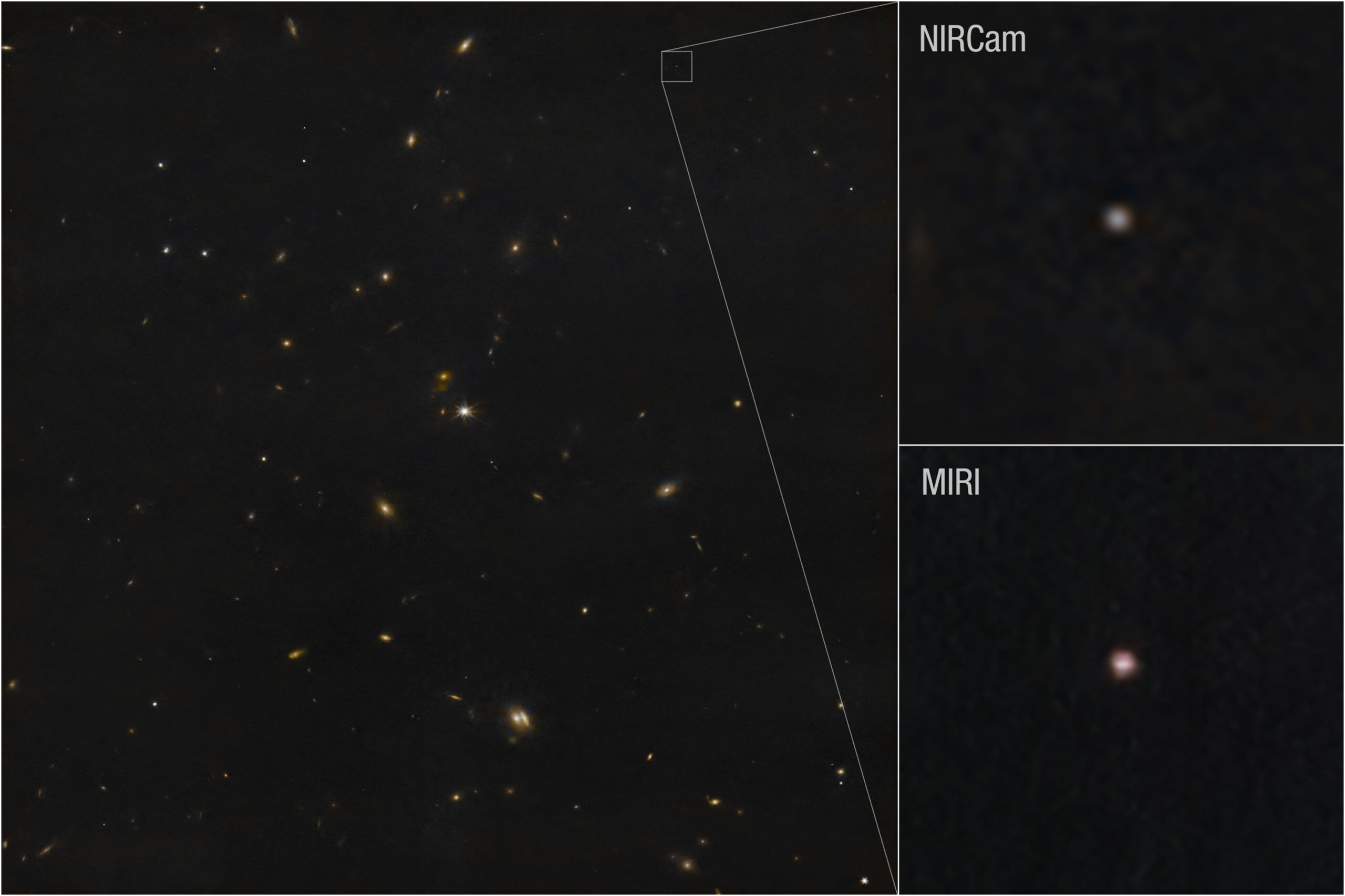

JAMES WEBB SPACE TELESCOPE, DEEP SPACE, ONE MILLION MILES FROM EARTH

But the story of 2024 YR4 is not quite over—in fact, if this were a movie, it would have an after-credits scene.

After the Earth-impact odds fell off a cliff, JWST went ahead with its observations in March anyway. It found out that 2024 YR4 was 200 feet across—so large that a direct strike on a city would have proved horrifically lethal. Earth just didn’t have to worry about it anymore.

But the moon might. Thanks in part to JWST, astronomers calculated a 3.8% chance that 2024 YR4 will impact the lunar surface in 2032. Additional JWST observations in May bumped those odds up slightly, to 4.3%, and the orbit can no longer be refined until the asteroid’s next Earth flyby in 2028.

“It may hit the moon!” says Denneau. “Everybody’s still very excited about that.”

A lunar collision would give astronomers a wonderful opportunity not only to study the physics of an asteroid impact, but also to demonstrate to the public just how good they are at precisely predicting the future motions of potentially lethal space rocks. “It’s a thing we can plan for without having to defend the Earth,” says Denneau.

If 2024 YR4 is truly going to smash into the moon, the impact—likely on the side facing Earth—would unleash an explosion equivalent to hundreds of nuclear bombs. An expansive crater would be carved out in the blink of an eye, and a shower of debris would erupt in all directions.

None of this supersonic wreckage would pose any danger to Earth, but it would look spectacular: You’d be able to see the bright flash of the impact from terra firma with the naked eye.

“If that does happen, it’ll be amazing,” says Denneau. It will be a spectacular way to see the saga of 2024 YR4—once a mere speck on his computer screen—come to an explosive end, from a front-row seat.

Robin George Andrews is an award-winning science journalist and doctor of volcanoes based in London. He regularly writes about the Earth, space, and planetary sciences, and is the author of two critically acclaimed books: Super Volcanoes (2021) and How to Kill An Asteroid (2024).