Finding forgotten Indigenous landscapes with electromagnetic technology

ONE

Jarrod Burks opened the rear cargo door of his van and pointed to an array of strange equipment tangled inside. White PVC tubes were locked together, forming an expandable, fence-like grid, with large, rugged wheels attached beneath. Beside it all, on a layer of soft blankets, were a tablet computer, many yards of cables, and a GPS antenna, held in a small protective case. Properly assembled, Burks explained, this was a magnetometer—a device for measuring tiny fluctuations in Earth’s magnetic field. It is a tool so finicky that interference from a cell phone in his jeans pocket can ruin an entire day’s data, so sensitive that it can pick up traces of ancient campfires extinguished more than a thousand years ago.

Burks, 50, sporting a closely trimmed, graying beard and a pair of rectangular eyeglasses, began hauling his mix of parts outside, where he would piece them together on the dew-covered grass. Emblazoned on the side of his van was the logo of Ohio Valley Archaeology, Inc. (OVAI), a privately owned cultural-resource management firm based in Columbus, the state capital. Burks has worked full time at OVAI since 2004, shortly after earning his PhD in archaeology from Ohio State University; he is now its director of archaeological geophysics. In addition to performing site surveys throughout the Midwest and abroad—including congressionally funded trips to map overseas battlefields, where he searches for the remains of US soldiers—Burks is president of the Heartland Earthworks Conservancy, dedicated to “advancing the preservation of ancient earthworks in southern Ohio.” By using one of the most advanced geophysical tools on the market, Burks is helping to reveal—and thus preserve—forgotten monuments of explosively creative cultures, groups that not only were capable of large-scale architectural engineering but thoroughly reshaped the North American landscape.

The fertile river valleys of the American Midwest hide tens of thousands of indigenous earthworks, according to Burks: geometric structures consisting of walls, mounds, ditches, and berms, some dating back nearly 3,000 years. They can take the form of giant circles and squares, cloverleafs and octagons, complex S-curves and simple mounds. Some are so enormous that, ironically, they are difficult to spot, more closely resembling natural landforms than works of architecture. Others are so small they at first seem to be little more than unkempt mounds of grass. Many of these structures also appear to be aligned with significant constellations or celestial events such as lunar cycles, implying the existence of sophisticated, multigenerational astronomical knowledge as well as a large, politically organized workforce dedicated to realizing a set of beliefs in physical form. Archaeologists now believe that the earthworks functioned as religious gathering places, tombs for culturally important clans, and annual calendars, perhaps all at the same time.

archaeologist Jarrod Burks is mapping the lost cultures of southern Ohio.

Although monumental earthworks can be found from southern Canada to Florida and from Wisconsin to Louisiana, Ohio has the largest known collection of these structures in the United States—despite the fact that Ohio has no federally recognized Native American tribes. Their creators have been lumped together under a vague term, “Hopewell Culture,” named after the family on whose farmland one of the first mounds to be studied was found. Cultural activities associated with the Hopewell are thought to have ended in the Ohio region around 450 to 400 BCE. Tribes such as the Eastern Shawnee, the Miami Nation, and the Shawnee—who, historians believe, are the mound builders’ most likely modern descendants—were violently displaced by the European genocide of the continent’s native population and now live on reservation lands in Oklahoma.

Glenna Wallace, chief of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe, is one of those descendants. When we spoke, Wallace was on her way to Washington, DC, to meet President Joe Biden for the White House Tribal Nations Summit. These annual events were first convened in 2009 by President Barack Obama but were discontinued during the Trump administration. Wallace had only recently returned from southern Ohio, where she had been visiting sites associated with her tribe’s ancient roots. “The Native American voice has not been very strong in Ohio. The things that our people accomplished there have not necessarily received the best protection that should be possible,” she told me. “The people have been forced to leave, and our mounds have not been taken care of.”

Burks and I had driven roughly 70 miles southeast from Columbus, along meandering highways lined with creeks and roadkill, to reach a small family farm in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains. The trees around us were crisp with autumn leaves. A herd of cattle wandered past, their muscular backs framed against rolling hills in the distance. As Burks completed the 20-minute process of assembling his magnetometer—once complete, it would form a pushcart nearly seven feet wide, weighing roughly 30 pounds—he emphasized that the vast majority of the artificial hills and mounds he spends his time looking for were physically dismantled long ago. In only a few cases were those earthworks first excavated or studied; instead, they were simply plowed over; bulldozed to build roads, homes, and shopping malls; or, in one infamous case, incorporated into the landscaping of a local golf course.

Archaeologists believe that these earthworks functioned as religious gathering places, tombs for culturally important clans, and annual calendars, perhaps all at the same time.

Until recently, it seemed as if much of the continent’s pre-European archaeological heritage had been carelessly wiped out, uprooted, and lost for good. “People see plowing and think it’s completely destroyed the archaeological record here,” Burks said, “but it’s still there.” Traces remain: electromagnetic remnants in the soil that can be detected using specialty surveying equipment. Here, in this very pasture, he added, were once at least three circular enclosures. Our goal that morning was to find them.

Magnetometry—Burks’s specialty—is capable of registering even tiny variations in the strength and orientation of magnetic fields. When pushed across the landscape, a magnetometer can detect where those fields in the soil below have changed, potentially indicating the presence of an object or structure such as old walls, metallic implements, or filled-in pits that might be graves. Magnetometry is also extremely good at finding hearths or campfires, whose heat can permanently alter the magnetism of the soil, leaving behind a clearly detectable signature. This means that even apparently empty pastures—or, of course, community golf courses and suburban backyards—can still contain magnetic evidence of ancient settlements, invisible to the naked eye.

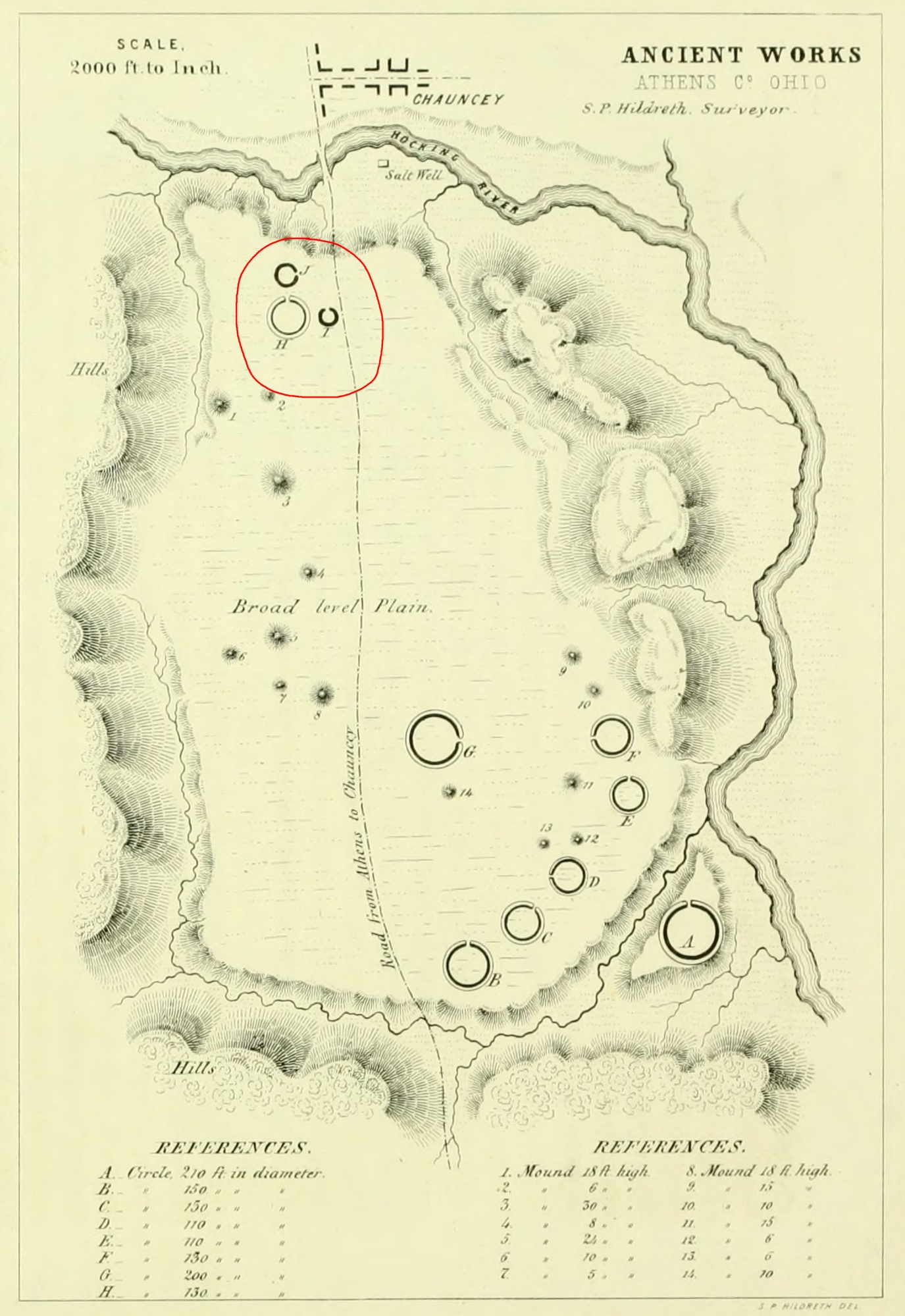

Given such a context, knowing where to begin scanning is the first hurdle. Luckily for archaeologists and tribal historians alike, Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis—a two-man team working in the middle of the 19th century—mapped as many earthworks as they could find, motivated to learn more about these artificial landforms before they were destroyed or permanently forgotten. Explaining their project’s rationale, the authors wrote that the earthworks had received only passing descriptions in other travelers’ logs and, they thought, “should be more carefully and minutely, and above all, more systematically investigated.” Doing so, they hoped, was their way of “reflecting any certain light upon the grand archaeological questions connected with the primitive history of the American Continent.”

in Athens County, Ohio,

from Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley by Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis.

of the artificial hills and mounds Burks spends his time looking

for were physically

dismantled long ago.

The result was an 1848 publication called Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. That book has the distinction of being the first major publication of the Smithsonian Institution, founded a mere two years earlier, in 1846. While it lacks the rigor and precision of a modern survey, the book is historically invaluable, offering a snapshot of where the grandest earthworks once stood.

One of those was Shriver Circle, named after Henry Shriver, a 19th-century landowner, and located just north of Chillicothe, Ohio. One of only four known “great circles”—enormous enclosures, as wide as 1,300 feet in diameter—it could once have held thousands of people. Squier and Davis wrote that the circle “has a mound, very nearly if not exactly in its center, which was clearly a place of sacrifice.” Today, a four-lane highway runs through it and a medium-security correctional facility smothers its outer rim. While this is archaeologically tragic, it was also, for Burks, a great opportunity to push magnetometry to its limit. He received permission to bring his equipment into the prison, scanning the ground beneath cell blocks and concrete exercise yards for magnetic evidence of one of North America’s largest indigenous architectural feats. The effort was successful: most of Shriver Circle may be invisible on the surface, but its deeper roots remain.

Burks continues to uncover and map new sites throughout Ohio and Indiana, regularly convening with a small group of colleagues to pore through aerial photos taken over many decades by the US Department of Agriculture. One attendee of these informal research meetings has risen to the task so enthusiastically that he often texts Burks late at night, claiming to have found something—a shadow, a ridge, an unexpected form—in the old images. “He has earthworks fever, like I do,” Burks joked. He credits this colleague with identifying only the fourth known great circle in the state of Ohio, a landform unknown even to Squier and Davis.

Back in the field outside Columbus, Burks ran a few diagnostic tests, ensuring that his gear was up and running. Then we set off, pushing his magnetometry cart between groups of baffled cattle, hoping to find electromagnetic ghosts of indigenous archaeology trapped in the ground below.

TWO

One of the unforeseen consequences of archaeology’s electromagnetic turn is that the makers of technical equipment such as Burks’s magnetometer now have immense influence over the kinds of archaeological sites that can be found—even how they can be seen. Those firms thus also steer what we can know of human history. A seemingly minor decision made while designing antennas or producing new software can cause certain architectural ruins to remain unknown or undetected—if, for example, the equipment is badly shielded, and thus vulnerable to interference—or, conversely, can lead to breakthroughs at sites once thought worthless, thanks to increased computational power that makes it possible to analyze noisy data.

To see how magnetometry equipment is designed and made, I traveled to the global headquarters of Sensys, makers of Burks’s own device. Sensys is located in a converted East German telephone building on a wooded plot of land roughly 25 miles from Berlin. A large promotional sign mounted on one wall says, in English, “We measure. Detect. Protect.” A decommissioned satellite dish remains intact atop the circular building, which was in the midst of an extensive upgrade and renovation when I visited. I was met by Gorden Konieczek, a technician specializing in archaeological applications. As we sat down at a table generously stocked with coffee, spring water, and German sweets, Konieczek joked that the company’s headquarters are so remote employees are out of luck if they forget to bring lunch; but it is precisely this isolation, largely free from electromagnetic disturbance, that makes it ideal for producing magnetometers.

“When people see these earthworks, they begin to understand that these were incredibly intelligent people who did amazing things.”

Diane Hunter, tribal historic preservation officer

Nevertheless, Konieczek said, even a location such as this has its own magnetic environment, with background levels that must be accounted for and controlled. When Sensys installed a new emergency fire staircase on the back of the building, he explained, it sent the company’s instruments into a brief tailspin, throwing off readings until technicians could troubleshoot the cause. The equipment itself must also be calibrated outside the main facility, inside a purpose-built structure resembling an Alpine hunting lodge in design. This hut—or “Abgleich Haus,” as it’s known, roughly translated as calibration house—was constructed using all-wooden joints and nonmagnetic nails, so as not to interfere with sensitive equipment readings.

Burks’s magnetometer measures tiny fluctuations in Earth’s magnetic field. The tool is so finicky that interference from a cell phone in his jeans pocket can ruin an entire day’s data and so sensitive that it can pick up traces of ancient campfires extinguished more than a thousand years ago.

Sensys is one of a handful of technology firms making magnetometry equipment both sensitive and rugged enough to use in difficult field circumstances, but the firm’s customer base skews overwhelmingly toward detection of unexploded ordnance. The forests, fields, and city streets of Europe are still haunted from below by these bombs, a problem that is now very much global—and not necessarily limited to land. Konieczek showed me how in one of the firm’s assembly rooms, watertight magnetometers in titanium cases were being prepared for use at underwater sites, sometimes at depths approaching four miles, where they would scan shipwrecks and sunken submarines.

Konieczek pulled up a series of images to show me how magnetometry works. He clicked from an aerial photo of an empty meadow to the visual results of a magnetic scan, revealing in its black-and-white pixelated grain the clear outlines of architectural shapes hidden in the ground. Although Sensys is a global pioneer in magnetic technology, magnetometry itself has existed for nearly two centuries; the earliest known device was invented in Germany by the experimental physicist and mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss in 1832. As the technology improved over time, eventually becoming both portable and ruggedized, it was adopted for use in archaeology.

Two geophysicists—Helmut Becker and Jörg Fassbinder—are perhaps most notable for pushing this technology transfer. Employed by Germany’s State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, they famously brought magnetometry gear to map the ruins of Troy in the 1980s, discovering deep, previously unknown fortifications. Fassbinder has since used magnetometry to map the Sumerian city of Uruk, in what is now Iraq, described in the ancient Epic of Gilgamesh, and is currently experimenting with so-called SQUID magnetometry. The “superconducting quantum interference device” is so sensitive it can also be used for advanced medical imaging.

As we clicked through more magnetic survey images resembling floor plans—Greek ruins, Roman temples, medieval villas—Konieczek pointed out that the tool works better in some parts of the world than others; the ground itself can be a limiting factor in whether magnetometry is even usable. In much of Ohio, as Jarrod Burks would also later explain to me, mile-thick Ice Age glaciers once sculpted the ground, breaking entire mountain chains down to gravel and sand. As they melted, thousands of years’ worth of erosion and vegetation transformed the landscape, leading to a thick, highly fertile layer of soil. This had at least two effects. The land—mostly mud—became an ideal, infinitely malleable building material for later construction projects, such as monumental earthworks; and Ohio’s post-glacial topography became an ideal medium for magnetometry. Those deep layers of nonmagnetic gravel and sand offer an immediately obvious contrast to the magnetic soils—and archaeological remains—above.

On one image, I asked Konieczek to stop. There was a strange feature, a kind of pinwheel structure, like the petals of a rose. That’s lightning, Konieczek said, adding that this particular image had been made by Burks. By changing the magnetic charge of anything it hits, lightning, too, leaves archaeological traces. Burks later showed me several examples of this, including the path of a barbed wire fence struck years earlier: electricity had traveled the length of the wire, leaving a straight, linear magnetic feature in the soil below. In other cases, water concentrated in the compacted clay of old mounds and ditches, exactly following the geometric foundations of those structures, can steer a lightning strike, helping to reveal architectural forms in the resulting magnetic data. This idea—that lost architecture, shining with lightning, is waiting underground for someone to find it—adds an elemental surreality to the hidden worlds archaeologists are able to see with this technology.

Although the majority of Sensys customers are not archaeologists, Konieczek explained, the firm welcomes feedback from clients such as Burks. This has resulted in such refinements as improved waterproofing and larger wheels to use in rutted landscapes. Back in Ohio, I would learn, the white PVC cart we pushed, weaving around cattle for hours, had been adapted partly in response to Burks’s own feedback and shipped to him by Sensys as a gesture of support.

THREE

Eight groups of Ohio earthworks are currently under consideration for UNESCO World Heritage status. This entails a multi-year application process that will likely lead to resolution in the next several years. The earthworks were submitted for recognition in two categories, one for sites that “bear a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is living or which has disappeared” and the other for those “directly or tangibly associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance.”

The earthworks complexes encompassed by the UNESCO bid, most quite well known, include Serpent Mound and the Newark Earthworks roughly 40 miles east of Columbus. The Newark site is a truly spectacular collection of embankments, deep moats, and geometrically aligned walls, all designated, in 2006, as the “official prehistoric monument” of Ohio. But Ohio contains many thousands of other indigenous structures, and as Burks emphasized again and again, we still don’t know where all of them are. To help address this problem, Burks, as president of the Heartland Earthworks Conservancy, has been spearheading an effort to locate, survey, and purchase sites that might otherwise face destruction.

Before I left Ohio, Burks drove me an hour south of Columbus to see Snake Den, as it’s known. Snake Den is a hilltop property owned by brothers Dean and James Barr; it has been in their family for generations. Once completely obscured by a dense thicket of trees, it got its name because, according to local lore, hundreds of snakes used to hibernate there every winter, taking advantage of warm nooks and crannies inside the three earthen mounds. Every spring, the serpents would reemerge in huge numbers. At the time Burks got involved, the mounds were all but invisible beneath tree growth and shrubs; today, they are accessible for visits, so well maintained that they earned a 2020 Ohio History Connection award for preservation.

To reach the site, Burks drove us up an unpaved farm road skirting the edge of two properties to the edge of a small meadow, where we parked. An expansive, panoramic view of southern Ohio opened up to our north; above, ravens and hawks circled, squawking and calling. Although we were only about 200 feet above the surrounding plains, the glass towers of Columbus were visible in the distance, and the landscape formed a picturesque quilt of post-harvest farmland and autumn trees.

For Burks, Snake Den is a clear-cut example of how modern technology, private philanthropy, and local family ties can come together to preserve an orphaned site. Burks has had similar success at other locations, such as the Junction Earthworks Preserve in Chillicothe. “That they were not designed for defense is obvious,” Squier and Davis wrote about these works back in 1848, “and that they were devoted to religious rites is more than probable. They may have answered a double purpose, and may have been used for the celebration of games, of which we can have no definite conception.” Although the mounds themselves are now gone, indicated only by geometric shapes carefully mowed through the tall grasses, the site has become a public park thanks to the efforts of people such as Burks.

As tools like magnetometry peel back the planet’s surface, they reveal just how culturally rich and archaeologically exciting the region’s history can be. Magnetometry might seem like little more than a shiny new tool, but it holds the promise of revealing to people all over the world that thousands of years of architectural ingenuity, cultural expression, and religious belief have shaped the country’s heartland. “When people see these earthworks, they begin to understand that these were incredibly intelligent people who did amazing things,” Diane Hunter, tribal historic preservation officer for the displaced Miami tribe of Oklahoma, told me. “They weren’t ignorant, primitive people, which is how they’ve always been described. As people learn about the truth of our ancestors, they begin to understand the truth of who we are today.”

Geoff Manaugh is a Los Angeles–based architecture and technology writer. Research for this article was supported by a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.