Inside the fierce, messy fight over “healthy” sugar tech

In a former insurance office building on the outskirts of Charlottesville, Virginia, a new kind of sugar factory is taking shape. The 48,000-square-foot facility is being developed by a startup called Bonumose, funded in part by Hershey. It uses a processed corn product called maltodextrin that is found in many junk foods. Like its notorious counterpart high-fructose corn syrup, maltodextrin is calorically similar to table sugar (sucrose), is just as bad for your teeth, and actually causes worse blood sugar spikes.

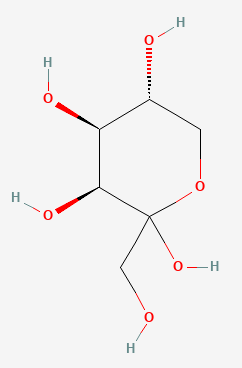

But for Bonumose, maltodextrin isn’t an ingredient—it’s a raw material. When it’s poured into the company’s gleaming bioreactors later this year, what emerges will be a “rare sugar” called tagatose. Found naturally in small concentrations in fruit, some grains, and milk, it is nearly as sweet as sucrose but with only around half the calories. And because of the way it is metabolized, tagatose can actually improve dental and digestive health, and even stabilize insulin levels.

Although long recognized as a safe food ingredient by the FDA, tagatose has proved expensive and difficult to isolate—until now. Hershey says that Bonumose’s technology, designed to affordably convert maltodextrin into tagatose at commercial scales, is critical to its effort to formulate next-generation “better-for-you” candies.

“If we can sell anywhere near the volume of high-fructose corn syrup, then you’re talking tens of billions of dollars a year [in] revenue,” says Ed Rogers, Bonumose’s CEO. “And the effect on public health could save arguably trillions in health-care costs.”

Bonumose’s multi-enzyme conversion process originated in a company spun out of the Virginia Tech lab of Yi-Heng “Percival” Zhang. Born in China, Zhang is a bioengineer with a string of awards and inventions to his name. In 2006, Esquire magazine singled him out as one of America’s “best and brightest” for his work on converting sugar from farm waste into cheap ethanol. His lab spun out companies to build a sugar-powered “battery” for smartphones, produce medicinally useful compounds, and explore using sugar to generate hydrogen for fuel-cell vehicles. “Sugar will be the new oil,” Zhang’s email signature at Virginia Tech once pronounced.

But Zhang today isn’t sitting proudly at the helm of Bonumose’s research division, or formulating healthy chocolate, or racing a sugar-powered car. When MIT Technology Review spoke to him in January, he was sitting alone in an empty lab in Tianjin, China, after serving a two-year sentence of supervised release in Virginia for conspiracy to defraud the US government, making false statements, and obstruction of justice. He still seems dazed from his dealings with Rogers—his former business partner—and the US government. If you ask Zhang, he was guilty of nothing worse than poor judgment and ignorance of the rules; he sees himself as a man brought low by treachery. “They cheated the technology from me. They robbed me and took everything,” he says.

Turn an ear to Bonumose, however, and it’s about the triumph of American entrepreneurship over the Communist government of China. “We did not cheat anyone,” Rogers told MIT Technology Review. “Even though we had this pretty bitter battle with Zhang, we don’t wish him any ill will at this point. Maybe he wants to blame someone other than himself, but he should look in the mirror.”

Whichever version hews closest to the truth, one thing seems clear. If sugar is the new oil, the global battle to control it has already begun.

Most humans love sugar for its gloriously sweet taste and ability to give blood sugar a turbo-boost, but Zhang is more interested in the energy it packs. His parents were physicists in Wuhan, China, and Zhang grew up eager to emulate scientific heroes like Edison, Curie, and Pasteur. After studying biochemical engineering in Shanghai, he came to the US in 1997 for a PhD at Dartmouth College, where he also met his wife.

His first enthusiasm was for biofuels, a growing research topic in the early 2000s. At Dartmouth, Zhang validated a process for accelerating the conversion of agricultural waste like corn leaves and rice straw into sugars, and thence into ethanol for fuel—the “sugar-powered car” that got Esquire so excited.

In 2005, Zhang joined Virginia Tech as a tenure-track professor in the biological systems engineering department. One of his first graduate students was Joe Rollin, an idealistic young chemical engineer straight out of the US Army. “I was looking to combine my background with helping to mitigate geopolitical conflict,” Rollin says. “Biofuels was the obvious direction. And from my very first meeting with Percival, entrepreneurship came up.”

To support MIT Technology Review’s journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

In 2010, Zhang, Rollin, and another graduate student, Xiao-Zhou Zhang (no relation), founded Gate Fuels to commercialize their discoveries. A second spinout, Cell-Free Bioinnovations (CFB), followed in 2012. Zhang was the companies’ president, and Rollin their CEO.

The companies relied heavily on grants from the National Science Foundation. Two early awards were for a strain of soil bacteria engineered to produce precursors to plastics and fuels. Others went to the development of sugar-powered enzymatic fuel cells, a “bio-battery” with an energy density potentially 20 times that of lithium-ion batteries. Instead of plugging in their smartphones to recharge, future users might be able to top them up with sugary Coca-Cola.

“My vision was that we would prove out the technologies, then license them to industrial partners to scale up,” Rollin says. “Percival was okay with that strategy, but his interest was always in changing the world. I think he was very frustrated with how slow things seemed to be.”

In late November 2014, Zhang—by now a naturalized US citizen—could wait no longer. He wrote an open letter to President Obama, the secretaries of energy and agriculture, and Congress, warning that the US risked missing out on the coming “megatrend” of next-generation biomanufacturing, renewable energy, and sustainable agriculture. He asked them to organize a special consortium of research institutes and industrial companies. “Keep it in mind,” he wrote, “China is the largest industrial biotechnology nation. If the USA failed to take action now, the USA might [lose] this important game forever.”

He never heard back.

Shortly after, Zhang left on a three-week trip to China. He was starting a part-time contract at the Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology (TIB), a research institute of the national Chinese Academy of Sciences. “They were working on some projects that were very interesting,” Zhang says. “They said, ‘We know you have a lot of good projects. Why don’t you start a lab? You can hire several people and work on projects that you’re not doing in the US.’ For academics, this is common and a good idea.”

Zhang did not hide his involvement with TIB. He paid US taxes on his Chinese income (about $30,000 a year) and diligently notified Virginia Tech of his work abroad, which he says was never questioned.

Zhang’s second spinoff, CFB, meanwhile, appeared to be doing well. Zhiguang Zhu, one of Zhang’s Chinese graduate students and chief technology officer of CFB, was applying for more NSF grants. The company applied for one for improved production of a sugar called inositol. Inositol is used in supplements, to treat some mental-health issues, and as a harmless stand-in for cocaine in film and TV. The team won an award for research into the cheap production of sugar phosphates—components in the manufacture of drugs used to treat cardiac diseases, cancers and degenerative diseases. And NSF green-lighted a $750,000 proposal—CFB’s largest NSF award—to continue work on sugar-powered enzymatic bio-batteries.

Around this time, Joe Rollin secured a position at the Department of Energy’s ARPA-E research agency. To replace him, he recommended Ed Rogers, an entrepreneurial businessman with a background as a lawyer. Rogers had cofounded a company in 2003 to make edible (rather than plastic) fishing lures. He later ran a clean-energy research center in southern Virginia, using grants from tobacco settlements to promote biofuels, LED lighting, and energy efficiency. “Ed brought startup commercialization and legal experience to the team, and hit things off well with Percival,” says Rollin. “To me he was an easy hire.”

In January 2015, Zhang signed Rogers on a one-year contract as interim CEO. His duties would include performing a due diligence checkup on the company’s governance, policies, and intellectual property. But his primary goal would be raising public and private funding for CFB, which needed a steady stream of income to keep up with the pace of Zhang’s imagination.

By then Zhang’s enthusiasm had turned to tagatose, which interested him as a potential sugar replacement. “We need a better low-calorie sugar,” he later explained. “Tagatose is one of the best. The reason is the taste, which is very close to sucrose, and it’s also very good as a prebiotic, supporting beneficial bacteria in the body.” A new CFB employee, Daniel Wichelecki, contributed some interesting ideas about a high-yield, multi-enzyme conversion process for tagatose, which can be produced today in only modest amounts in a mixture that is expensive to purify. CFB filed a provisional patent application on the new process, citing Wichelecki as inventor and Zhang as co-inventor.

Rogers hit the ground running. By the end of 2015, he claimed to Zhang to have contacted dozens of potential licensees for CFB’s rare sugars. He said he had developed working relationships with several, and had “good bidders lined up.”

Sure enough, when British food giant Tate & Lyle expressed an interest in inositol after attending a lab-scale production demonstration, Rogers was keen to move forward. But Zhang refused, eventually saying that CFB controlled less intellectual property than Rogers had thought.

In an email to Rogers that December—obtained, like most of the others in this story, from court filings—Zhang wrote: “Some projects that you thought were owned by CFB are not owned by CFB.” He explained that both the inositol and the sugar phosphate technologies actually originated in his TIB lab and had been funded by a Chinese agency before CFB began work on them. This would mean, he wrote, that CFB could not claim full ownership of either, but only build upon the Chinese work.

Before that e-mail, Rogers had proposed splitting CFB, leaving Zhang his sci-fi bio-battery and sugar-to-hydrogen concepts, while Rogers would commercialize the nearer-term rare sugars. Zhang dismissed the idea, and to no one’s surprise, he did not renew Rogers’s CEO contract, later citing his “failure to raise a single investment dollar.” But Rogers, who retained a small stake in the company as part of his compensation, was not ready to walk away. At the end of December 2015, he sent CFB an email referencing a “glaring” contradiction between statements the company had made in NSF grant applications while he was interim CEO and statements made by Zhang.

As an example, Rogers pointed out that while Zhang had told him the rights to the production process for sugar phosphates were Chinese, one application stated that CFB owned the rights and would commercialize the process in the US. “If there is a problem,” Rogers warned, “I cannot look the other way. Of course, any whiff of grant fraud will cause potential licensees and potential investors to flee.”

In the email, Rogers reiterated his suggestion that CFB transfer the rights for tagatose and another rare sugar called arabinose, as well as the rights for the sugar phosphates process, to a new startup he was intending to form. But he wanted to move fast, ideally within a week. “If you need more time, please let me know, but time is running short in several ways,” he wrote.

Zhang again refused to split the company, and on January 6, 2016, time ran out. Rogers incorporated Bonumose in the state of Virginia and, nine days later, sent an email to the NSF’s Office of Inspector General entitled “Report of possible NSF grant fraud.”

It quoted from some seemingly damning emails between Zhang and Rogers. In one, sent in the summer of 2015, Zhang writes: “About sugar phosphate project, the experiments have been conducted by one of my collaborators and my satellite lab in China. The technology transfer will occur in China only. If this project is funded by [the NSF], most of money will be used to fund the other project in CFB.” That meant the promising tagatose research, which had not yet received any official NSF funding.

Another, regarding a second NSF inositol proposal, took a similar tack: “Nearly all experiments … have been finished. Chun You [CFB’s chief scientist] and I have filed a Chinese patent on behalf of ourselves, no relation to CFB … If it is funded, most of [the NSF money] will be used for CFB to support the other projects.”

Using government funds for a different purpose from the one for which they were awarded is strictly, and explicitly, forbidden. Within weeks, the NSF had begun its investigation and suspended all payments to CFB.

Inside the company, chaos reigned. Zhang had previously asked Dan Wichelecki and his partner, a lab manager at CFB, whether they would consider moving to China to work with him, but neither was keen. Joe Rollin, who was still on CFB’s board but no longer involved in day-to-day operations, remembers having mixed feelings about the situation: “On one hand, Ed had concerning claims about grant mismanagement by Percival. But on the other, Ed stood to profit from getting Percival out of his way. I didn’t really know who to trust.”

In a letter to Zhang in early February 2016, Rogers pleaded with him to step aside. “You helped start what might be able to become a successful company,” he wrote. “Please do not stubbornly stand in the way of that potential for success. Your resignation would start to fix the problems you created.”

While Zhu was ready to side with Zhang, Wichelecki was conflicted. “Ed is primarily motivated by personal compensation … but this is business so no big surprise there. We are all here for money,” he wrote to Zhu in February 2016. “I really just want to try and commercialize tagatose, but I do not see how this is going to be possible.”

Rogers did. He again proposed that Bonumose take CFB’s tagatose IP, and he offered to sweeten the deal by hiring Wichelecki, whom CFB could no longer afford to pay, as a cofounder. In return, CFB would receive a one-third ownership stake in Bonumose and a few modest payments from the new company. CFB and Zhang would also have to promise to stop work on tagatose and sugar phosphates.

Zhang felt he had no choice but to agree, and in April 2016 he signed an asset sale agreement that would transfer the tagatose IP to Bonumose and require Rogers to help resolve the NSF investigation. In a court filing, Zhang later claimed: “Rogers used the crises he had created for CFB and Zhang to force CFB and Zhang to execute the April 2016 agreement.”

With CFB now effectively shut down, Zhang moved the company into his basement at home, and turned his thoughts to China. In June 2016, he applied to China’s Hundred Talents Program, an effort to boost the country’s scientific expertise by recruiting foreign and expatriate Chinese researchers to Chinese institutions with generous financial, infrastructure, and research packages.

Zhang’s application, seized as part of the NSF case and translated by the FBI, details his plans to transfer “three to four major results” within five years. Despite his promise to Bonumose and commitments to CFB, these would include producing tagatose and a sugar bio-battery, and integrating “various technologies” to produce the first car in the world running on hydrogen from sugar. Zhang told MIT Technology Review that the underlying science in this proposal was different from that of Bonumose and CFB.

Zhang’s application notes that his 15-strong research group at TIB would join two other research groups there, run by former CFB employees Zhiguang Zhu and Chun You. Both would return to China during 2016 or 2017.

“[I aim] to accumulate enough dividend from technology monopoly, stock dividend, and option income to build the first Bell Lab–style research and development base in China,” stated his Hundred Talents pitch, before requesting visas, work permits, and health insurance for his family. He asked, too, for a nicer office and additional lab space for himself. Zhang says he also applied for jobs at Cornell University and the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology.

That summer, Zhang embarked on a seven-week trip to China, during which he received a subpoena from the NSF for time sheets relating to CFB’s awards. He forwarded the request to Zhu, who was principal investigator on the projects. In the chaos of the office move, Zhang says, neither he nor Zhu had any idea where the time sheets might be, so they re-created them to the best of their recollection and submitted what he calls “make-up” sheets to the NSF.

In January 2017, Zhang visited China again. His itinerary—another exhibit in the US government’s case against him—shows a packed fortnight at TIB. Zhang received a fee of 10 million yuan ($1.6 million) for transferring inositol technology into the private sector, and he planned the next phase in that project. He discussed his lab’s detailed plans for working on tagatose production and a sugar battery. The icing on Zhang’s cake was receiving Binhai New District’s “Top-Caliber Innovative and Entrepreneurial Professionals Award.”

There were no awards awaiting Zhang on his return. In fact, he was soon facing a civil lawsuit from Bonumose that accused Zhang, You, CFB, and TIB of stealing confidential information and trade secrets relating to tagatose. Ed Rogers had been alerted to a Chinese patent that was, in the words of the lawsuit, “nearly identical to” the provisional patent application that Zhang and Wichelecki had filed back in 2015 and that was now owned by Bonumose. The Chinese patent listed four inventors: two TIB researchers and two individuals who asked to remain anonymous. Rogers was convinced those two people were Zhang and You—an accusation that Zhang denied.

Zhang was accepted into the Hundred Talents program in mid-2017, whereupon he resigned from Virginia Tech.

With the civil case brewing, the government finally sprang into action. On September 20, 2017, agents executed a search warrant at Zhang’s home in Blacksburg. In a basement cabinet, they found three binders of time sheets in a format different from those previously sent to the NSF. They also found a canceled Chinese passport in Zhang’s name.

A conversation in Mandarin with Zhang’s mother, who was visiting at the time, suggested to the FBI that he might flee to China. Together, it was enough for Zhang to be considered a flight risk. He was arrested and jailed in nearby Roanoke. Zhang remained locked up for over three months. While his experience there was “terrible,” he says, he also underwent a religious awakening. By the time Zhang was finally released after Christmas, he started going by a new name: that of the long-suffering prophet Job.

But his travails were far from over. In the run-up to a bench trial in September 2018, Rogers repeatedly reached out to law enforcement, ultimately providing a spreadsheet listing additional violations he attributed to Zhang, including transporting stolen goods, failing to register as a foreign agent, and committing wire fraud. In his defense, Zhang called an expert witness who testified that the experiments previously carried out by his group at TIB were different from those in CFB’s NSF proposals. If they were different, and the NSF had been funding new experiments, that would likely not have been a crime. The judge, however, concluded that “Zhang’s statements in his emails establish the innate falsity of the inositol proposal beyond a reasonable doubt.”

Zhang was found guilty of conspiracy to defraud the United States, making false statements (the made-up time sheets), and obstruction. His co-defendant, Zhu, had long since returned to China and was now considered a federal fugitive.

“The prosecutor lied again and again,” Zhang told MIT Technology Review. “It’s true that I had two passports, but my Chinese passport was invalid.” He also disputes the government’s interpretation of his conversation with his mother: “They translated my words in Chinese a different way. Then in court, the translator said she couldn’t remember.”

Early in 2019, Bonumose settled its civil suit. The terms were confidential, but both Zhang and Rogers confirmed that Zhang no longer has any ownership stake in Bonumose. Although TIB paid most of Zhang’s legal fees for the civil case, Zhang says the criminal case cost him approximately $800,000, draining his savings and IRA accounts, and leaving him deeply in debt to friends and family.

In September 2019, after a year spent under house arrest, Zhang finally faced his sentence. The US government called for a $100,000 fine and five years of incarceration. Instead, the judge ordered him to pay just $500 and serve two years of supervised release, during which Zhang would have to stay in western Virginia. “His life is effectively ruined,” said the judge, according to a local news report, noting that Zhang hadn’t profited personally, had lost his career and reputation, and was unlikely to reoffend. The only monetary loss the government could suggest it suffered was the time the NSF spent processing CFB’s grant applications, and the agency was not able to put a dollar amount on that.

“There was no money abuse, just emails,” says Zhang, referring to the fact that he never followed through on his suggestion to use the NSF money for unauthorized projects.

“[Zhang] definitely bent rules from time to time, and he appears to have eventually gone way over the line,” says Joe Rollin. “But as far as what he was actually charged for, I don’t think justice was equally administered.”

Zhang would spend the next two years quietly at home, caring for a daughter with a brain injury and working remotely, part time, for TIB. On November 25 last year, his sentence served and his US passport restored, Zhang flew, alone, to Tianjin.

This time, there were no payouts or ceremonies. He didn’t even have a research team to greet him. “Before, I had people, but most of them left to work at other labs,” he says. “And I didn’t get the promised funding from TIB. They say, oh, that was a long time ago. We need to see if your research still works.”

The candy industry would like to know the same thing about rare sugars in general. Yong-Su Jin is a professor of food microbiology at the University of Illinois who has developed his own tagatose production system, using engineered yeast. He notes that Bonumose’s process should produce high yields of tagatose, but it requires a complex and potentially expensive cocktail of enzymes. “I think those multiple reactions can be easily implemented in a small system, but I’m not sure how robust the system will be at a large scale,” he says.

“Bonumose’s process already is proven at large scale,” Rogers said in reply. “There are no structural impediments to scaling low-cost tagatose production for the global mass market.”

The US FDA and Health Canada have both approved Bonumose’s tagatose production process, although some challenges remain. Bonumose would like the FDA to treat tagatose the way it does a similar rare sugar, allulose, which does not need to be listed as an added sugar or count toward total sugars on nutrition labels.

There are also concerns over tagatose’s effects when eaten to excess. In a filing with the FDA, Bonumose noted a year-long study by researchers at the University of Maryland involving eight people in which two withdrew after suffering diarrhea, flatulence, and bloating. The remaining subjects suffered mild gastrointestinal issues, which resolved “in all but one subject who experienced flatulence for 6 months.” Nor does everyone think tagatose is as low in calories as the FDA does. The EU reckons that each gram of tagatose has 60% more calories than the US estimate, which might make it less attractive to dieters.

Nevertheless, Big Sugar is exploring the possibilities of the new sugar technology. ASR Group, the world’s largest cane sugar refiner and marketer, invested in Bonumose alongside Hershey. ASR will be the company’s exclusive distribution partner for tagatose in North America and Western Europe.

“If we sell half a million tons of year of tagatose, that would be one-quarter of 1% of the annual sugar volume sold globally,” says Rogers. “But it would make Bonumose a billion-dollar-a-year company.”

Bonumose’s difficulties with China did not end with the civil case. In 2019, TIB challenged Bonumose’s own tagatose patent in China, dragging out the cost and uncertainty for two more years as TIB lost and then appealed that decision. “The Chinese-government-owned university spent over a million dollars in legal fees trying to kill us as a young company,” says Rogers. “We thought we could focus on growing the technology instead of having to fight this battle against the Communist Chinese government.”

Evidence gathered by the FBI also revealed that Zhang and You were indeed the unnamed co-inventors on TIB’s tagatose patent. Rogers says the validity of Bonumose’s patent has finally been firmly established, with Dan Wichelecki now described as its sole inventor.

“It was a shame the way things happened with the grant issues, because [Zhang] was a brilliant scientist,” Rogers says. “I believe in forgiveness, and I’ve forgiven him.”

The NSF certainly thinks it landed a big fish. Zhang’s case featured prominently in testimony by Allison Lerner, the NSF’s inspector general, before a House committee in October on the subject of balancing open research and national security.

Although membership in a foreign government’s talent recruitment program like China’s Hundred Talents is not illegal, the NSF wants to know about researchers’ membership in such programs because it believes that some elicit unethical and “possibly criminal” behaviors. Zhang’s was the only criminal case detailed in her testimony.

“China’s … plans are targeting the best and brightest scientists engaged in research in disciplines that are of intense interest to it all across the world,” her written testimony stated, shortly before it detailed Zhang’s case, under the headline “Grant Fraud Involving Foreign Talent Plan Participant.”

Lerner made it a point to say that race and ethnicity are not relevant in NSF investigations. Race isn’t the issue for China, she said: “knowledge and expertise in key areas such as quantum computing is. And race does not matter to us. In deciding whether we have a basis to open a case, we focus on a researcher’s conduct: was he a member of a talent plan at the time he submitted a proposal for NSF funding? Did she disclose that membership as part of the proposal process?”

However, Zhang joined China’s Hundred Talents Program only after committing the grant offenses he was later convicted of, and after the NSF had suspended payments to CFB. In reality, Zhang’s participation in the program seems to have been the result, not the cause, of the NSF investigation.

Zhang believes this misframing of his actions was deliberate, and racially motivated. “This was a political prosecution because of the conflict between China and the US … because of my race,” he says. “No matter what I do for the US, they always think I am a potential spy.”

His experience prefigured those of other researchers. The same year that Zhang was convicted, the Department of Justice launched the China Initiative, with the intention of countering economic espionage and national security threats from China. MIT Technology Review’s reporting found that the program, which targeted a number of researchers and academics, disproportionately affected people of Chinese heritage, who made up 88% of individuals charged. In February, assistant attorney general Matthew Olsen announced that the Justice Department would be ending the initiative, saying, “We helped give rise to a harmful perception that the department applies a lower standard to investigate and prosecute criminal conduct related to [China].”

Zhang, who is still a US citizen, has continued to write papers on enzymes, bioengineering, and rare sugars, some in collaboration with Chun You and Zhiguang Zhu, both of whom run thriving labs at TIB. He has no immediate plans to return to the US.

“Maybe in the future, when I’m retired, I might go back,” he says. “But working? I don’t know. Doing research is the most dangerous job in the US … My American dream was broken.”