No one can find the animal that gave people covid-19

A wild-animal trader who caught a strange new virus from a frozen pangolin. A lab worker studying bat viruses who slipped up and sniffed the air under her biosafety hood. A man who suddenly fell ill after collecting bat guano from a cave to use for fertilizer.

Were any of these scenarios what touched off the covid-19 pandemic?

That is the question facing a joint international research team appointed by China and the World Health Organization that is now searching for the source of covid-19. What the researchers know so far is that a coronavirus very similar to some found in horseshoe bats made the jump into humans, appeared in the Chinese city of Wuhan by December 2019, and from there ignited the biggest health calamity of the 21st century.

We also know they haven’t found the critical detail: if it was in fact a virus with an origin in horseshoe bats, how did it make its way into humans from creatures living hundreds of miles away in remote caves?

An 300-page report from the group is expected soon. It is intended to summarize everything that’s known about the early days of the outbreak and the Chinese effort to locate its source, and it’s likely to forward a favored hypothesis: that the virus, SARS-CoV-2, reached humans from bats via “an intermediate host species,” such as a wild animal sold as a food delicacy in Wuhan’s markets.

That’s a reasonable theory: other bat coronaviruses have jumped to humans the same way. In fact, such a “spillover event” was the origin of SARS, a similar coronavirus that panicked the world in 2003 when it spread out of southern China and sickened 8,000 people. With SARS, researchers tested caged market animals and quickly found a nearly identical virus in Himalayan palm civet cats and racoon dogs, which are also eaten locally.

This time, though, the intermediate-host hypothesis has one big problem. More than a year after covid-19 began, no food animal has been identified as a reservoir for the pandemic virus. That’s despite efforts by China to test tens of thousands of animals, including pigs, goats, and geese, according to Liang Wannian, who leads the Chinese side of the research team. No one has found a “direct progenitor” of the virus, he says, and therefore the pandemic “remains an unsolved mystery.”

Politics at play

It’s important to know how the pandemic started, because after killing more than 2.5 million people and causing trillions of dollars in economic losses, it’s not over. The virus may well be establishing itself in new species, like wild rabbits or even house pets. Learning how the pandemic began could help health experts avert the next one, or at least react more swiftly.

We know that the payoffs of origin hunting are real. After the 2003 SARS outbreak, researchers started building up a big knowledge base about this type of virus. That knowledge is what turbocharged the development process for vaccines against the new coronavirus in early 2020. One Chinese company, Sinovac Biotech, actually dusted off a 16-year-old vaccine design it had shelved after the SARS outbreak was contained.

But some fear that all the research into bat viruses may have backfired in a shocking way. These people point to a striking coincidence: the Wuhan Institute of Virology, the world epicenter of research on dangerous SARS-like bat coronaviruses, to which SARS-CoV-2 is related, is in the same city where the pandemic first broke loose. They suspect that covid-19 is the result of an accidental leak from the lab.

“It’s possible they caused a pandemic they were intending to prevent,” says Matthew Pottinger, a former deputy national security advisor at the White House. Pottinger, who was a journalist working in China during the original SARS outbreak, believes it is “very much possible that it did emerge from the laboratory” and that the Chinese government is loath to admit it. Pottinger says that is why Beijing’s joint research with the WHO “is completely insufficient as far as a credible investigation.”

What’s certain is that the research to find the pandemic’s cause is politically charged because of the way it could assign blame for the global disaster. Since last spring, the hunt for the origin of what former president Donald Trump called the “China virus” has been in the crossfire of US-China trade battles and American charges that the WHO has played patsy for Beijing. China, meanwhile, has sought opportunities to spread responsibility. Chinese researchers have found ways to suggest that covid-19 started in Italy or that it arrived in Wuhan on frozen meat. This “cold chain” theory could cast the origin, and the blame, far beyond China’s borders.

One price of the politically charged atmosphere is that an entire year passed before WHO origins investigators got on the ground, arriving in January for a closely chaperoned trip. “It’s a year later, so you have to ask what took so long,’” says Alan Schnur, a former WHO epidemiologist in China who helped track the original SARS outbreak. During that year, memories faded and so did antibodies, possibly erasing key clues.

Early clues

The joint investigation team consists of 15 members appointed by the WHO alongside a Chinese contingent, with veterinarians as well as experts in epidemiology and food safety. “There is a popular perception of a group of Sherlock Holmeses going in with magnifying glasses and swabs,” John Watson, a senior British epidemiologist on the mission said during a webinar organized by Chatham House in March. “But that is not how it was set up.”

Instead, Beijing and the WHO agreed last summer to a series of scientific studies that were carried out in China. When the foreign members visited Wuhan in January, it was to help in a joint assessment of the evidence China had found, not to scour the city for new facts. “There was no freedom at all to wander around,” Watson has said.

According to Peter Ben Embarek, a WHO food safety official, the team’s two primary aims were to determine exactly when the outbreak started and then to learn how it emerged and jumped into the human population. To do that, he says, they relied on three types of data: genetic sequences of the virus, tests on animals, and epidemiological research into the earliest cases.

The reason finding the very first people with covid-19 is important is it would let disease sleuths look for shared factors, like jobs or habits. Did they all shop in the same stores? Were they recent travelers from out of town, or perhaps family members of laboratory scientists?

In the original SARS, it quickly became clear that chefs and people handling animals were the first cases. More of them had antibodies to the virus, too. That demonstrated a connection to food animals, which was quickly confirmed when a team from Hong Kong found an almost identical virus in civets held in market cages.

What scientists back then didn’t know was the ultimate origin of the germ, which they figured out in the following years. First, they discovered that SARS-like viruses make their natural home in horseshoe bats. And finally, in 2013, they found a virus that not only was very similar but was also capable of infecting humans. Shi Zhengli, the chief bat virus researcher at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, who was at the center of that work, called it the “missing link” in the hunt for the origin of SARS.

The hunt this time is fundamentally different. A likely origin for covid-19 is already known: it’s very close to known bat viruses. Even before the outbreak started, the Wuhan Institute had studied one whose genetic code is 96% identical to SARS-CoV-2. That’s as good a match as the “missing link” found for the original SARS.

That means the burning question now isn’t so much the deep origin of the virus as how a such a pathogen would have ended up in the city of Wuhan.

A first step was to double-check that the outbreak really did start in Wuhan, not elsewhere. China undertook a fairly vast effort to see if covid-19 could have been spreading, unseen, any earlier than December 2019. Chinese researchers checked records of more than 200 hospitals around the country for suspicious pneumonias, tracked how much cough syrup pharmacies had sold, and tested 4,500 biospecimens stored before the outbreak, including blood samples that could be screened for antibodies. The WHO team says it even interviewed the office worker who, on December 8, 2019, became the first recognized covid-19 case in China.

So far, there is no evidence the outbreak went undetected before the Wuhan cases. Genetic evidence also narrows the chance that the virus was spreading earlier, or anywhere else. Because of how the germ has accumulated mutations with time, it’s possible to estimate when it first started spreading between people. That data, too, points to a start date of late 2019.

About half the early cases, in December, had a link to the Huanan Wholesale Seafood Market, a maze of stalls selling frozen fish and some wild animals. That’s why animal markets are under suspicion. But the case is not airtight. The genetic evidence indicates that these cases are a branch of the early outbreak—that the market was a place where its spread was amplified, but not necessarily the starting point.

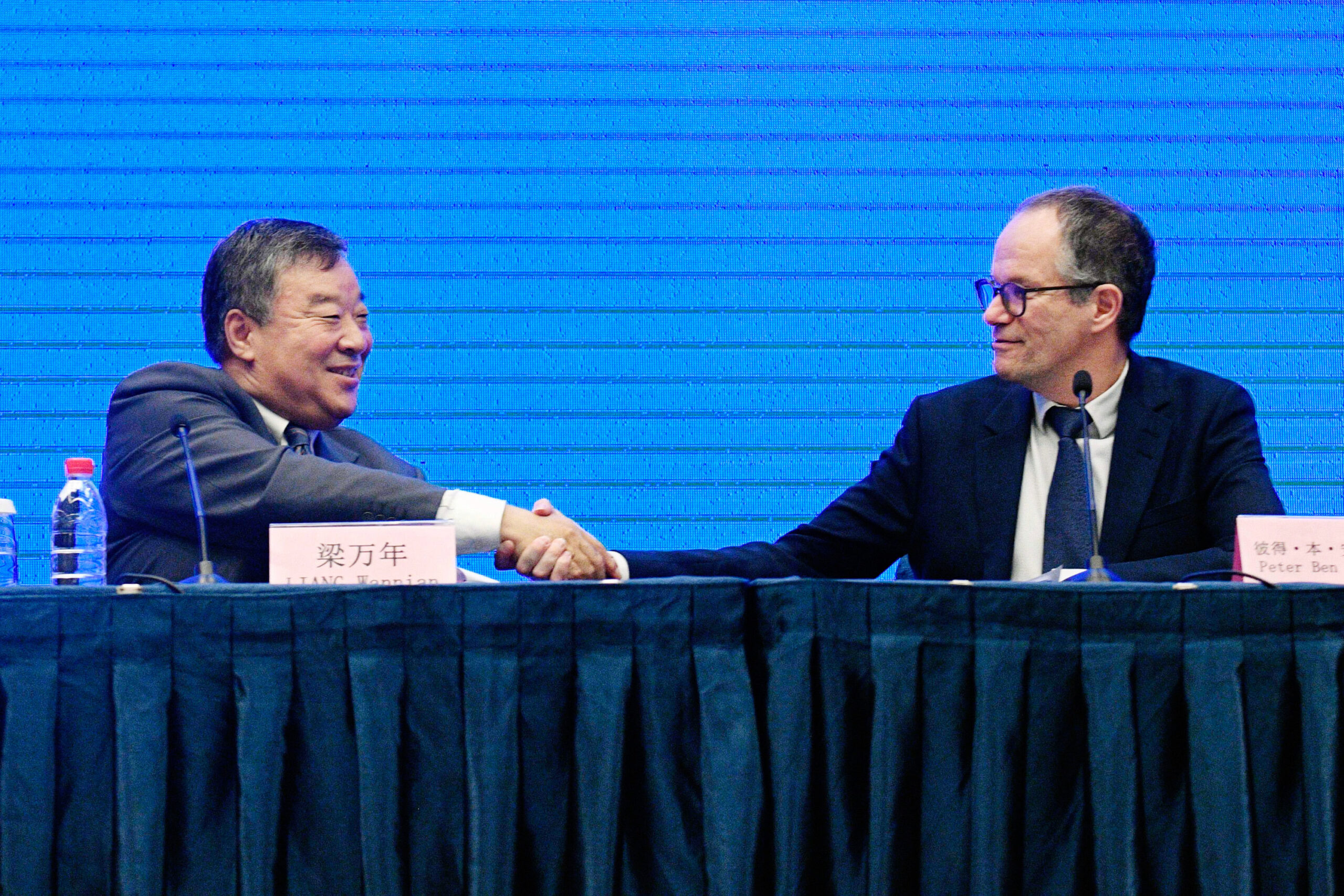

“The picture we see is a classical picture of an emerging outbreak, starting with a few sporadic cases, then seeing it spread in clusters, including in the Huanan market,” Ben Embarek said during a three-hour February press conference in Wuhan where the joint team reviewed its findings.

Ranking hypotheses

That leaves the question of how, and where, the virus jumped to humans. During the same press conference, Ben Embarek and Liang, the leaders of the WHO-China team, laid out what they called four main hypotheses and ranked them, from least to most likely.

The first was that someone became directly infected by a bat or its guano. Because of how these viruses can attach to receptors on human cells, direct infection is a possibility. But direct transmission isn’t favored as the cause of the current pandemic. That’s because the bats harboring SARS-like viruses live many hundreds of miles from Wuhan. “Since Wuhan is not a city or environment close to these bats’ environment, a direct jump from bats is not very likely,” Ben Embarek said during the press event.

The researchers went on to dismiss the lab accident theory as “extremely unlikely,” saying they had agreed not to pursue it any further. Their reasoning was fairly simple: Chinese scientists at several Wuhan labs told them they had never seen the virus before and hadn’t worked on it. “There could be a leak of a virus, but it should be a known or existing virus,” Liang reasoned, according to a translator. “If it doesn’t exist, there will be no way that this virus would be leaked.”

That argument is not foolproof. Local labs were in the business of retrieving samples from bat caves and bringing them to Wuhan for study. That means researchers could have come into contact with unfamiliar viruses. Nor have the labs been entirely forthcoming about what viruses they do know about. The Wuhan Institute of Virology possesses gene information about similar viruses that it has not released publicly. Other information disappeared from view when the institute took a database offline in late 2019, just before the outbreak started.

One problem with the lab leak theory is that it presumes the Chinese are lying or hiding facts, a position incompatible with a joint scientific effort. This may have been why the WHO team, for instance, never asked to see the offline database. Peter Daszak, president of the EcoHealth Alliance, which collaborated with the Wuhan lab for many years and funded some of its work, says there is “no evidence” whatsoever to back the lab theory. “If you just firmly believe [that] what we hear from our Chinese colleagues over there in the labs is not going to be true, we will never be able to rule it out,” he said of the lab theory. “That is the problem. In its essence, that theory is not a conspiracy theory. But people have put it forward as such, saying the Chinese side conspired to cover up evidence.”

To those who believe a lab accident is likely, including Jamie Metzl, a technology and national security fellow at the Atlantic Council, the WHO team isn’t set up to carry out the sort of forensic probe he believes is necessary. “Everyone on earth is a stakeholder in this,” he says. “It’s crazy that a year into this, there is no full investigation into the origins of the pandemic.” In February, Metzl published a statement in which he said he was “appalled” by the investigators’ quick rebuttal of the lab hypothesis and called for Daszak to be removed from the team. Several days later, the WHO director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, appeared to rebuke the origins team in a speech in which he said, “I want to clarify that all hypotheses remain open and require further study.”

The scenario the WHO-China team said it considers most probable is the “intermediary” theory, in which a bat virus infected another wild animal that was then caught or farmed for food. The intermediary theory does have the strongest precedents. Not only is there the case of SARS, but in 2012 researchers discovered Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), a deadly lung infection caused by another coronavirus, and quickly traced it to dromedary camels.

The trouble with this hypothesis is that Chinese researchers have not succeeded in finding a “direct progenitor” of this virus in any animal they’ve looked at. Liang said China had tested 50,000 animal specimens, including 1,100 bats in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located. But no luck: a matching virus still hasn’t been found.

The Chinese team appears to strongly favor a twist on the intermediate-animal idea: that the virus could have reached Wuhan on a frozen food shipment that included a frozen wild animal. This “cold chain” hypothesis may have appeal because it would mean the virus came from thousands of miles away, even outside China. “We think that is a valid option,” says Marion Koopmans, a Dutch virologist who traveled with the group. She said China had tested 1.5 million frozen samples and found the virus 30 times. “That may not be surprising in the middle of an outbreak, when many people are handling these products,” Koopmans says. “But the WHO did request studies, spiked the virus onto fish, froze and thawed it, and could culture the virus. So it’s possible. You cannot rule it out.”

Blame game

The WHO-China team, in its eventual report, is expected to suggest further research that needs to be carried out. This is one reason the report matters; it may determine which questions get asked and which don’t.

There is likely to be a larger effort to trace the wild-animal trade, including supply chains of frozen products. In addition to animal evidence, Ben Embarek also said China should make a greater effort to locate people who were infected by covid-19 early on, but perhaps were asymptomatic or didn’t get tested. That could be done by hunting through samples in blood banks, using newer, more sensitive technology to locate antibodies. “We need to keep looking for material that could give insight into the early days of the events,” Ben Embarek said. As well, the report is likely to call for the creation of a master database that includes all the data collected so far.

Ultimately, in seeking the cause of the covid-19 disaster, we don’t just want to know what happened. We’re also looking for something—or someone—to blame. And each hypothesis points to a different culprit. To ecologists, the lesson of the pandemic is nearly a foregone conclusion: humans should stop encroaching on wild areas. “We have come to recognize how this kind of investigation is not just about illness in humans—nor indeed just about an interface between humans and animals—but feeds into an altogether wider discussion about how we use the world,” says John Watson, the British epidemiologist.

The Chinese authorities, meanwhile, are already taking action on the intermediary theory by putting responsibility on wild-animal farmers and traders. Last February, according to NPR, China’s legislature started taking steps to “uproot the pernicious habit of eating wild animals.” At the behest of President Xi Jinping, they have already banned the hunting, trade, and consumption of a large number of “terrestrial wild animals,” a step never fully implemented after the original SARS outbreak. According to a report in Nature, the Chinese government has already closed 12,000 businesses, purged a million websites with information about wildlife trading, and banned the farming of bamboo rats and civets, among other species.

Then there is the chance covid-19 is the result of a laboratory accident. If that’s true, it would bring the sharpest consequences, especially for scientists like those in charge of finding the virus’s origin. If the pandemic was caused by ambitious, high-tech research on dangerous germs, it would mean China’s fast rise as a biotech powerhouse is a threat to the globe. It would mean this type of science should be severely restricted, or even banned, in China and everywhere else. More than any other hypothesis, a government-sponsored technology program run amok—along with early efforts to conceal news of the outbreak—would establish a case for retribution. “If this is a man-made catastrophe,” says Miles Yu, an analyst with the conservative Hudson Institute, “I think the world should seek reparations.”

According to some former virus chasers, what’s actually in the WHO-China origins report may be different from what we’ve heard so far. Schnur says the Chinese probably already know much more than we think, so the role of the team could be to find ways to push those facts into the light. It is a process he calls “part diplomacy and part epidemiology.” He believes China’s investigation was likely very thorough and that the foreign visitors may also have stronger views than they have let on so far.

As he points out, “What you say in a press conference may be different than what you put in a report once you have left the country.”