Subtotal: 81,80€ (incl. VAT)

Deception, exploited workers, and cash handouts: How Worldcoin recruited its first half a million test users

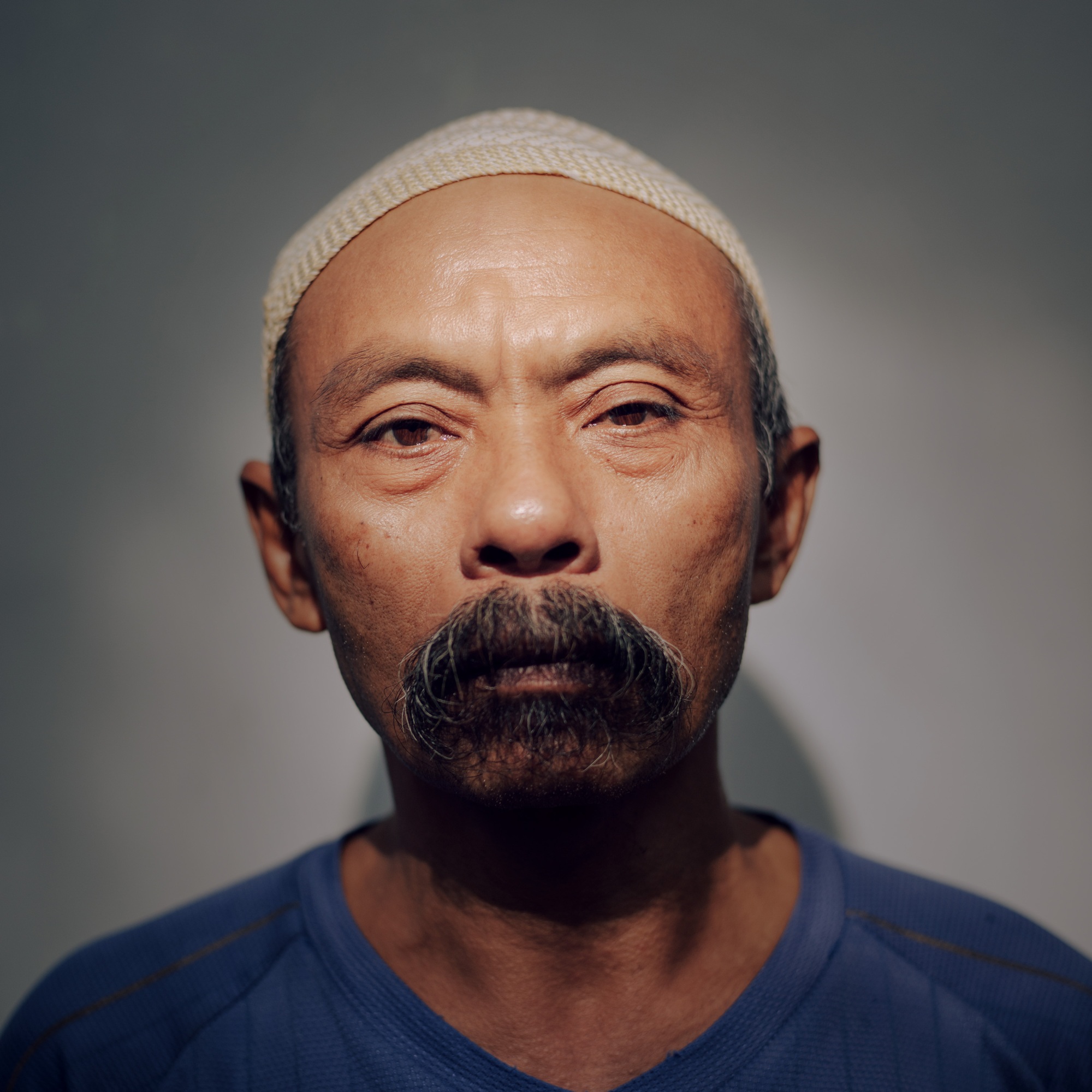

On a sunny morning last December, Iyus Ruswandi, a 35-year-old furniture maker in the village of Gunungguruh, Indonesia, was woken up early by his mother. A technology company was holding some kind of “social assistance giveaway” at the local Islamic elementary school, she said, and she urged him to go.

Ruswandi joined a long line of residents, mostly women, some of whom had been waiting since 6 a.m. In the pandemic-battered economy, any kind of assistance was welcome.

At the front of the line, representatives of Worldcoin Indonesia were collecting emails and phone numbers, or aiming a futuristic metal orb at villagers’ faces to scan their irises and other biometric data. Village officials were also on site, passing out numbered tickets to the waiting residents to help keep order.

Ruswandi asked a Worldcoin representative what charity this was but learned nothing new: as his mother said, they were giving away money.

Gunungguruh was not alone in receiving a visit from Worldcoin. In villages across West Java, Indonesia—as well as college campuses, metro stops, markets, and urban centers in two dozen countries, most of them in the developing world—Worldcoin representatives were showing up for a day or two and collecting biometric data. In return they were known to offer everything from free cash (often local currency as well as Worldcoin tokens) to Airpods to promises of future wealth. In some cases they also made payments to local government officials. What they were not providing was much information on their real intentions.

This left many, including Ruswandi, perplexed: What was Worldcoin doing with all these iris scans?

To answer that question, and better understand Worldcoin’s registration and distribution process, MIT Technology Review interviewed over 35 individuals in six countries—Indonesia, Kenya, Sudan, Ghana, Chile, and Norway—who either worked for or on behalf of Worldcoin, had been scanned, or were unsuccessfully recruited to participate. We observed scans at a registration event in Indonesia, read conversations on social media and in mobile chat groups, and consulted reviews of Worldcoin’s wallet in the Google Play and Apple stores. We interviewed Worldcoin CEO Alex Blania, and submitted to the company a detailed list of reporting findings and questions for comment.

Our investigation revealed wide gaps between Worldcoin’s public messaging, which focused on protecting privacy, and what users experienced. We found that the company’s representatives used deceptive marketing practices, collected more personal data than it acknowledged, and failed to obtain meaningful informed consent. These practices may violate the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR)—a likelihood that the company’s own data consent policy acknowledged and asked users to accept—as well as local laws.

To support MIT Technology Review’s journalism, please consider becoming a subscriber.

In a video interview conducted in early March from Erlangen, Germany, where the company manufactures its orbs, Blania acknowledged that there was some “friction,” which he attributed to the fact that the company was still in its startup phase.

“I’m not sure if you’re aware of this,” he said, “but you looked at the testing operation of a Series A company. It’s a few people trying to make something work. It’s not like an Uber, with like hundreds of people that did this many, many times.”

Proof of personhood

Two months before Worldcoin appeared in Ruswandi’s village, the San Francisco–based company called Tools for Humanity emerged from stealth mode. Worldcoin was its product.

The company’s website described Worldcoin as an Ethereum-based “new, collectively owned global currency that will be distributed fairly to as many people as possible.” Everyone in the world would get a free share, the company suggested—if they agreed to an iris scan with a specially designed device that resembles a decapitated robot head, which the company refers to as the “chrome orb.”

The orb was necessary, the website continued, because of Worldcoin’s commitment to fairness: each person should get his or her allotted share of the digital currency—and no more. To ensure there was no double-dipping, the chrome orb would scan participants’ irises and several other biometric data points and then, using a proprietary algorithm that the company was still developing, cryptographically confirm that they were human and unique in Worldcoin’s database.

“I’ve been very interested in things like universal basic income and what’s going to happen to global wealth redistribution,” Sam Altman, Worldcoin’s cofounder and the former President of Silicon Valley accelerator Y Combinator, told Bloomberg, which first reported on the company last summer. Worldcoin was intended, he explained, to answer the question “Is there a way we can use technology to do that at a global scale?”

The company was just getting started—its aim is to garner a billion sign-ups by 2023.

In the same article the then 27-year-old Blania, who joined Worldcoin straight out of a physics masters program at Caltech, added that “many people around the world don’t have access to financial systems yet. Crypto has the opportunity to get us there.” (Blania and others have used “Worldcoin” to refer to the company as well as the currency; we do the same here.)

But beyond these do-gooder intentions, Worldcoin would also solve key technical problems for Web3, the much-hyped, blockchain-powered third iteration of the internet, where data and content could be decentralized and controlled by individuals and groups rather than a handful of tech companies.

Giving “ownership in this new protocol to everyone” would be the “fastest” and “biggest onboarding into crypto and Web3” to date, Blania told MIT Technology Review in an interview, addressing one of Web3’s major challenges: a relative dearth of users.

Additionally, by biometrically confirming that an individual is human, Worldcoin would solve another “very fundamental problem” in decentralized technologies, according to Blania: the risk of so-called Sybil attacks, which occur when one entity in a network creates and controls multiple fake accounts. This is particularly dangerous in decentralized networks where pseudonyms are expected. Coming up with a truly Sybil-resistant proof of personhood has thus far been difficult, and this is seen as another barrier for mass Web3 adoption.

Worldcoin has done field testing in 24 countries; (from left to right) these promotional images were taken in Sudan, Indonesia, Chile, and Kenya.

With these two solutions, Worldcoin could become “an open platform that everyone can use [for] both the proof-of-person part and the distribution part,” Blania said. Therein lies Worldcoin’s promise: if it succeeds, this protocol could become the universal authentication method for a whole new generation of the internet. If that happens, the currency itself could become far more valuable. “Investors hope that the Worldcoin project brings value to the world and, as a result, that this equity and/or these tokens will appreciate in value,” the company said in an emailed statement.

This may be why some of Silicon Valley’s biggest names, in addition to Altman, are pouring money into it; Andreessen Horowitz recently led a $100 million investment round that tripled the startup’s valuation, from an already heady $1 billion to $3 billion.

Look into the orb

By the time we spoke to Blania in March, Worldcoin had already scanned 450,000 eyes, faces, and bodies in 24 countries. Of those, 14 are developing nations, according to the World Bank. Eight are located in Africa. But the company was just getting started—its aim is to garner a billion sign-ups by 2023.

Central to Worldcoin’s distribution was the high-tech orb itself, armed with advanced cameras and sensors that not only scanned irises but took high-resolution images of “users’ body, face, and eyes, including users’ irises,” according to the company’s descriptions in a blog post. Additionally, its data consent form notes that the company also conduct “contactless doppler radar detection of your heartbeat, breathing, and other vital signs.” In response to our questions, Worldcoin said it never implemented vital sign detection techniques, and that it will remove this language from its data consent form. (As of press time, the language remains.)

The biometric information is used to generate an “IrisHash,” a code that is stored locally on the orb. The code is never shared, according to Worldcoin, but rather is used to check whether that IrisHash already exists in Worldcoin’s database. To do this, the company says, it uses a novel privacy-protecting cryptographic method known as a zero-knowledge proof. If the algorithm finds a match, this indicates that a person has already tried to sign up. If it does not, the individual has passed the uniqueness check and can continue registration with an email address, phone number, or QR code to access a Worldcoin wallet. All of this is meant to occur in seconds.

Worldcoin says that biometric information remains on the orb and is deleted once uploaded—or at least it will be one day, once the company has finished training its AI neural network to recognize irises and detect fraud. Until then, beyond vague descriptions like “personal data…sent via secure, encrypted channels,” it’s unclear how this data is being handled. “During our field-testing phase, we are collecting and securely storing more data than we will upon its completion,” the blog post states. “We will delete all the biometric data we have collected during field testing once our algorithms are fully-trained.”

In response to our questions just before this article went to press, Worldcoin said the public version of their system would soon eliminate the need for new users to share any biometric data with the company—though it hasn’t explained how this will work.

A useless IOU

But we do know how onboarding works. To get Worldcoin into the smartphones of new users, the company contracts with local ”orb operators” to manage signups for their countries or regions.

Operators apply for the job and are interviewed and approved by the Worldcoin team, though Anastasia Golovina, a company spokesperson, emphasized in an email that operators “are independent contractors, not Worldcoin employees.” As such, they work without contracts or guarantee of payment, instead receiving commission for each person’s biometric data that they collect. However, Golovina added, they must “comply with local laws and regulations, including local labor laws.”

These country-level operators receive their commission in the stablecoin Tether. Stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency whose value is pegged to a traditional currency, often the US dollar. They determine the rates they pay their subcontractors (typically in local currency), as well as the working conditions (full-time, part-time, or temporary gig work.) Both country-level and subcontracted orb operators are incentivized by commission-based payment structures to register as many people as quickly as possible.

On the other side, new users currently earn at least $15 worth of Worldcoin for submitting to the biometric scan, and $5 more when they log in to their Worldcoin wallet, though the total amount available has since changed to $25 for later recruits. Some users receive the sum all at once, for others it vests at a rate of $2.50 per week. Blania says that differences are meant to test out the most effective incentives. Either way, Worldcoin isn’t a stablecoin, and since the currency has not yet launched, the company “do[es] not yet know how many WLD tokens would be equivalent to USD $20,” it noted in a written statement.

To understand user incentives, some people were given the option to receive $20 worth of Bitcoin instead, effectively allowing them to cash out. Worldcoin said that it found its “most engaged users elected to hold on to their WLD,” though most of our interviewees said the opposite.

But with the ability to cash out ending last fall, for now the promise of $20 or $25 worth of Worldcoin amounts to an IOU from the company. Any tokens users may have in their digital wallets are, for all intents and purposes, worthless.

Taking a chance

Worldcoin’s users joined for a myriad of reasons.

“Out of curiosity” was a common refrain. Because the orb operator “seemed nice”—or happened to be their brother, cousin, or classmate—was another. Some hoped to get in early on what could become the next Bitcoin. Others had lost jobs or income during the pandemic. Some became desperate as civil war threatened to reignite around them. Most just wanted the free money—at least one only wanted to buy lunch. Many suspected it was a scam, though few could risk passing it up in case it was not.

Ruswandi fit into several of these categories. He had lost much of his work as a furniture maker during the pandemic and spent his free time trading stocks and cryptocurrencies and frequenting crypto-related message boards and exchanges.

“I was curious and thought it wouldn’t hurt to try,” he recalled, adding that the money was attractive given his reduced income.

But he quickly had doubts. Neither the company representatives on site nor the village officials could answer even basic questions about Worldcoin. After doing more research online and coming up empty, he came to conclude it was a scam. He believed the mysterious giveaway was a mass data collection effort disguised as some kind of secret, offline airdrop—a tactic in which cryptocurrency projects release free tokens to encourage adoption.

After all, many of his neighbors’ understanding of the internet was limited to the Facebook app pre-installed on their smartphones, so before prospective users were even able to receive the new currency, Worldcoin representatives “first had to help many residents in setting up emails [and] logging in to the web,” Ruswandi recalled. If it was about attracting users to a new cryptocurrency, he wondered, “why did Worldcoin target lower-income communities in the first place, instead of crypto enthusiasts or communities?”

The biometrics question

When Worldcoin made its “We’re here!” announcement last October, it encountered immediate backlash.

As NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden put it in a tweet thread, “Don’t catalogue eyeballs. Don’t use biometrics for anti-fraud. In fact, don’t use biometrics for anything. The human body is not a ticket-punch.”

MUHAMMAD FADLI

Many doubted Worldcoin’s privacy protocols, especially since the company had yet to issue a white paper or open its code for outside evaluation. “This looks like it produces a global (hash) database of people’s iris scans (for ‘fairness’), and waves away the implications by saying ‘we deleted the scans!’ Yeah, but you save the *hashes* produced by the scans. Hashes that match *future* scans,” Snowden tweeted.

There were also questions about hardware security. Jeremy Clark, an associate professor at the Concordia Institute for Information Systems Engineering that focuses on applied cryptography, questions the security of the orb: “The machine itself will have some security protections,” he says, “but none of that technology is perfectly secure. So it’s usually an economic question…if this project is as successful as they want it to be, then it’s going to become more profitable to try and tackle.”

Others took issue with the company’s purported focus on fairness given that 20% of the coins had already been allocated: 10% to Worldcoin’s full-time employees, and another 10% to investors, like Andreessen Horowitz.

Additionally, many in the blockchain field disagreed with the underlying premise of what Worldcoin was trying to build: creating one identity across Web3 was anathema to a movement that had turned to blockchain, decentralized finance, and DAOs (“decentralized autonomous organizations”) for the express purpose of not being known.

Others remain unconvinced that Worldcoin can actually reach everyone in the world—and instead, serves as a distraction from ongoing work to create new identity paradigms. Identity expert Kaliya Young, while declining to comment on Worldcoin specifically, says that “it’s common for companies to claim that ‘if everyone in the world was in our system, everything would be fine.’ Newsflash: everybody is not going to be in your system, so let’s move on and talk about how we solve problems” in online identity.

For Blania and his team, the criticism misses the mark. “Big parts of our team have had backgrounds in crypto…so we care about this [privacy] a lot,” he told MIT Technology Review. “I fully understand the concern,” he said, but he thinks it’s more “emotional gut reaction” than “objective criticism.” What the critics were missing, he added, was just how good Worldcoin’s protocol would be at protecting privacy once complete.

Stephanie Schuckers, the director of the Center for Identification Technology Research at Clarkson University, says that’s not outside the realm of possibility, as biometric technology has made a number of recent advances. One of the newest trends is “template security,” which uses cryptography to make a transformation of your biometric data. “When you store it, if it were stolen, it can’t be reverse-engineered back to your original biometrics,” she says.

But the reason that it has yet to be commercialized, she adds, is that cryptographic transformation often leads to “performance degradation.” Instead of matching the new biometric data to an existing biometric sample, template security matches a computer algorithm’s interpretation of the data, via some kind of hash or code, to another stored code. This adds room for error, Schucker says, making it “more difficult to match biometrics in this encrypted space,” though she adds that recent advances in template security have addressed some of those shortcomings.

Template security sounded like a possibility for what Worldcoin was doing—though Schucker cautioned that without seeing their code, or more detail beyond Worldcoin’s blog posts, it was hard to say for sure. Worldcoin has promised to open source its code, including repeating to MIT Technology Review on multiple occasions that this would occur “within the next few weeks”—since we first contacted the company in February.

Besides, the company added in a statement, “It is important to emphasize that we collect data not for the purpose of profiting from it or surveilling our users, like many other tech companies out there. Rather, our goal is to use the data for the sole purpose of developing our algorithms to minimize fraud and enhance user privacy.”

Reeling them in

Representatives of Worldcoin used a range of questionable tactics and enticements to bring in new users, according to many of the people MIT Technology Review spoke to.

When operations began in Sudan last March, the operators found it hard to “explain the concept of digital currencies to people who don’t even have emails”, according to Mohammad Ahmed Abdalbagee, one of Sudan’s four former orb operators. So instead they ran an AirPod giveaway contest to encourage registration that resulted in some 20,000 sign-ups.

At an Islamic high school in Indonesia’s West Java province, Worldcoin applied to teach a cryptocurrency workshop. The school’s student activity coordinator, Muhammad Hilham Zein, read the application and recommended it for approval on the understanding that it was “to share knowledge on crypto…not to encourage students to invest in digital currency.”

“Why did Worldcoin target lower-income communities in the first place, instead of crypto enthusiasts or communities?”

But attendees—at least one of whom was 15, which violates Worldcoin’s own terms of use—as well as our reporter’s first-hand observations tell a different story. During the 45-minute sessions, Worldcoin staff were too busy registering the dozen or so students, helping them download the app and sign up for emails, and finally scanning their biometrics, to provide information on cryptocurrency, Worldcoin itself, or how participants could give or take away consent. (Students did, at least receive their allotment of Worldcoin, which would vest weekly).

More recently, in roughly 20 villages in West Java that hosted recruitment events, many new users, like Iyus Ruswandi, were attracted by giveaways.

“It was held during the pandemic, where the government usually handed out social assistance packages,” explained Ece Mulyana, the principal of an elementary school madrasa who was informed, the night before, that his school was to be used as a Worldcoin registration site. Because the instructions came from a higher-level official—Ade Irma, the sub-district governance head, who was helping Worldcoin coordinate the village registration drives, “I couldn’t refuse the request,” Mulyana said.

Mulyana says that Irma paid him a fee of 2,000 IDR (around 14 US cents, at the time of writing) for each person successfully scanned. Mulyana estimates that 170 made the cut, for a total of 340,000 IDR (roughly $23.80, just under 10% of the average monthly pay of a government worker ).

Heni Mulyani, the sub-district leader who approved the events and Irma’s boss, said the money was provided “for coffee and cigarettes,” a euphemism for gratuities given to government officials to facilitate desired actions. She said none of the money paid went towards site rental—but, she added, “we assure you it’s not coming from the village fund or budget.”

MUHAMMAD FADLI

Instead, the money came from a company called PT Sandina Abadi Nusantara, cofounded by a man named Muhammad Reza Ichsan, who happens to be Worldcoin’s “best-performing operator” (according to Worldcoin’s launch blog post), and his mother. The company was the legal entity through which Worldcoin Indonesia conducted its activities; it was Ichsan’s mother’s job to reach out to local government officials to coordinate recruitment.

Ichsan has told MIT Technology Review that “we don’t pay the village, but we have an operational fund for people who helped us assemble the public in the field.”

Even if Mulyani had not misused village funds, these gratuities are—with rare exceptions— illegal under Indonesia’s anti-corruption and anti-bribery laws, with potential criminal penalties for both the giver and receiver.

In response to questions about payments to village officials, Worldcoin representatives said they were unaware of the incident, called it “isolated,” and that they have launched an investigation to learn more. While they could not yet draw conclusions, Golovina wrote, “It appears possible that some or all of these payments may have been for bona fide operating expenses, for example, fees required to set up operations in a school or other facility, or to pay for permits or licenses required to operate in certain locations.” This stands in contradiction to both the official’s and their orb operator’s descriptions.

Worldcoin also called the other examples we put to them, including the AirPod giveaway in Sudan and the deception of school officials in Indonesia “independent and isolated efforts by local Orb Operators,” and added that “we are wholly focused on incentivizing Operators to sign up engaged users who are excited about using Worldcoin.”

For their part, villagers were not told that at least some of their officials were being paid to promote Worldcoin; in fact, many thought the event was run by the government itself, as Mulyana, the school principal, recalled. “We have to explain to them that it was not a government program,” he said—that “Worldcoin is a foreign company who came and needed help from the village staff.”

Some villagers now doubt that they will receive any money at all now that late January, the time when they were told Worldcoin representatives would return to the village to hand out funds, has come and gone. Nor has the ability to trade Worldcoin from the wallet appeared, for those digitally savvy enough to navigate the app.

Operating blind

The mixed messages and misinformation weren’t necessarily intentional. The orb operators we spoke to often mentioned how little information they received from the Worldcoin representatives who recruited them, even as they were made acutely aware that their payment was tied to the number of people they could sign up. (Worldcoin said that it provides its country-level orb operators with a code of conduct, which sub-operators must also abide by, and that it is moving away from commissions based on number of sign-ups.)

Bryan Mtembei was one such operator. A civil engineer who recently graduated from college in Nakuru, Kenya’s fourth-largest city, Mtembei freelanced for Worldcoin after he was scanned on campus last September.

He wishes that he had received “a brief training or basics about Worldcoin.” Instead the only instruction he got was to “bring more people in to get yourself more money,” he said. “The rest was up to my social marketing skills.”

So he did his best to answer new users’ questions, with the most frequent being about privacy: Mtembei estimates that roughly 40% of the individuals he approached had concerns about sharing their biometric data. When he initially expressed similar concerns, he was assured by a representative that all his questions were addressed in the Worldcoin “white paper.” No such document exists. According to the company, this is by design—people would be unlikely to read “a long, highly technical academic-style paper,” it said, and its shorter blog posts could be thought of as white papers. Ultimately, Mtembei’s need for money overrode his concerns; he says that he signed up between 150 and 200 people, at 50 KS (44 US cents) per scan.

BRIAN OTIENO

And he wasn’t alone. Willis Okach, a college student in Nairobi recruited, like Mtembei, to become an orb operator after his own scan, also got involved because of the money. “You don’t have any and someone is offering you some,” he explained, adding that he thinks Worldcoin “feels that students don’t have a lot of money so they will sign up.” For his two days of work, Okach signed up 50 people and earned 100 KS (USD 0.88) for each set of biometric data that he brought in.

According to Golovina, the Worldcoin spokesperson, “all users who sign up during field testing are provided full disclosure about what is being collected and how that data is used and are required to provide their consent before they’re allowed to sign up. Any individual who does consent to our collection and use of their biometric data may revoke their consent at any time and this data will be deleted.”

But of the people we interviewed, none were explicitly told—or, in the case of orb operators, told others—that they were “test users,” that photographs and videos of their faces, and 3D body maps were captured and being used to train the orb’s “anti-fraud algorithm” to “differentiate between people,” that their data was treated differently from the way others’ would be handled later, or that they could ask for their data to be deleted.

Ángel Rodriguez, a security guard for the Santiago Metro in Chile, recalled checking a box in the Worldcoin app agreeing to the terms of service, but recalled the instructions being in English, a language that he does not read. In addition, the app, with its link to the data consent forms, was not available until “late 2021,” according to Worldcoin, at which point, field testing had been going on for at least a year.

Sometimes, new users were asked to provide additional personal data, which Worldcoin claims it never requests. Almost all of the people we spoke to were asked to provide email addresses to log into their wallets (even after Worldcoin introduced a QR code for sign-ins). Some were asked for phone numbers as well.

Golovina has denied in multiple email statements that emails or phone numbers were required for sign-up, though “we do make certain features available to users who choose to provide their phone number or email address, like the ability to send and receive Worldcoin. But things like this will always be optional.” Worldcoin did not explain what else users could do with the token without the ability to send or receive it.

In Nairobi, meanwhile, several students said that orb operators took a photo of their national ID cards to confirm, as Okach recalled, that he was “not…a robot.” Worldcoin said that it has never requested national identification documents from users, though they do request it from their orb operators.

When we shared these comments with interviewees, they did not recognize their own experiences. Mtembei emphasized that personal details were never optional, and there was no way to sign up at his orb without both email and phone. “That CEO is lying,” he said (mistakenly attributing Golovina’s statement to Blania.)

Mohammad Ahmed Abdalbagee, one of the four orb operators hired in Sudan, added that it was his team’s efforts that convinced Worldcoin to add phone numbers as a sign-in method in the first place. “Before they started in Sudan, they used the email as the main identifier, but we told them that this wouldn’t work in Sudan. Many college students don’t even have emails, they use their phones to register in social media,” he said.

Crypto-colonialism

Researchers that study the tech sector’s relationship with the global south were concerned—but not surprised—by Worldcoin’s behavior.

“It’s a race to see who gets the most data in this AI-driven economy,” says Payal Arora, a digital anthropologist and author of The Next Billion Users: Digital Life Beyond the West. Stronger data protection laws in Europe and the United States mean that the most ambitious entrepreneurs in those regions can’t get all the training data that they need from their own populations, she says, so they have to look to the developing world.

In fact, according to its launch blog post, Worldcoin is unavailable in either the United States or China due to regulatory constraints, while Bloomberg reported that it has also shut down field tests in other countries, including Turkey and Sudan, for similar reasons. Worldcoin has, however, signed up a number of users in the US at demos held at cryptocurrency conferences, though the company does not consider its US activities to be a form of field testing.

It’s just cheaper and easier to run this kind of data collection operation in places where people have little money and few legal protections.

Pete Howson, a senior lecturer at Northumbria University who researches cryptocurrency in international development, categorizes Worldcoin’s actions as a sort of crypto-colonialism, where “blockchain and cryptocurrency experiments are being imposed on vulnerable communities essentially because…these people can’t push back,” he told MIT Technology Review in an email.

What makes the crypto version even more harmful than other forms of data colonialism is that decentralization, the core tenet of blockchain, makes for “very limited accountability…when things go wrong,” Howson explained. “You’ll often hear this phrase ‘Do Your Own Research’, or DYOR, because these guys don’t care much for rules and regulations.”

But inequities in information and internet access make that “do your own research” ethos all but impractical for many people in developing regions. Similarly, huge economic disparity means that in Kenya, say, the promise of just under half a US dollar could be a compelling incentive for someone to give up their biometric data, whereas in Norway or the US, such an offer wouldn’t go far.

Simply put, it’s just cheaper and easier to run this kind of data collection operation in places where people have little money and few legal protections.

Data lapses and policy holes

Although much of Worldcoin’s field testing has been happening in developing countries, the company stressed that it is also active in developed countries, including several in Europe. “Worldcoin has always tried to conduct field tests in a sample of countries around the globe that would be representative of the world as a whole,” the company told us.

This presents its own challenges. In collecting, controlling, and processing the data of EU-defined “data subjects”—that is, any person within the European Union, including citizens, residents, and potentially visitors whose data is being collected—Worldcoin is subject to the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Enacted in 2018, the GDPR requires that data subjects be fully informed about why their data is collected, how it will be used, who will be processing it, where it will be transferred, how they can erase it, and how they can stop its processing. Failing to sufficiently safeguard data can lead to fines of up to 5% of global revenue or 20 million euros, depending on the severity of the infraction. Further, GDPR was written to be extraterritorial in scope, meaning that a company registered in Delaware and headquartered in San Francisco, like Worldcoin, is not exempt.

That is, however, exactly what Worldcoin has claimed in its data consent form, which—until MIT Technology Review submitted its list of questions—asked users to accept the following statements:

- “we [Worldcoin] voluntarily comply with the GDPR as a matter of policy”

- “we have not adopted a board-approved data privacy and security policy describing the means and the methods by which we plan to protect your Data to meet the standards prevalent in the GDPR”

- “there is a possibility that our policies and procedures will not be sufficient to meet GDPR requirements”

- “it may be more difficult to assert your privacy rights in court in the United States if we do not comply”

This policy tries to create “carve-outs,” says Marietje Schaake, the international policy director at Stanford University’s Cyber Policy Center and a former Member of the European Parliament, who reviewed the document. Exceptions, she adds, are not possible under the GDPR—and besides, the fact that Worldcoin has a German subsidiary already subjects it to the GDPR.

“As an EU citizen, you have the right to challenge it,” Schaake says, referring to any potential violation. Those challenges would be reviewed by European data protection authorities and eventually argued in European courts rather than American ones, as Worldcoin’s policy suggests.

Worldcoin said that it is fully compliant with the GDPR, and has registered with the Bavarian Data Protection Authority. It added that it employs a data protection officer, and that it has conducted a data privacy impact assessment—though it has declined to make either the officer or the assessment available for public scrutiny. Worldcoin added that the statements in their consent policy “were previously included in an abundance of caution…They no longer appear in the latest version of our Data Consent Form.” As of publication, however, the language still remains online.

For Aida Ponce del Castillo, a researcher at the European Union Trade Institute, who studies regulations for emerging technology and serves as her organization’s data protection officer, this lack of transparency is unjustified. “DPIA are not confidential business information,” she told MIT Technology Review—and while publication is not mandatory, she pointed to European Commission recommendations that companies “consider publishing at least parts, such as a summary or a conclusion.”

The Bavarian Data Protection Authority has yet to respond to MIT Technology Review’s request to confirm the company’s registration.

“That’s manipulation”

Beyond the ethical questions, though, lie more practical ones, like: how well does Worldcoin actually work?

For some test users and orb operators on the ground the answer has been, not well at all.

Sometimes, this was due to issues with the orb. In Sudan, local orb operator Abdalbargee says that it would take as many as six attempts for the orb to recognize someone’s face. “Actually it took my friend an entire week for the device to recognize his iris,” he adds.

Orbs were also prone to malfunctions, slowing down recruitment processes and requiring repair in Germany. When Buzzfeed News found similar orb malfunctions in a recent investigation, Worldcoin used language that it has repeated with us: calling one particularly egregious case an “isolated outlier.”

Meanwhile, the transition from a web-based wallet to an app-based wallet has caused a number of users to appear to lose either their entire accounts or all of their coins. For others, the app has proved buggy, draining battery life or leading them into in a spiral of loading and reloading.

Rodriguez, the Chilean security guard, has been trying to resolve his wallet issues since shortly after he was scanned. After signing up in February, and being asked to input his email, phone number, and use a QR code, the app was creating such performance issues for his phone that he deleted it entirely. When he tried to re-download the app, he found that his username no longer existed.

To fix it, he was told by a local orb operator, he would have to find the orb and re-scan his biometric data. But if Worldcoin works as the company claims, re-scanning his iris would simply result in the orb linking his iris with his old iris hash. In other words—and as Worldcoin has subsequently confirmed— there’s no way to recover an account once it’s lost.

Then there are the instances of identity spoofing that the orb has been unable to detect. In mid-2021, one businessman in Indonesia was able to register and access the wallets of over 200 users after they had been scanned and verified as human, and transfer out their contents—held in Bitcoin at the time. Worldcoin says that this occurred when the wallet was still accessible via a web log-in, rather than a mobile app, and that “since transitioning…we have not detected this type of fraud.”

Meanwhile, those who fear that the whole thing may have been a scam want to know what they’ve lost. “50 KS is not enough to give an eyeball away,” says Okach, the university student in Nairobi that spent a weekend recruiting others to Worldcoin. “That’s manipulation, taking advantage of students without clear clarification about what it is they are doing or what they want.”

Forget all those people

When we began reporting this story we noticed that three of the five countries initially cited as case studies for successful field testing—Indonesia, Sudan, and Kenya—were classified as low or lower-middle income by the World Bank. The power and economic differentials seemed ethically fraught, so we began digging.

We wanted to know: what was it like to serve as an early user in this global crypto experiment? What did the participants actually understand—or what were they told—about cryptocurrency, Worldcoin, and the ramifications of giving up their biometric data? Did they provide informed consent—and what would that even look like in this context? And, ultimately—sharing the same question voiced by many of our interviewees—what were the iris scans really for?

Left to right: Ruswandi’s neighbors Sadili, Solihin (a community leader), and Eli were among the 170 villagers scanned.

In the end, it was something that Blania said, in passing, during our interview in early March that helped us finally begin to understand Worldcoin.

“We will let privacy experts take our systems apart, over and over, before we actually deploy them on a large scale,” he said, responding to a question about the privacy-related backlash last fall.

Blania had just shared how his company had onboarded 450,000 individuals to Worldcoin—meaning that its orbs had scanned 450,000 sets of eyes, faces, and bodies, stored all that data to train its neural network. The company recognized this data collection as problematic and aimed to stop doing it. Yet it did not provide these early users the same privacy protections. We were perplexed by this seeming contradiction: were we the ones lacking in vision and ability to see the bigger picture? After all, compared with the company’s stated goal of signing up one billion users, perhaps 450,000 is small.

But each one of those 450,000 is a person, with his or her own hopes, lives, and rights that have nothing to do with the ambitions of a Silicon Valley startup.

Speaking to Blania clarified something we had struggled to make sense of: how a company could speak so passionately about its privacy-protecting protocols while clearly violating the privacy of so many. Our interview helped us see that, for Worldcoin, these legions of test users were not, for the most part, its intended end users. Rather, their eyes, bodies, and very patterns of life were simply grist for Worldcoin’s neural networks. The lower-level orb operators, meanwhile, were paid pennies to feed the algorithm, often grappling privately with their own moral qualms. The massive effort to teach Worldcoin’s AI to recognize who or what was human was, ironically, dehumanizing to those involved.

When we put seven pages of reporting findings and questions to Worldcoin, the company’s response was that nearly everything negative that we uncovered were simply “isolated incident[s]” that ultimately wouldn’t matter anyway, because the next (public) iteration would be better. “We believe that rights to privacy and anonymity are fundamental, which is why, within the next few weeks, everyone signing up for Worldcoin will be able to do so without sharing any of their biometric data with us,” the company wrote. That nearly half a million people had already been subject to their testing seemed of little import.

Rather, what really matters are the results: that Worldcoin will have an attractive user number to bolster its sales pitch as Web3’s preferred identity solution. And whenever the real, monetizable products—whether it’s the orbs, the Web3 passport, the currency itself, or all of the above—launch for its intended users, everything will be ready, with no messy signs of the labor or the human body parts behind it.

Additional reporting by Lujain Alsedeg and Antoaneta Roussi