The new US border wall is an app

A few minutes before 9 a.m. on a day in late March, Keisy Plaza, 39, leans against a wall on the corner of Juárez Avenue and Gardenias Street in Ciudad Juárez. It’s the last intersection before Mexico turns into El Paso, Texas, and a stream of commuters drive past on their way to work and other daily activities that intertwine the two border cities.

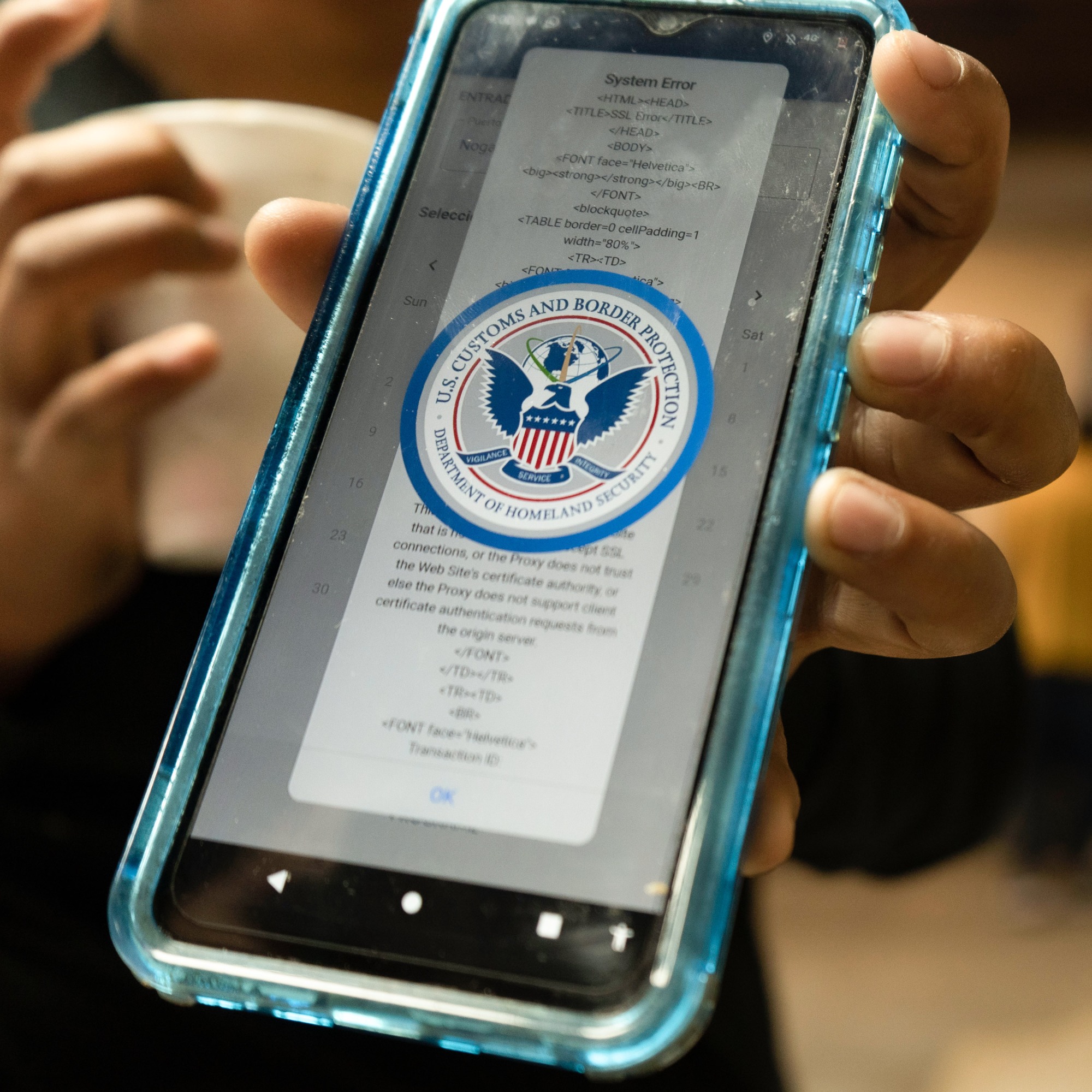

I first met Plaza in a small, crowded shelter a few feet away from the border wall. Originally from Venezuela, she had left her home in Colombia seven months before. She walked a 62-mile stretch of dense mountainous rainforest and swampland called the Darién Gap with two small children and crossed several countries on foot and atop train cars to get to this corner. Her destination is just a few feet away. But instead of walking over to the bridge that serves as an official border crossing and asking for protection in the United States, she just stands there with her 20-year-old daughter, both glued to their phones, as her seven-year-old daughter and three-year-old grandson cry for breakfast and attention. Plaza has been trying every day for weeks to secure an appointment with Customs and Border Protection (CBP) so she can request permission for her family of five to enter the US. So far, she’s had no luck: each time, she’s been met with software errors and frozen screens. When appointment slots do open up, they fill within minutes.

Plaza has not been the only person to encounter this new obstacle to finding refuge in the United States. At the start of this year, President Biden announced that people at the southern border who want to seek asylum in the US must first request an appointment to meet with an immigration official via a mobile app. The app, called CBP One, had been used by the US Department of Homeland Security since 2020, to let travelers send their information in advance and speed up processing at a port of entry. But in January, the department expanded the app’s use to include people without documentation who are seeking protection from violence, poverty, or persecution. At the time, Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro N. Mayorkas said it was poised to become “one of the many tools and processes this administration is providing for individuals to seek protection in a safe, orderly, and humane manner and to strengthen the security of our borders.”

In the months since, the app has only become more entrenched. On May 11, the US government lifted a pandemic-era public health policy called Title 42 that for a few years enabled officials to rapidly expel migrants from the US. CBP One, which since January had been used to process humanitarian exemptions to the policy, stayed. It is one of just a handful of legal pathways for people seeking protection to enter the US (they may be allowed in if they have been denied asylum in another country, and there is a program that allows successful applicants from Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to fly in directly). At the same time, DHS is implementing harsher consequences for people who don’t use these pathways. Under a new regulation, those who enter the US unlawfully are ineligible for asylum, with few exceptions. The policy so tightly restricts avenues for legal entry that many immigrant rights groups in the US have called it an “asylum ban.”

“Can you imagine the toll it takes psychologically, thinking every day, ‘Maybe today is the day’?”

Brian Strassburger

For years, the number of migrants and asylum seekers arriving at the southern border seeking protection has been more than what the US government can process at ports of entry. They often wait in precarious places—border cities like Ciudad Juárez, Tijuana, Reynosa, and Matamoros, where shelters are often at full capacity and migrants are exposed to kidnapping, extortion, and other dangers. Many people are homeless, with no running water, no electricity, no access to school or educational programs for kids, and no guarantee of a hot meal. “Mexico doesn’t recognize this as a humanitarian crisis, but in my opinion, it is a migration crisis that requires resources, services, and a humanitarian response plan,” says Rafael Velásquez, Mexico director of the International Rescue Committee, an organization that helps people affected by crises around the world.

The app essentially adds one more stop—this time a digital one—in people’s migration route to the US. With a few exceptions, migrants can no longer approach a US immigration officer at the southern border or turn themselves in after crossing to seek protection. Now, they’re supposed to make an appointment online to present at the border if they want their internationally recognized right to seek asylum in the US upheld. But getting an appointment, for many people, has been as challenging as trying to buy a ticket to a Taylor Swift concert on Ticketmaster.

No one who uses the app knows how long the wait will be. In late May, I caught up with Brian Strassburger, a Jesuit priest who visits shelters and migrant encampments in the Mexican border state of Tamaulipas. He knew people who had been using CBP One since the first week of March and still didn’t have an appointment. “They use it every single day,” he said, “so that’s three months of daily stress, of saying, ‘Is today the day I am going to win this lottery?’ Can you imagine the toll it takes psychologically, thinking every day, ‘Maybe today is the day’?”

Although CBP has expanded the number of appointments available each day on the app and addressed a number of technical issues, immigration rights activists argue that the software itself, no matter how efficient or error-free it becomes, is an unacceptable barrier. To use it, people need a compatible mobile device. They also need a strong internet connection, resources to pay for data, electricity to charge their devices, tech literacy, and other conditions that place the most vulnerable migrants at a disadvantage.

“Technology is not policy, and no matter how many fixes they make to the app … it’s still not a sufficient system for people running for their lives,” says Bilal Askaryar, the interim campaign manager for #WelcomeWithDignity, a coalition of organizations, activists, and asylum seekers that advocates for the rights of immigrants and refugees. “The issue isn’t the glitches and the bugs. The issue is the app itself. That people must have an app to request protection is misunderstanding the dire situation these people are in.”

DHS maintains that while the situation at the border is challenging and difficult, the department is sticking with its strategy of discouraging people from attempting unauthorized crossings. At the same time, it is making more and more CBP One appointments available: at the beginning of June, the department expanded the number of available slots to 1,250 per day, up from about 750 when the program started. “We have a plan; we are executing on that plan,” Mayorkas said on May 5. “Fundamentally, however, we are working within a broken immigration system that for decades has been in dire need of reform.”

Immigrant rights groups are mounting legal challenges to the latest policy changes. But while the new rule stands, people contemplating crossing the southern border must make a choice: roll the dice to see if they can enter the country officially, apply for asylum in a country they do not want to settle in (which would make them ineligible to apply in the US), or put their lives at risk by attempting to cross unlawfully.

In late March, thousands of migrants and asylum seekers wandered the streets of downtown Ciudad Juárez, passing time, washing windshields at red lights, and selling candy on the streets. Others charged their phones at one of a handful of free charging stations near the National Women’s Institute downtown, waited in line to enter a food kitchen, or watched as their children played, distancing themselves from the grownups’ troubles.

Not far from where Plaza was standing, Óscar Fuentes approached a woman selling empanadas to ask her what she had heard from her usual customers. “No appointments,” she replied. Fuentes, who is from Colombia, had been in Juárez for two months. He was renting a small room that he shared with 28 other people, but he counted himself lucky. “Think of all the people that are staying in places that we can’t see,” he said.

Mexico is a dangerous place. More than 100,000 people have disappeared since 1964, most during the state’s war on drugs that started in 2006. Migrants making their way through the country are especially vulnerable: they risk being kidnapped, extorted, robbed, and murdered along their journey. Those who do make it to the border are not out of danger. On January 26, for example, a 17-year-old from Cuba was shot to death in a hotel in the northern city of Monterrey while waiting for a scheduled appointment. Days later, a 15-year-old Haitian boy died in a Reynosa rental house waiting for an appointment slot, according to local media.

People seeking asylum in the US don’t have an immigration status in Mexico that would allow them to seek formal employment in the country. Some are picked up off the streets by Mexican immigration officials and detained in facilities that pose dangers of their own. In March, 40 migrants awaiting deportation died in a fire at an immigration detention center in Ciudad Juárez.

US government officials say that CBP One is achieving its purpose. Instead of trying to cross unlawfully, people waiting at the border are opting to try for a sanctioned passage. Monthly encounters between CBP and people trying to enter without authorization, which reached record highs in 2022, decreased to around 128,877 in January—the first decline since February 2021. The number has increased since then, but it is still lower than in previous years.

But CBP says it can only process so many people in a day. “We have an operational capacity at ports of entry because we are balancing legitimate trade and travel and other enforcement missions,” a CBP official told MIT Technology Review in April. He explained that the agency is making sure the billions of dollars’ worth of trade that crosses from Mexico into the US is processed smoothly, while still working to catch drug and weapon smuggling: “We have to balance our finite resources.”

“That people must have an app to request protection is misunderstanding the dire situation these people are in.”

Bilal Askaryar

For those waiting at the border, however, the app represents another chapter in an already rocky story. For many years, the backlog at the border was managed through metering—a simple limit on the number of people who would be accepted for processing. Over time, as US policy shifted, Mexican government officials and civil society organizations began creating informal wait lists to organize the queues of people in Mexican border cities who wanted to seek asylum in the US.

Then, in March 2020, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued an order under Title 42 of the US code of laws, expediting expulsions, halting the processing of asylum claims at ports of entry, and blocking entry for individuals without valid travel documents. After lawyers and activists filed suit in 2021, the government introduced exceptions that allowed people to request permission to enter the US on humanitarian grounds. Those with a physical or mental illness or disability were potentially eligible for an exception, as were those who lacked safe housing or shelter in Mexico, faced threats of harm there, or were under 21, over 70, or pregnant.

The number of people seeking Title 42 exceptions surpassed CBP’s number of daily slots, and the wait lists created by nonprofit organizations grew and proliferated. As of August of last year, there were over 55,000 people on Title 42 exception wait lists across different border cities, according to research by the Strauss Center for International Security and Law. Since January, use of CBP One has eliminated the wait lists. But the backlog—and the protracted waits—have continued. Mexican officials and civil society organizations don’t keep track of the numbers, but there could be around 660,000 migrants in Mexico, according to United Nations figures cited by the acting CBP commissioner, Troy Miller. Shelters regularly reach full capacity, and wait times are proving to be long.

The wait-list framework was far from perfect: it was susceptible to fraud, extortion, and the poor judgment of people managing the lists. Still, it was a more humane policy because it was up to people to decide who was eligible for an exception, says Thiago Almeida, head of the Ciudad Juárez field office for the United Nations’ International Organization for Migration, an intergovernmental organization that works to ensure the orderly and humane management of migration. With the app, there’s no way to prioritize those most in need. “People who have better access to technology, know how to use it, and have access to faster internet have a better chance to get an appointment,” he says.

When I spoke with Strassburger in March, he said CBP was effectively “beta-testing the app on people in vulnerable situations.” In the first few months after the rollout of the appointment system, advocates quickly identified problems that made the app difficult or almost impossible to use.

At first, for example, it was available only in English and Spanish, leaving out migrants who speak Haitian Creole, Indigenous languages, and more. Organizations working with migrants also flagged serious issues with the app’s facial recognition feature, which is used to establish that the software is interacting with a real person and not a bot or malicious software.Many people with darker skin tones found that the app failed to register their faces.

The facial recognition feature began improving with CBP One’s update at the end of February, says Felicia Rangel-Samponaro, director of Sidewalk School, an organization that provides shelter and educational services to migrants and asylum seekers in Tamaulipas. Sidewalk School works with a large population of Haitian migrants and has been calling out the app’s biases against this population from the start. “This whole time, Black people have been left out [of the process],” she says. “That’s crazy!”

“A lot of the difficulties with live photos have to do with the quality of the image, not with the algorithm looking at those photos,” said the CBP official who spoke with MIT Technology Review. To eliminate some of those problems, CBP decreased the number of live photos required per application, reducing the data bandwidth needed and allowing for a smoother experience with this function. “We saw an increase in the expediency in which someone was able to access the application from when we originally started doing it,” he said.

The International Organization for Migration surveyed migrants in Tamaulipas and found that the app seemed to present more issues on Huawei phones. Rumors abounded about potential fixes. Some migrants believed the iPhone’s iOS system works better than Android and that older versions of the app worked better than the most recent updates. When I asked the CBP official about these discussions in April, he said that hardware shouldn’t be an issue. “You just have to have your device updated to the most recent software,” he said.

Those with hardware that works still need a broadband internet connection to use the app. The Wi-Fi connections in shelters, migrant camps, and hotels are spotty and slow down considerably when hundreds of people try to connect at once. Many migrants buy cellular data instead, spending between 50 and 100 pesos ($2.50 to $5) a day.

At first, even with a good connection, people faced issues with frozen screens, confirmation emails that never arrived, log-in failures, and errors with the app’s GPS location data. The app tracks users’ location and is designed to work only in central and northern Mexico. Yet some people within range were having issues with this feature; they got error messages indicating that they were too far from a port of entry.

“No one lends their phone here, since everyone is on the lookout for their appointments.”

Norkys A

By May, Strassburger says, CBP had addressed many of the issues that came with connectivity limitations, but that hasn’t eliminated all barriers. “The app has gotten to a much better place in terms of its functionality,” he says, “but the US government has done everything in its power to funnel people to use the app as their one way of crossing, and yet they have not made it an adequately sufficient avenue.”

There are still not enough appointments given the number of people “who are waiting and living in really inhumane conditions,” he says, often facing safety risks in Mexico. The need for a working smartphone with enough battery charge and a good internet connection is “an expense they are having to make as a family, prioritizing that over food on any given day,” he adds. “That continues to be a decision they have to make.”

In the first months after the CBP One app was introduced to make appointments for entry applications, all the slots available for the day opened up at 6 a.m. Pacific time. But people logged in hours earlier. “People are waking up at 3 a.m. these days, because they have to get into that app early. Otherwise the bandwidth overflows and they don’t get their text confirmation to log in,” Strassburger said at the time.

On May 5, on top of the increase in daily appointments, CBP announced changes to the app that will give users additional time to complete the appointment request. A big source of problems and anxiety for migrants came at this stage of the process, because people had only minutes to confirm their slot—if they were lucky enough to get one—by submitting a photo. If the app had trouble reading the photo or bandwidth problems prevented them from uploading it, time could quickly run out. This happened to Plaza several times. Each time, she says, she was devastated by getting so close but failing.

Now, instead of making appointments available at the same time each day for a short period, the scheduling system will let people make requests and confirm appointments in two separate steps over the course of two days, essentially giving them a “longer window of time to ask for and to confirm their appointment” and reducing “time pressure and dependency on internet speed and connectivity,” according to a CBP press release announcing the change. CBP also stated that it will work to prioritize people who have waited the longest.

“It’s taken five months and a lot of mistakes, but I think they have made the system better,” says Strassburger. “I just wish they had run way more tests and gone through it a lot more thoroughly so that this sort of procedure had launched in January, as opposed to all the stress and trauma that people were put through because of all the missteps along the way.”

As of late May, migrants and asylum seekers had managed to schedule more than 122,000 appointments at points of entry along the southern border, according to CBP. Many people are still crossing into the US on their own: in April, CBP encountered 182,114 people entering unlawfully between those ports of entry, up 12% from the number a month before. Nevertheless, though the Biden administration expected a big increase in migrants and asylum seekers at the border upon the end of Title 42 on May 11, that didn’t happen. The government’s increased restrictions and enforcement policies targeting unlawful migration appear to be deterring people from crossing without authorization and encouraging them to use the CBP One app instead.

While some people might get an appointment through CBP One on their first attempt, others may try for weeks or months, depending on their circumstances and their luck. Norkys A., a single mother who left to support her family and church in Venezuela, tried for months to get an appointment in Ciudad Juárez after she arrived on December 26, 2022, with her two teenage children. By March, they were living in a shelter and barely going out. “This confinement is driving us crazy,” she said, speaking from a little nook in the attic where she slept. Backpacks hung from hooks on the walls, and the floors were made of plywood. A few old toys were scattered around for children to play with. “I want to get to the US so my children can start going to school,” she said.

Norkys broke her shoulder while hopping trains to get to Ciudad Juárez. She visited a local clinic, which prescribed painkillers and told her she needs surgery that would cost about $5,000. She didn’t have that kind of money; she didn’t even have enough for a sling to immobilize her arm. Nor did she have a working phone to use CBP One. “I left without a cell phone, money, and food,” she explained. She occasionally tried for an appointment with a borrowed phone, if she could find one. “No one lends their phone here, since everyone is on the lookout for their appointments,” she said. “Their goal is getting across.”

of the Cathedral of Ciudad Juárez

a makeshift shelter

and children rest in a makeshift

shelter

Plaza says that when she was staying in a shelter in Ciudad Juárez in March, she tried the app practically every day, never losing hope that she and her family would eventually get their chance. Seven weeks after arriving in the city, she got her CBP One appointment, at the Paso del Norte port of entry in El Paso, and slowly made her way north to her destination, where she will settle while she awaits her day in immigration court next year.

Not everyone is choosing to wait. After four months in Ciudad Juárez, Norkys and her two children crossed into the US unlawfully on April 25. They were detained and deportation proceedings were begun, but they were released in Laredo, Texas, and will have the opportunity to appear in court to present their case in an immigration hearing in the near future. While she waits, Norkys is trying to settle into life in the US, relying on shelters and charities to get on her feet. The future remains uncertain, but she is grateful. “As long as we are alive and healthy,” she says, “all is good.”

Lorena Ríos is a freelance journalist based in Monterrey, Mexico.