The secret police: A private security group regularly sent Minnesota police misinformation about protestors

When US marshals shot and killed a 32-year-old Black man named Winston Boogie Smith Jr. in a parking garage in Minneapolis’s Uptown neighborhood on June 3, 2021, the city was already in a full-blown policing crisis.

Around 300 officers had quit over the previous two years amid near-constant protests and public criticism in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by a member of the police force in May 2020. Intense debates over the Minneapolis Police Department’s budget raged, and some Minneapolis council members were elected after campaigning on a platform of defunding the police. Adding yet more strain to the shorthanded department, homicides had increased almost 30% across the US in 2020. Vital services were starting to fail—in the first half of 2021, response times to 911 calls in Minneapolis increased by 36%.

Minneapolis had been at the vanguard of activism on policing and racial justice since Floyd’s death. After Smith’s killing, protests reignited all over the city—not only at public spaces, like the intersection where Floyd was murdered, but also in private ones, like the parking garage where Smith was shot. As demonstrations spread from the streets into shopping districts and parking lots, the cops couldn’t keep up.

Into the void stepped private security groups. The number of new companies applying for licenses from the Minnesota Board of Private Detective and Protective Agent Services ballooned from 14 in 2019 to 27 in 2021. Beginning in 2020, many Minneapolis property owners hired these private security organizations, ostensibly to prevent property damage. But the organizations often ended up managing protest activity—a task usually reserved for police, and one for which most private security guards are not trained.

According to documents obtained by MIT Technology Review through public records requests, there are 13 private security guards for every one police officer in downtown Minneapolis. There are currently 172 security groups and individual detectives with active licenses in Minnesota, from private investigators to companies with sophisticated surveillance operations and thousands of employees. They offer a range of services focused on the protection of property and privately owned assets. Some are heavily armed, some rely on open-source intelligence, and many have relationships with police departments.

And while the Minneapolis Police Department maintains public-facing policies for First Amendment activities like demonstrations and protests, there is no such requirement for private security groups. Similarly, police are accountable for their actions to the city government, and voters, whereas private groups are not.

The Secret Police: An MIT Technology Review investigation

This is the fifth story in a series that offers an unprecedented look at the way federal and local law enforcement employed advanced technology tools to create a total surveillance system in the streets of Minneapolis, and what it means for the future of policing. You can find the full series here.

In our look at over 400 documents, we found that during the protests after Smith was shot, several private organizations were providing security services at and around the parking garage where the killing took place, including We Push for Peace and W&W Protection. One company, Conflict Resolution Group, came up repeatedly.

The documents reveal that Conflict Resolution Group (CRG) regularly provided Minneapolis police with information about activists that was at times untrue and politicized. CRG also intimidated activists and revealed the identity of protesters; anonymous protest has been consistently upheld by the Supreme Court as a constitutionally protected activity. The Minneapolis Police Department referred the group to other businesses, despite concerns within the department about its behavior.

The city of Minneapolis, like many cities, maintains ties with many private security groups. A public-private partnership through the city’s Downtown Improvement District connects private security groups with police departments and businesses, and provides information-sharing infrastructure like radio equipment and regular meetings.

But CRG stands out for the prominent and controversial role it has played in the city’s reckoning with racism and police violence. From July through at least December 2021, the organization maintained a presence at the garage where Smith was killed, which had become a frequent protest site. The group’s tactics caused some protesters to fear for their personal safety. On its website, the group publicly touts its military-style operation, stating that it “specializes in all facets of high threat protection operations, surveillance, social media tracking and drone operations that were learned and honed on the battlefields of Iraq and Afghanistan and in high threat permissive environments in Libya and Somalia.”

The group hasn’t disclosed how its employees train for the difficult task of protecting private property while simultaneously ensuring the rights of fellow Americans—including the right to anonymity in public protest, a key tenet of the US Constitution’s free-speech protections. Minnesota state statutes do not require private security groups to undergo any training related to the First Amendment, though there are training mandates for firearms and deescalation tactics, among other things. The company’s CEO, Nathan Seabrook, told MIT Technology Review that many of our findings are false. However, CRG did not respond to multiple requests for clarification or comment.

How CRG intimidated a protestor

Seven Points is a collection of several popular shops and restaurants adjacent to the parking garage where Smith was killed. A management company for the Seven Points property—which a spokesperson declined to name—hired CRG, which was at the garage in July, to assist with security related to protests that broke out there.

Emma Ruddock, an artist and a musician, lived half a block away from the parking structure and had been outside her apartment when Smith was killed. She says she heard the fatal gunshots and watched police usher Norhan Askar, the woman Smith was with when he was shot, into a police car.

In the weeks after the shooting, activists occupied a small lot of grass next to the garage and erected a “peace garden” that memorialized Smith and Deona Marie Knajdek, an activist who was killed when a man plowed into a barricade during a protest shortly after Smith’s death. Ruddock became a frequent presence at the garden, photographing and recording the activism in her neighborhood and adding her voice to criticisms aimed squarely at law enforcement and, later, at CRG and Seabrook.

Over the course of the summer, the relationship between activists and CRG had grown increasingly tense as the group staffed the area with security guards, many of them outfitted in military gear and armed with rifles. A spokesperson for Seven Points says the company had intended to keep the peace garden open, but said in a statement to MIT Technology Review that the garden “became a nuisance, an encampment, and a gathering place for drug activity and violence.” The company noted on its Instagram page that “continued destruction of property, violent acts, arson, noise ordinance violations, and blocking access to Uptown residents and businesses created an unsustainable and unhealthy situation.” The company provided no evidence of drugs or violence on the property, despite multiple requests. In its statement, a spokesperson for Seven Points also said it served “dozens of individuals with trespass notices,” though it provided no documentation. At least one individual was arrested for trespassing on the property in July.

In the fall, Ruddock had a run-in with CRG that left her shaken. During a protest on the night of October 3, she and about 100 others gathered near the parking garage to commemorate the four-month anniversary of Smith’s passing. A metal fence, concrete barriers, floodlights, and spotlights were erected around the peace garden, relegating protesters to the public sidewalk.

As protesters chanted, acoustic guitar music began playing over CRG’s loudspeakers. Ruddock was shocked to hear her own voice begin serenading the crowd with a love song—”so please please choose your words carefully ’cause I will keep them in my sweater.” The crowd was unaware, at the time, that the music was written and performed by her. She says the song was played several times.

“I felt like I was in a nightmare. It was just so deeply incongruous,” she says. “Honestly, I felt quite humiliated by it, because there were all these people who were trying to speak and they were being drowned out.” Ruddock says, “It was so grotesque and obviously designed to make me know that they were watching me.” CRG had identified her, found a video of her music, and “blasted my music through my neighborhood.”

“I felt like I was going to have a panic attack,” she says. Ruddock tried to explain the situation to other activists—many of whom didn’t know that she was a musician, much less that it was her song—and quickly left the protest. She doesn’t know why she was singled out but suspects it was because she was frequently in attendance at the area around Seven Points with camera in hand, photographing the unrest in her neighborhood.

CRG also played recordings of speeches made by Martin Luther King Jr. to drown out chants at protests, according to three activists we spoke with. According to Rick Hodsdon, the chair of the Minnesota Board of Private Detectives and Protective Agent Services, no formal complaints against CRG have been filed. A complaint would trigger an investigation by the agency and could lead to revocation of security licenses and, potentially, criminal charges.

A look at the “intel reports”

What Ruddock couldn’t have known is that CRG also operated like a covert intelligence team for the Minneapolis Police Department. According to emails obtained by MIT Technology Review, CRG surveilled activists in Uptown and often sent reports to the department. One such 17-page report, entitled “Initial Threat Assessment,” described the organizers as part of “antifa,” a term often used in far-right discourse to exaggerate the threat posed by radical left-wing political groups. Ruddock was identified as one of the leaders of antifa, a claim she calls “ridiculous” and says she has “never been affiliated with antifa or any extremist groups.”

(MIT Technology Review is not publishing the reports we reviewed because of the risk of spreading false and potentially defamatory information.)

Some of the reports include information sourced from the internet and social media, as well as photographs of Ruddock and other activists. In one exchange between Seven Points and MPD, Seven Points referred to CRG’s “cameras they do surveillance with.” Some information is drawn from the website AntifaWatch, including mugshots of Ruddock and other activists from a mass arrest during a protest on June 5, 2021, two days after Smith’s death. The 2021 charges against Ruddock have since been dropped for “insufficient evidence,” and there is pending litigation against the city surrounding the arrest.

AntifaWatch says it “exists to document and track Antifa and the Far Left.” The site publishes photographs of almost 7,000 people allegedly engaged in antifa or antifa-associated activities, along with other information about them. Its information is sourced from news reports, social media posts, and submissions that anyone can make. The website states that “for a Report to be approved it must have a reasonable level of proof (News article, arrest picture, riot picture, self-identifying, etc).” MIT Technology Review attempted to verify several of the entries on the site and found inaccuracies. For example, the daughter of New York City’s former mayor Bill de Blasio is included on the list for an arrest at a Black Lives Matter protest on May 31, 2020, in New York City. AntifaWatch characterized Chiara de Blasio as “rioting with antifa,” though the police report does not indicate that de Blasio participated in rioting.

The website states that “a report on AntifaWatch is in no way, shape or form an accusation of one’s involvement in Antifa, terrorism, or terroristic groups” and says that it “is not a doxxing website,” though it explicitly attempts to identify and reveal personal information about people. Its posts often contain bigoted language. It also features a facial recognition feature: anyone can upload an image, and the website will return potential matches from its AntifaWatch database.

According to a domain registration search of antifawatch.net, the website is registered to Epik Holdings, a web hosting service popular with far-right websites (including Parler and Gab) that have been denied hosting by other internet service providers. AntifaWatch declined to comment for this story.

Ruddock says she had trouble getting a job after her information was uploaded to AntifaWatch, which now is the top result in a Google search for her name and Minneapolis. Her lawyer requested in an email that AntifaWatch remove her information but received no reply.

“Over the last several years, the ‘antifa’ label has become a political cudgel wielded by conservative politicians and activists who engage in threat-mongering about the far left,” says Michael Kenney, a professor of international affairs at the University of Pittsburgh who studies antifascism and political violence. “These conservative activists and politicians seek to rally like-minded supporters by demonizing far-left activists and exaggerating the threat they pose to American society.” Kenney says the idea that antifa operates as some kind of shadow group pulling strings behind the scenes at protests is far-fetched. Only a few thousand people belong to radical antifascist political groups in the US, he says, and many will openly disclose their political views.

MIT Technology Review has not found evidence that Ruddock is a part of a radical antifascist political group. Minneapolis Police have not replied to our requests about antifascist activity in Uptown. In one email from September 2021 found in public documents, police do mention “local antifa/anarchists” in Minneapolis, though an investigation by the FBI in December 2020 found no evidence of “antifa-led riots” during the protests and unrest after George Floyd’s murder. Michael Paul, special agent in charge of the FBI’s Minneapolis Field Office, said at the time, “We haven’t seen any trend of antifa folks who were involved here in the criminal activity or violence.”

Along with its accusations that Ruddock and others are members of antifa, the CRG report entitled “Initial Threat Assessment” contains a grab bag of questionable information about the threat of antifa extremist groups in the Minneapolis area. The report cites right-wing content creator Andy Ngo as a source and even questions the science of climate change.

The report also includes screenshots from Ruddock’s private Instagram account. That report and others show that CRG surveilled several other activists in addition to her, though she is mentioned more than anyone else.

Partnering with police

It doesn’t appear that CRG and the Minneapolis Police Department have a contract, but the two have a complex working relationship.

Emails we reviewed from public records requests show that CRG sent at least eight reports to the Minneapolis Police Department from March to December 2021 about activities related to the area around Seven Points, as well as other properties its guards were patrolling. The group also sent over different versions of its reports to MPD, including a shorter “flash” report, which appears to include more real-time information about activity around Uptown, including surveillance footage of the garage. The reports often contained unreliable or unsubstantiated information.

For example, the group sent MPD an “individual of interest” report that includes information sourced from Twitter about someone with a tattoo commemorating the burning of the MPD Third Precinct during the 2020 protests. CRG insinuated that the tattoo shows this person might have been involved in the crime and reported that the person has “possible gender dysphoria.” “Our findings are based off of our analytical experience working in conflict zones, tracking various terror groups and providing analytical insight and perspective during the global war on terror,” the report says, before adding: “Our team reached out to contacts in our intelligence network and asked two other government affiliated analyst [sic] to look at the picture and the tattoo and give an analytical perspective.” According to Minnesota court records, this person has never been tried for any crimes.

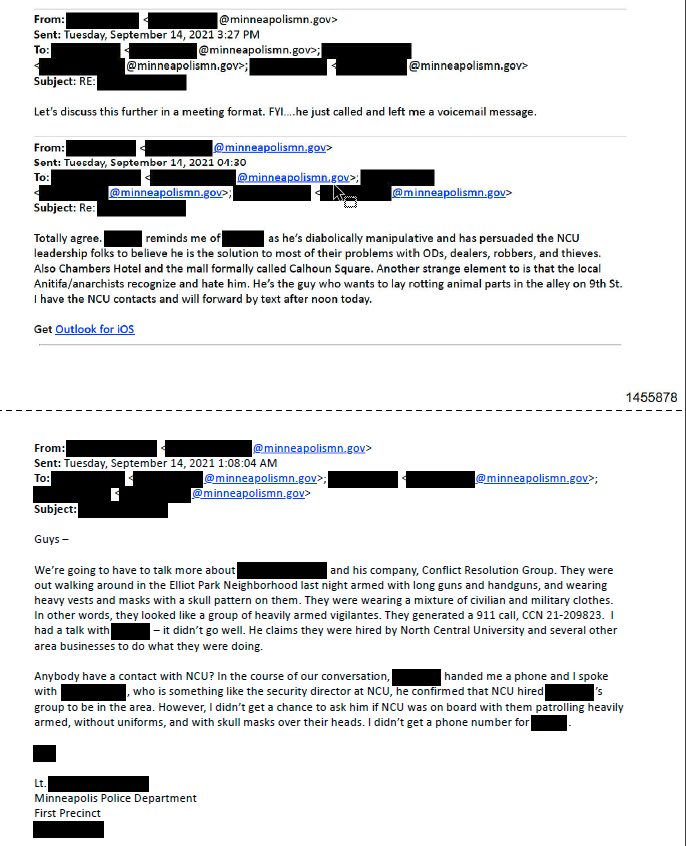

Officers in the Minneapolis Police Department appeared to have reservations about CRG and its CEO, Seabrook. On September 14, 2021, one officer sent an internal email saying the department had “to talk more about Nathan Seabrook and his company, Conflict Resolution Group,” which the officer said “looked like a group of heavily armed vigilantes.” Another officer called him “diabolically manipulative” and said, “He’s the guy who wants to lay rotting animal parts in the alley on 9th St.,” apparently in order to deter people from lingering in a supposedly drug-ridden space.

Despite such hesitation, the emails reveal that the MPD facilitated connections between CRG and groups dealing with persistent security issues such as drug use and violence on private property. In an exchange on August 17 between a Minneapolis Police Department officer and the head of operations at North Central University, which is located in the city, the North Central University employee says that the university’s president required a referral from MPD to use CRG, and an inspector on the force provided one. In another exchange, an MPD officer connected two local businesses that had contracted with CRG to the Downtown Improvement District.

MPD told MIT Technology Review in an emailed statement that the department “interacts daily with private security personnel throughout the city,” adding: “MPD does meet with security personnel to discuss expectations, civil vs criminal issues, private vs public issues, and emphasize the importance of employing de-escalation.” The statement goes on to say that “examples of MPD’s continued interaction with private security companies and personnel include the US Bank Stadium, Target Center, and all area hospitals.” MPD did not reply to our questions about the department’s specific relationship with CRG or the level of criminal activity in Uptown.

“I was very scared”

Beyond the area around Seven Points, private security guards are managing protest activity all over Minneapolis. These groups are far less regulated than police departments. In the case of CRG, which seems to rely heavily on monitoring social media and questionable websites, it’s had a chilling effect on people’s willingness to exercise their right to freedom of speech.

We spoke with a number of activists involved in the Uptown protests who found CRG’s methods excessive. “They want to scare you by shouting facts anyone can find in your social media bio, and they’ll go a step further by waiting until you’re alone before making comments that show they’re actively monitoring social media posts,” explained Aisha Kaylor, who was identified by CRG as a protest leader in one report sent to Minneapolis police. Kaylor says she took part in what she called vigils and community gatherings largely by bringing water and snacks. She is concerned about the “open, back-and-forth communication of information gathered by CRG’s ability to do essentially whatever they want, including actively and closely monitoring social media.”

And while she admits that she “laughed out loud” when she saw the photo and the description of herself as a “leader” from CRG’s report, Kaylor is still worried by the whole affair: “It’s irrational to not be worried about what their ability to gather intelligence and so easily share it with MPD means.”

Ruddock, the musician, says she watched her neighborhood transform into something unrecognizable. She says CRG wasn’t alone in contributing to the atmosphere of intimidation—other groups on the premises, including We Push for Peace and W&W Protection, treated activists similarly. By winter, protests in Uptown had dissipated and she was going to the area around Seven Points less frequently, in part out of fear for her personal safety.

CRG has not responded to questions about its tactics, relationship with police, and activity at the area around Seven Points property. We Push for Peace and W&W Protection also did not reply to our inquiries.

We first spoke with Ruddock in the fall of 2021, and she was still living in the neighborhood around Seven Points. She had stopped using her name with people she met unless absolutely necessary. She’d drive her car around the block before parking at night so as not to be seen or followed home, and she would bring her bike inside wherever she went to conceal her location from anyone outside. “I was very scared, and I’ve continued to feel very scared,” she says. “I’ve developed habits to avoid feeling like—I don’t know—that they can see me.”

We reviewed our findings with Rick Hodsdon, the chair of the Minnesota Private Detective and Security Board. When asked about CRG’s practice of monitoring activists and filing reports on them to police, he said he didn’t believe there was anything “in the law that prohibits that behavior.” He noted that private citizens and groups often send tips to police.

Hodsdon acknowledged that demand for private security is growing rapidly, mainly from property owners and other private citizens. “Police are not relying more on private-sector security,” he said. “The members of society are, and the members of society are relying more on private-sector security because of the shortages [and because] of not being able to rely on having a public-sector police officer available when you need them.”

Indeed, there is a long history of private security groups acting in lieu of law enforcement, and engaging in questionable legal activity while doing so. In 2017, the oil company Energy Transfer Partners hired the private security group TigerSwan to suppress protests at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation against the Dakota Access Pipeline.

TigerSwan compared activists to “jihadists” in shoddy intel reports and touted its experience in armed conflict zones, much as CRG does. Jamil Dakwar, the director of the ACLU Human Rights Program, said at the time, “The First Amendment’s guarantee of the ‘right of the people peaceably to assemble’ cannot be reconciled with private military contractors deploying against peaceful protesters on domestic soil with little or no oversight or accountability. Their collaboration with federal, state, and local governments requires a credible and independent investigation.”

In other words, security groups “are not there to protect anybody’s First Amendment rights, right?” as Hodsdon put it. “They’re there to protect the safety of consumer staff and physical property of whoever hires them.”

Jess Aloe contributed additional reporting.